Notables

The headlines scream about war, crime, political strife, economic woes. But underlying it all — and more and more often bubbling to the top — is what future historians will likely look back and call the story of this century: Climate change.

Recognizing the importance of this pervasive phenomenon, Covering Climate Now, Columbia Journalism Review, the Solutions Journalism Network, The Guardian and The Nation last fall brought together more than 200 journalists from around the world to develop a plan for better reporting on this critical but often-sidelined topic.

A recently released synopsis of their work, Climate Blueprint for Media Transformation, offers journalists 14 tips for reporting on this critical topic.

1. Engage across beats

Climate affects everyone and everything — and climate change reporting should reflect that. Help colleagues of all ilks incorporate climate into their reporting, connecting it with audience members’ everyday concerns and real-life experiences.

2. Connect with communities

Take time to engage those affected by or featured in your reporting in a respectful way. Focus on people rather than deadlines.

3. Use images

When it comes to climate change, visuals truly are worth a thousand words. Photos and graphics can make stories personal and help clarify complex concepts.

4. Center justice

Consider culture and entrenched inequalities. Include affected individuals as expert sources and ensure they can access the results of your reporting.

5. Avoid propagating misinformation

Misinformation and disinformation abound in the climate sphere. Pay attention to who or what is behind the message. Query claims about solutions.

6. Attend to activism

Citizen action is an important part of the climate story. Treat protests as serious news. Carefully consider the choice of words you choose to describe the issue and the action.

7. Take care of yourself and colleagues

Climate change is a traumatizing topic that can harm mental health. Work to ensure that you and your newsroom have the resources needed to deal with the stress of climate reporting.

8. Consider the bigger picture

Proximate causes of harm such as fossil-fuel burning are an important part of the story, but so are entrenched systems that create and perpetuate vulnerability.

9. Connect with diverse experts

Cultivate skills for tapping scientific expertise from a variety of institutions. Scientists beyond “the usual suspects” can offer important insights.

10. Embrace the local angle

Every community and every individual has a climate story. Tell the broader story in the context of the place people live, work and play.

11. Assess impact

Check in with your audience to assess the impact of your reporting. Recognize that change is incremental and that shifts in intent and sentiment matter.

12. Team up

Collaborate with colleagues at other outlets to maximize your impact while making the most of limited resources.

13. Reach out for resources

Identify and tap funding that allows you to bring climate stories to light. Focus on topic areas and opportunity for impact for the best results.

14. Proactively include climate in coverage

To keep the drumbeat going, advocate for making climate stories a priority for your newsroom. Stay alert for potential stories. Allocate resources and cultivate relationships with experts so they’re available when needed.

“News coverage that shows the public its role and power is an essential climate solution,” the organizers noted in presenting the results of the convocation. “[W]ith climate impacts worsening fast and most governments and companies still dawdling, journalists must innovate and redouble commitments to climate storytelling.”

— October 22, 2024

How can communities prepare for the adverse conditions that climate change is bringing our way? A recent report from the Regional Plan Association, a nonprofit research organization working to enhance quality of life in the New York City area, has taken a whack at answering that question. By analyzing 54 plans that communities around the U.S. have put into place for building resilience in the face of change and adapting to changes as they occur, the group aimed to find commonalities, call out exemplary approaches and present options for other communities in the process of developing their own plans. Their conclusion: A lot is going on, but a lot more needs to happen — and soon.

The analysis, summarized in The State of Climate Adaptation Planning Today, identified and categorized more than 2,000 specific strategies to adapt to new conditions and enhance resilience in the face of change between 2015 and 2023. These strategies fell into five broad groups: natural and nature-based responses, engineered solutions, retreat and relocation, extreme heat responses, and equity and economic resilience.

Graphic courtesy of the Regional Plan Association

Most common, with 808 examples, were strategies — such as protecting wetland and planting trees — that tapped nature’s capacity to alleviate stresses caused by climate change. Approaches in this category are particularly valuable because they often can address multiple risks, such as increased heat and more destructive precipitation, at the same time. Native American communities in particular used nature-based solutions, applying traditional knowledge.

Equity and economic resilience strategies were second-most prevalent, with 734 strategies falling into this category. Specific elements here including making sure those most affected are part of planning, using non-financial criteria to set priorities, and making sure everyone impacted is included in communications. The researchers noted that not only can promoting these conditions reduce the impact of climate change, but reducing the impact of climate change can enhance equity and economic resilience.

Alleviating risks associated with elevated heat was also high on the list, with 381 related strategies. However, the report notes that far more needs to be done, given that, in the U.S., heat is the single biggest cause of mortality associated with weather.

Engineered solutions — those relying on elements of the built environment, such as dams and coastal erosion barriers — accounted for 256 of the strategies examined. These tend to cost more than nature-based solutions and focus on a single issue. They also may be less flexible with changing needs.

The planet’s most important stories — delivered to your inbox

Be the first to hear about important new environmental stories. Sign up now to receive our newsletter.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Physically moving away from risks accounted for 96 of the strategies explored. This largely were driven by governments providing financial and/or regulatory input that discourage inhabitation of unsafe areas.

The report not only lists strategies, but also provides brief descriptions of specific plans as a way to provide guidance to communities facing similar challenges. Elements common across the plans examined included demographic information, risk/vulnerability assessments, summaries of past efforts, descriptions of community member involvement, priority and goal setting, action planning, and identifying possible funding sources. Additionally, the report noted that some plans included protecting the well-being of nonhuman elements of nature as well as humans.

Overarching recommendations include collaborating across geographic boundaries and “departmental silos,” engaging those affected in developing adaptation and resilience strategies, prioritizing equity, and advancing initiatives that offer multiple benefits.

The researchers note, importantly, that the survey is of plans and not of actual progress in carrying them out.

— August 20, 2024

A comprehensive report on food waste published in March by the United Nations Environment Programme shares some sobering statistics: In 2022, people around the world wasted the equivalent of more than 1 billion meals each day. But the key take-home message is a far more encouraging one. In addition to scoping the extent of food waste, the report offers a specific strategy for reducing it and shares case studies that show the strategy really works — with benefits for people and the environment alike that far outweigh the costs.

Think Eat Save: Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste focuses on food waste at the household, food service and retail levels — including both edible and inedible parts of foods, since edibility is subjective and opportunities exist for productively using food not eaten. In-depth global research found that about 60% of that waste occurs at home, with 28% in food service and 12% at the retail level. All told, the edible fraction alone amounts to at least the equivalent of 1.3 meals per day for every person on the planet who experiences chronic hunger.

Noting that food waste squanders money, contributes to food insecurity and climate change, threatens biodiversity, and more, the report calls for concerted efforts to reduce it. It also proposes a step-by-step plan that countries or regions can take to tackle it.

The plan involves companies, trade organizations, government and nonprofits teaming up to assess the food waste problem within a specific geography or sector. Together, they would develop a plan to reduce it, implement the plan, measure results, and course correct as needed.

Also known as a “voluntary agreement,” the approach succeeds because it engages parts of the system before they become competitors so they can freely collaborate. It also makes it possible for changes in the system and in individual behavior to complement each other.

“The complex challenge of food loss and waste requires a systemic approach,” the authors write. “Collaboration can create a movement that is more than the sum of its parts.”

One example in which this approach has gained traction on food waste is the Courtauld Commitment in the UK. Begun in 2005, the initiative engaged more than 100 companies along with government to together fund and implement waste reduction. Food waste dropped by nearly a quarter between 2007 and 2018, and redistribution of food that likely otherwise would have been wasted more than tripled from 2015 to 2021.

In another example, the Consumer Goods Council for South Africa led creation of a food waste reduction partnership in 2020. Participants, including food retailers and multiple government agencies, aim to cut per capita food waste in half within a decade.

Encouragingly, the report notes that such partnerships are on the rise around the world. Other examples come from Australia, the Netherlands, Brazil and Colombia.

— August 11, 2024

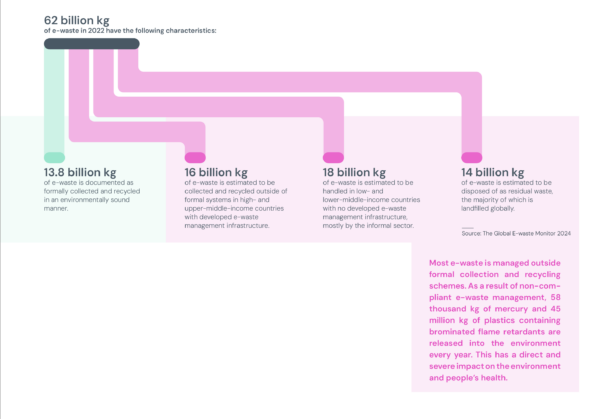

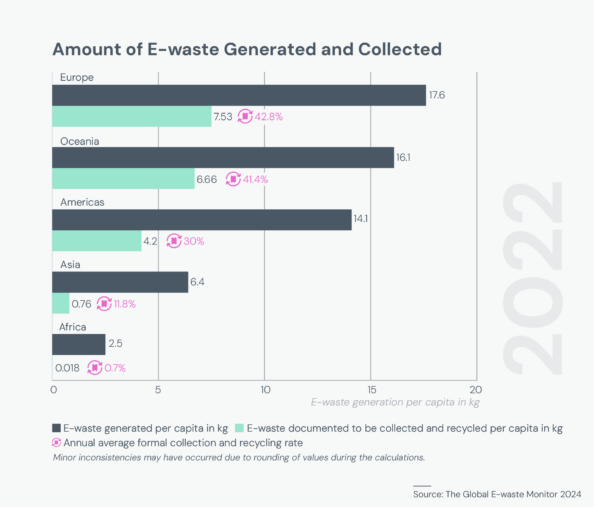

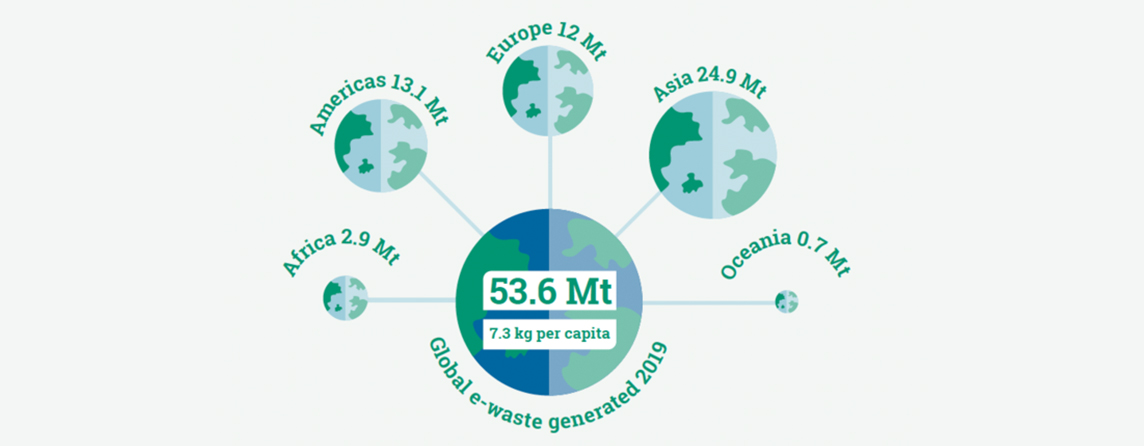

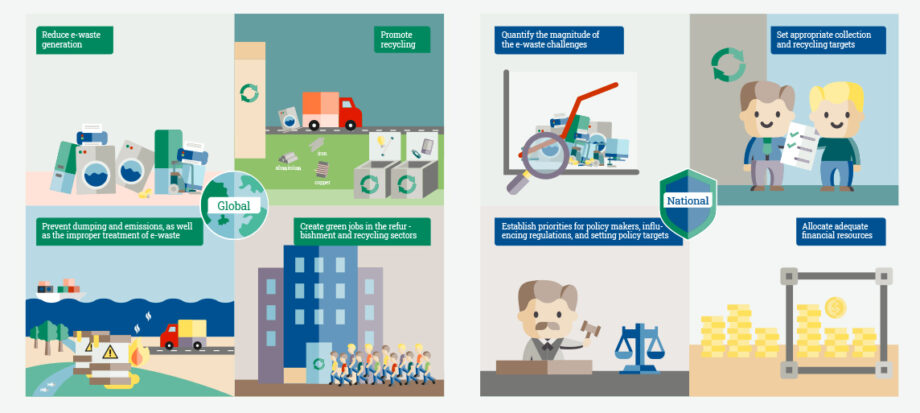

At first glance, one might consider it good news: The volume of electronic waste recycled is growing. At a closer look, the statistics are less savory: E-waste generation is accelerating five times faster.

In The Global E-Waste Monitor 2024, released in March, the United Nations Institute for Training and Research looked at current recycling rates for products ranging from phones and laptops to e-cigarettes and refrigerators. It found that e-waste generation rose from 34 million metric tons (37 million tons) in 2010 to 62 million metric tons (68 million tons) in 2022. Meanwhile, recycling only increased from 8 million metric tons (9 tons) to 13 million metric tons (14 tons) over the same period.

Current trends, such as the growth in solar photovoltaics and in the ubiquity of personal electronics, are expected to create an even greater need to deal with electronics that are perceived to have outlived their usefulness. Simply throwing them away is a problem because it adds to landfills, creates health risks, contaminates the environment, wastes valuable materials, and adds to the global greenhouse gas burden.

The low recycling rates fly in the face of the value of the materials being discarded. Electronic waste generated in 2022 alone contained some $US91 billion in metals. The problem is that extracting and recycling them currently costs even more. And fewer than half of the world’s countries have an e-waste policy, so there is little regulatory pressure to make more environmentally friendly choices.

The report notes that if recycling rates rise, eventually the value of the materials derived will exceed the cost of recycling. It projects that if 38% of electronics are recycled, the costs and value would even out. And if 60% of materials are salvaged, the economic benefit could be as high as US$38 billion per year.

So, how to boost recycling? Opportunities include improving awareness of recycling options; establishing requirements or expectations for manufacturers to take responsibility for the fate of the products they make; boosting collection capacity; providing funding and infrastructure for managing e-waste, and improving tracking and enforcement systems.

The planet’s most important stories — delivered to your inbox

Be the first to hear about important new environmental stories. Sign up now to receive our newsletter.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Best of all, though, the report says, is avoiding the production of electronic waste in the first place by making it easy to repair or refurbish used products.

— May 23, 2024

It likely is no surprise to hear that people don’t always do the good they could — even if they want to.

It likely is no surprise to hear that people don’t always do the good they could — even if they want to.

When it comes to supporting political action around climate change, that reality is particularly stark. Analysis of a series of surveys of American adults spanning three years recently found a marked gap between the willingness of respondents to take political action with respect to global warming and the extent to which they actually did act.

In a series of six surveys from March 2021 to October 2023, researchers from George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication and the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication asked thousands of respondents from a representative sample of U.S. adults whether they were willing to undertake four political actions related to global warming: sign a petition, donate funds, volunteer or contact government officials. They also asked which of these actions individuals actually took part in. Far fewer actually acted than said they would be likely to.

Looking more closely at those who expressed strong willingness to act, the study found that those for whom intention and action aligned were more likely than their non-acting counterparts and other Americans generally to talk and hear about global warming, acknowledge norms supporting climate action, and believe collective action makes a difference.

The planet’s most important stories — delivered to your inbox

Be the first to hear about important new environmental stories. Sign up now to receive our newsletter.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

What does this suggest regarding ways to close the “attitude–behavior gap”? The researchers noted that, although their study is not able to show a causal connection, it does hint at ways those seeking climate solutions might motivate the predisposed to align their actions with their predisposition. Suggestions include:

1) Ask people who are willing to take action to do so.

2) Make action easy.

3) Offer options so they can follow their personal preferences.

4) Point out how action supports their values and goals.

5) Provide examples of instances in which action has made a difference.

6) Talk about climate change.

7) Encourage others to talk about climate change.

8) Tell stories that normalize climate action.

— April 8, 2024

We’ve known for a long time that improving the built environment’s energy efficiency is good for the planet. A recent report by McKinsey Sustainability makes it clear how good it can be for business, too. And with nearly one-quarter of human-produced greenhouse gases tied to making, transporting and using building materials, and/or operating the things they’re used to build, identifying low-cost, low-carbon alternatives holds potentially huge payoffs.

We’ve known for a long time that improving the built environment’s energy efficiency is good for the planet. A recent report by McKinsey Sustainability makes it clear how good it can be for business, too. And with nearly one-quarter of human-produced greenhouse gases tied to making, transporting and using building materials, and/or operating the things they’re used to build, identifying low-cost, low-carbon alternatives holds potentially huge payoffs.

“Building value by decarbonizing the built environment,” published in June 2023, details the most promising of more than 1,000 strategies for reducing the climate impact of the built environment. For each, the researchers analyzed the potential reduction in greenhouse gas emissions; cost or savings compared with alternatives; and potential cost or savings if the technology or practice were scaled. They then sorted the best strategies according to the different categories of built environment (single-family dwellings, commercial buildings, highways, etc.) while also considering location factors such as the regulatory environment and local climate.

According to the report, many carbon-cutting strategies don’t cost any more than conventional approaches but make a big difference in climate impact. For example, the researchers found that heat pumps, which can dramatically reduce carbon emissions from home heating and cooling, already are cost-competitive with conventional heating and cooling systems.

The planet’s most important stories — delivered to your inbox

Be the first to hear about important new environmental stories. Sign up now to receive our newsletter.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

“Our analysis shows that many levers not only have proven abatement potential but are also already cost-effective,” the report notes. “In other words, companies across the built-environment ecosystem could derive value immediately from theses lower-emitting technologies and solutions.”

Not only that, but many more strategies could become cost-effective if entrepreneurs collaboratively take the opportunity to invest in developing the technologies and systems needed to bring them to scale. Specifically, the report details 17 areas that offer particularly promising opportunities for both high financial and high environmental returns on investment, clustered into eight main categories: 1) industrializing green materials production, 2) industrializing energy-efficient technology production, 3) making it easier to upgrade systems, 4) design and engineering, 5) electrifying construction, 6) reducing waste and speeding processes through offsite construction, 7) providing validation and certification of climate-friendly activities to build credibility, and 8) providing financing.

What’s standing in the way? A lack of awareness, reluctance on the part of insurers and banks to support new things, and a potential shortage of materials and labor to implement them, the report says. At the same time, it adds, innovators willing to step into untested space stand to substantially benefit by doing so at this inflection point in the industry. And the more, the better: If innovators collaborate across the board, the building sector’s climate impact could plummet 75%, according to the report.

“Decarbonizing the built environment is a significant challenge with the potential for equally significant value creation,” the authors conclude. “Despite the size of this task, there are clear actions that each player can take today to reduce the [building sector] ecosystem’s carbon footprint and capture value from new business opportunities.”

— January 18, 2024

We’ve long known that trees, parks and other green spaces can sequester carbon dioxide. But it turns out that’s just the tip of the iceberg as far as their ability to make the world a better place. When urban planners consider and work to maximize all effects on greenhouse gas emissions, the potential of these and other nature-based solutions (NBS) to contribute to climate goals multiplies many times over. In fact, if done right, NBS could help seven European cities achieve near if not total carbon-neutrality by 2030 — while also providing bountiful benefits related to resilience, biodiversity and human well-being.

We’ve long known that trees, parks and other green spaces can sequester carbon dioxide. But it turns out that’s just the tip of the iceberg as far as their ability to make the world a better place. When urban planners consider and work to maximize all effects on greenhouse gas emissions, the potential of these and other nature-based solutions (NBS) to contribute to climate goals multiplies many times over. In fact, if done right, NBS could help seven European cities achieve near if not total carbon-neutrality by 2030 — while also providing bountiful benefits related to resilience, biodiversity and human well-being.

In a paper published in Nature Climate Change in July, researchers from China, Sweden and the U.S. took a deep dive into how NBS can best contribute to the zero-carbon goals of 54 European cities. They found that green spaces and other nature-based greenhouse gas–mitigating infrastructure can do far more for climate than simply soak up carbon dioxide. By encouraging behavior changes such as walking, biking and gardening, as well as saving money and other resources, they also reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“When all benefits are considered, NBS can contribute much more to urban climate neutrality goals than mere carbon sequestration effects,” the authors write.

The planet’s most important stories — delivered to your inbox

Be the first to hear about important new environmental stories. Sign up now to receive our newsletter.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

To reach their conclusions, the researchers considered five types of NBS — green infrastructure, street trees and green pavement, green spaces and agriculture in cities, habitat remediation and preservation, and green buildings. They then assessed the potential emissions-reduction payoffs for 54 European cities by saving resources and money, reducing urban sprawl, encouraging environment-friendly behavior, improving microclimate, and storing carbon. They found the indirect climate benefits to be even greater than direct ones, with NBS able to reduce transport, residential and industrial emissions up to 25%.

Importantly, the research showed the significance of customizing the application of NBS to and within each city. For example, in Paris — where more than half of emissions come from residential areas — the best NBS approaches to apply are green infrastructure and green buildings, while in Stockholm, where the bulk of emissions are from transportation, maximum emissions reductions come from planting street trees and enhancing green spaces in cities.

“Identifying the carbon emissions reduction potential for different NBS provides valuable insight for policymakers and urban planners in prioritizing sustainable and effective solutions,” the authors conclude in a summary of their work. “By integrating NBS into city planning, and focusing especially on the indirect and behavioural effects of ecosystem services, there is an opportunity to create more climate-resilient and sustainable urban environments, improving the well-being of communities and reducing carbon emissions in the long term.”

— November 20, 2023

When people think of the impacts of climate change, they often focus on physical harm, such as loss of homes and businesses to wildfire, or illness due to floods, wildfire smoke or heat. That physical harm, however, can easily lead to financial devastation. And, as a new report from the U.S. Department of Treasury shows, this is particularly true for those living in vulnerable areas or who are already teetering on the edge of financial difficulty. Fortunately, the report also offers specific advice on how to prepare for and minimize the economic harm climate change can leverage at a personal level.

When people think of the impacts of climate change, they often focus on physical harm, such as loss of homes and businesses to wildfire, or illness due to floods, wildfire smoke or heat. That physical harm, however, can easily lead to financial devastation. And, as a new report from the U.S. Department of Treasury shows, this is particularly true for those living in vulnerable areas or who are already teetering on the edge of financial difficulty. Fortunately, the report also offers specific advice on how to prepare for and minimize the economic harm climate change can leverage at a personal level.

“The Impact of Climate Change on American Household Finances,” published earlier this month, describes the multiple financial threats that extreme heat, wildfire and floods pose, ranging from job loss, to increased energy costs, to reduced ability to afford or even qualify for insurance.

In addition to listing potential impacts, the report identifies parts of the country that are most likely to experience three primary climate change consequences: floods, wildfires and extreme heat. And it identifies and maps the location of certain populations, such as those with low income, historically marginalized groups, elders and the disabled, that are most likely to be on the edge financially and therefore particularly at risk. Overlaying the two analyses reveals three hot spots where high risk and high vulnerability converge: Appalachia, the Mississippi Delta region and states that border Mexico..

The report offers concrete advice for such communities, as well as policymakers and individuals, about ways to minimize the risk of going over the financial edge as climate change increases the frequency and impact of disasters.

First is simply becoming more aware of the many ways in which climate change can create financial stress. Second, communities can shore up infrastructure such as stormwater management systems and heat shelters, while local, state, and federal governments can boost financial resilience through initiatives such as offering emergency help and financial education. Individuals, for their part, can boost their resilience with proactive moves such as improving their homes’ energy efficiency. In addition, they can make sure they are adequately insured, adopt online bill payment and direct deposit of paychecks, and take other measures that will help them roll with the punches when they come along.

“Alongside risks to the physical environment and health, climate change already imposes substantial financial costs on communities across the United States,” the report notes. “Taken together, the findings in this report are intended to build recognition of the present and future financial challenges that households face from climate change, and opportunities and strategies for promoting social and economic resilience.” — October 18, 2023

Planting trees is one of the best things we can do to not only add beauty to our surroundings but also sequester carbon, support biodiversity and provide numerous other benefits to people and nature alike.

But which trees, where? Getting the answer to that question right plays a big role in the extent to which trees add value to the landscape and its nonhuman and human inhabitants. According to the 10 golden rules for large-scale tree planting, it’s important to choose trees species appropriate for the location in question, plant a variety rather than create a monoculture, make accommodations for a changing environment, and take the needs and interests of local people into consideration.

With tens of thousands of tree species to choose from worldwide, translating those recommendations into a detailed planting plan for a specific location can be a big challenge. But new work by researchers from Kenya, Denmark and the UK is simplifying the task. The international team recently launched an app called GlobalUsefulNativeTrees (GlobUNT) that provides customizable guidance for planning tree plantings to meet multiple benefits.

The planet’s most important stories — delivered to your inbox

Be the first to hear about important new environmental stories. Sign up now to receive our newsletter.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

The researchers created GlobUNT by combining data on some 14,000 tree species and growing conditions in 242 countries and territories with information on how the various species meet 10 use categories: animal food, environmental uses, fuel, gene sources, human food, invertebrate food, materials, medicines, poisons and social uses. Users simply enter data on location, desired benefits and climate, then GlobUNT sifts through the database and returns a recommendation for a specific mix of species that fits the bill.

“Many current tree-planting initiatives for forest landscape restoration fail because they do not sufficiently consider the needs of the local communities who plant and tend them,” the researchers wrote last month in a paper in Nature describing the new resource. “[F]or any country where a project aims to implement tree planting schemes that aspire to maximise native tree biodiversity while addressing local community needs, GlobUNT will be a user-friendly source for practical information.”

— October 3, 2023

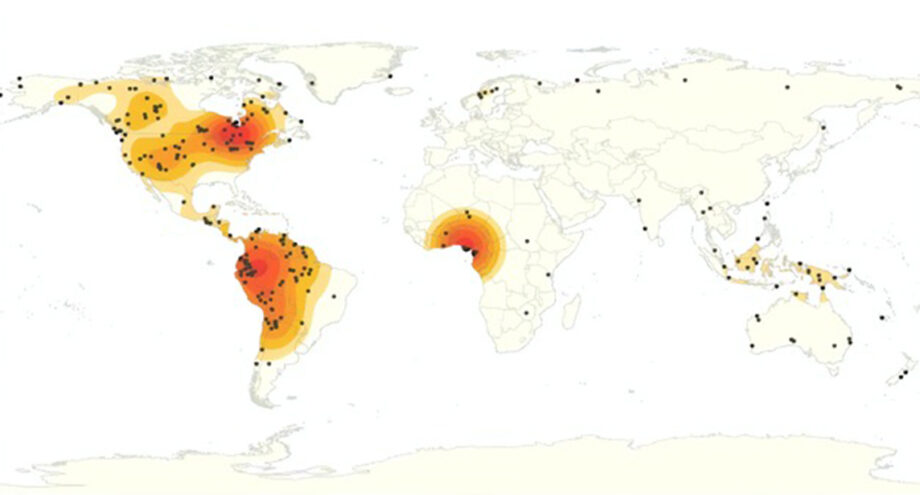

China, Brazil and Iowa may not have a lot in common, but one thing they do has literally life-and-death consequences for people around the world: All are hot spots of antimicrobial use in food animals.

Penicillin and other antimicrobial agents have long been used to beat back infections in livestock. But in recent decades farmers have increasingly been using such drugs to bump up healthy animals’ ability to grow bigger and produce milk by preventing infections and altering digestive tract bacteria in a way that makes more nutrients available to the animal. As a result, the use of antimicrobials has skyrocketed — and with it, the risk of microbes’ evolving resistance to them. That bodes ill not only for continued effectiveness of these life-saving drugs in food animals, but in their ability to fight infections in humans as well.

A study published in the journal PLOS Global Public Health by researchers from Europe and India used data from 42 countries to estimate global antimicrobial use at 99,502 metric tons (109,682 tons) in 2020. Nearly 60% of that occurred in just five countries: China, Brazil, India, the United States and Australia. Factoring in trends in food animal production and antimicrobial use, the researchers projected that antimicrobial use could rise to 107,472 metric tons (118,468 tons) by 2030 — an 8% increase.

The planet’s most important stories — delivered to your inbox

Be the first to hear about important new environmental stories. Sign up now to receive our newsletter.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Noting the potential severe consequences for human and animal health, the researchers called for reporting antimicrobial use on a country level.

“Availability of national data would enable comparisons within regions that have large discrepancies between countries, and perhaps more importantly, relate antibiotic stewardship policies (or absence thereof) with accurate [antimicrobial use] levels,” the researchers concluded. Doing so could help better achieve the World Health Organization’s call to reduce antimicrobial use and thus help ensure these drugs retain their capacity to heal humans and livestock alike.

— July 6, 2023

A global environmental problem that Ensia shone light on in 2016 is worse than suspected, researchers inspired by our reporting have found.

While the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates suggest global pesticide use is plateauing, Indiana University assistant professor of geography Annie Shattuck and colleagues, writing in the July 2023 issue of Global Environmental Change, report that use is actually growing.

Motivated by the need to accurately estimate the magnitude of pesticide use in order to work toward the Convention on Biological Diversity’s commitment to reducing pesticide risk, the researchers combined FAO data with trade statistics for 137 countries. Globally, they found a 20% jump in pesticide use between 2008 and 2018, with a 153% increase in low-income countries. Likely contributors include increased availability of inexpensive pesticides, rural development and changes in supply chains.

— June 27, 2023

When people think of turning the tide on climate change, we often think of reforming energy use. But there’s another group of actions with big potential for averting climate crisis: improving our interactions with the land. A report released last September by Conservation International in partnership with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, WWF and Exponential Roadmap Initiative describes how altering agricultural and other land use practices could make a substantial contribution to stabilizing climate for future generations.

When people think of turning the tide on climate change, we often think of reforming energy use. But there’s another group of actions with big potential for averting climate crisis: improving our interactions with the land. A report released last September by Conservation International in partnership with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, WWF and Exponential Roadmap Initiative describes how altering agricultural and other land use practices could make a substantial contribution to stabilizing climate for future generations.

Currently, the way we use land adds some 12.5 gigatons (Gt) of greenhouse gases to Earth’s atmosphere every year, one-quarter of humanity’s total contribution. The biggest opportunities to reduce this come from improved farming and grazing, eating more plant-based diets, reducing food waste, and improving forest management.

The report, “Exponential Roadmap for Natural Climate Solutions,” outlines a specific strategy for bringing net land-sector emissions to zero by 2030 and enlisting land in soaking up another 10 Gt by 2050. The plan focuses on three broad categories: protect “natural lands,” better manage land we use for our own needs and restore damaged land to a healthier condition. Specifically, it describes a need for four key categories of action:

● Boost carbon storage in soil, plants and other natural systems

● Improve food production and consumption

● Tap into traditional practices to improve how we use land

● Stop destroying and start restoring forests

If followed, the researchers say, the roadmap could make a substantial contribution to putting the planet on the path to a more stable climate. It also can provide ancillary benefits in the form of reducing hunger, protecting biodiversity and more.

“In the next decade we need to turn working lands — from agriculture and grazing lands to forestry — from vast emitters of greenhouse gases to enormous stores of carbon. At the same time we must scale up carbon storage in existing ecosystems: forests, wetlands, peatlands and grasslands,” Potsdaam Institute for Climate Impact Research director Johan Rockström writes in a foreword to the report. “If we start today, we can safeguard the climate, our societies, and the Earth for future generations. This is a golden opportunity. Let’s take it.”

— February 17, 2023

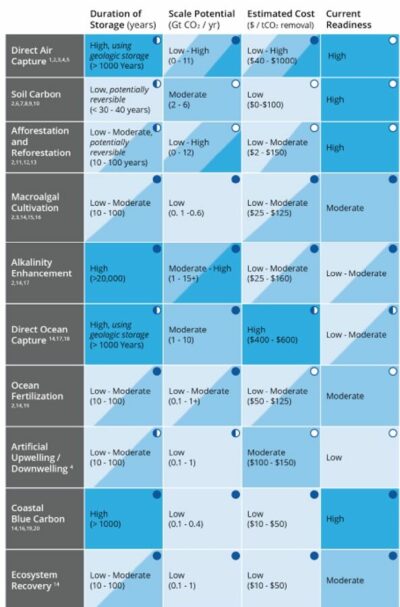

As the impacts of climate change become more visible in everyday life, attention is increasingly turning to ways to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere and so minimize further harm. A new report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) provides a valuable overview of various approaches to doing so.

In November 2020, NOAA’s Carbon Dioxide Removal Task Force was charged with looking at research needs around various carbon dioxide removal strategies, from direct air capture to boosting land and ocean ecosystems’ ability to absorb the gas. Its newly released report summarizes pros and cons of various approaches and describes what we need to learn and how NOAA can contribute.

Strategies assessed were:

Direct air capture: using absorbent material to trap CO2 from the air and then converting it into a substance that prevents it from easily escaping back into the atmosphere.

Soil carbon: boosting the ability of soil to store carbon.

Afforestation and reforestation: planting trees.

Macroalgal cultivation: farming CO2-absorbing seaweed or encouraging its growth in nature.

Ocean alkalinity: increasing ocean water’s ability to store carbon by increasing its pH.

Direct ocean capture: removing CO2 from ocean or other water so it can trap more.

Ocean fertilization: adding nutrients to ocean water to accelerate carbon uptake by photosynthesizing organisms.

Artificial upwelling/downwelling: bringing nutrient-rich water up from the depths of the ocean to the surface where it can feed carbon-trapping life forms and/or sending carbon-rich surface water to the depths.

Coastal blue carbon: Storing carbon that runs off upland areas or is absorbed by plants that inhabit ocean coasts in the soil.

Ecosystem recovery: rehabilitating ocean ecosystems to enhance organisms’ ability to absorb carbon and eventually store it on the ocean floor.

For each strategy, the group summarized research related to how long the approach could store carbon, its ability to scale, its relative cost and the extent to which it can be deployed with existing capabilities.

The figure below summarizes various attributes of the Carbon Dioxide Removal approaches assessed. The darker the blue shading, the more favorable the approach with respect to the attribute. Circles indicate NOAA’s ability to address the particular approach and attribute. Click the image to expand.

“[N]egative emissions strategies will be essential for keeping global temperatures at or below target levels,” the authors write. “Many of these techniques are promising in theory, but require additional research to evaluate their effectiveness and scalability, and explore potential co-benefits and environmental risk.”

— January 26, 2023

What’s in that IV bag besides saline and medication? As we become more aware of the harms of chemicals embedded in plastics and other materials, consumers — including patients — are demanding a higher standard.

Research suggests that the presence of certain chemicals in some healthcare equipment can compromise the benefit of the treatment the equipment enables. For example, the presence of chemicals in intravenous equipment could reduce the effectiveness of the medication being administered and alter hormonal function in patients.

In response, the nonprofit organization Clean Production Action recently created a process to certify health-care products that do not contain specific chemicals such as polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) that are associated with cancer, altered brain development, endocrine disruption and other health harms.

To earn certification for a product under the new GreenScreen Certified Standard for Medical Supplies & Devices, health-care product manufacturers must follow basic principles of green chemistry and prove it is formulated without disallowed chemicals through rigorous testing. They also need to recycle or otherwise address waste implications of both the product and its packaging.

Various levels of certification are available depending on the level of strictness the manufacturer wishes to pursue with respect to different chemicals. Manufacturers can use the certification to show consumers that they are conscientious about avoiding harm and to identify products that contribute to meeting consumers’ environmentally preferred purchasing (EPP) goals.

In addition to healthcare equipment, Clean Production Action also offers certifications that apply to textiles, cleaners, degreasers, firefighting foam, fabrics, furniture and food service equipment.

— November 11, 2022

When it comes to advancing sustainable agriculture, customized, in-person guidance makes a difference. That’s the conclusion of a study on improving Brazilian cattle ranching published earlier this month in the scientific journal PNAS.

When it comes to advancing sustainable agriculture, customized, in-person guidance makes a difference. That’s the conclusion of a study on improving Brazilian cattle ranching published earlier this month in the scientific journal PNAS.

Researchers from the U.S. and Brazil led by Arthur Bragança of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro wanted to find out how well various approaches to sharing climate-friendly practices with cattle ranchers influenced whether those practices were actually used. They provided 56 hours of coursework on practices such as restoring pastures, cultivating forests and using no-till agriculture to a group of 706 ranchers who operate mid-sized ranches in Brazil’s Cerrado biome. Of these, 311 were also offered a series of 24 in-person visits from agricultural extension agents over a period of two years, along with advice customized to their individual circumstances.

Producers who received the training alone by and large did not increase adoption of the climate-friendly practices, while those who received the technical assistance did. The researchers found that the implemented changes increased productivity and also reduced carbon dioxide equivalent emissions by an estimated 1.11 million metric tons (1.22 million tons) per year and provided additional carbon sequestration benefits as well. And adoption was not only good for the environment, it also offered an 8–45% return on investment in the form of increased profits for producers.

“Our analysis provides strong empirical evidence that customized, individual agricultural extension can provide farmers with the knowledge and skills needed to restore pastures and adopt new management practices that support sustainable intensification and increase income,” the researchers conclude.

The work is important because livestock farming is responsible for nearly 15% of the greenhouse gas burden humans are adding to the atmosphere, and Brazil is among the top cattle-producing countries in the world. The practices that the training and technical assistance encouraged can reduce the need to destroy carbon-sequestering forests and enhance the ability of the ranching practices to keep carbon in the soil. — March 24, 2022

Lobster claws and insect exoskeletons may seem like unlikely candidates for sustainable packaging feedstock. But researchers are hot on the trail of turning a molecule these structures contain into the basis of packaging for food and other products that’s not only made from a resource that can be renewable if sourced in a sustainable way, but also has a spectrum of desirable traits, from extending food shelf life to imparting antioxidant properties.

The compound, chitosan, is readily derived from chitin — one of the most abundant biological polymers in the world, second only to cellulose and found in fungi as well as insects and crustaceans. Chitosan offers plenty of potential benefits to the packaging industry in addition to being made from a compound that’s available pretty much everywhere. It’s biodegradable and naturally impedes the growth of bacteria and fungi. It could substitute for fossil-fuel-based feedstocks for plastics, reducing the demand for materials that contribute to climate change. Because it’s nontoxic, it has potential to be used for edible protective coatings for foods such as fruits, vegetables, eggs and coffee beans. But it also poses some challenges: Films made from chitosan tend to brittle and permeable to water.

Assessing strategies for capitalizing on the benefits and reducing the downsides of chitosan-based packaging is the focus for a team of researchers from Malaysia, Iran, Sri Lanka, Saudi Arabia and Australia writing in the February 2022 issue of Carbohydrate Polymers. With an eye to moving the functionality forward, the researchers reviewed the state of knowledge regarding various ways to modify chitosan and combine it with other substances to enhance its potential for packaging.

They found numerous research efforts that shine light on potential strategies for moving the substance toward commercial use. Modifications shown to improved characteristics useful for packaging materials include:

- Cuttlefish skin gelatin increased tensile strength of packaging film.

- Zinc oxide nanoparticles and nettle leaf extract boosted antibacterial properties.

- Aloe vera, oregano, thyme, anise or cinnamon helped reduce fungal growth.

- Kombucha tea improved water vapor permeability and antioxidant properties.

“Although the research on practical applications of chitosan packaging films is at its infancy,” the researchers concluded, “we believe that with the recent emergence of nanomaterials and/or bioactive ingredients, the face of chitosan-based packaging will drastically evolve and open several interesting new window of opportunities for the design of scalable and low-cost hybrid materials over the next few years.” — January 27, 2022

Would you alter the way you do things to help reduce the severity of climate change? If so, you’re not alone. A recent survey of individuals in 17 “advanced economies” found that 80% of respondents were willing to modify some aspects of their work and lifestyle to help mitigate the threat.

Would you alter the way you do things to help reduce the severity of climate change? If so, you’re not alone. A recent survey of individuals in 17 “advanced economies” found that 80% of respondents were willing to modify some aspects of their work and lifestyle to help mitigate the threat.

The survey, conducted in early 2021, assessed the opinions of 16,254 individuals from 16 “advanced economies” by phone and another 2,596 in the U.S. via the internet. It included a broad range of questions related to beliefs and attitudes regarding climate change actions. Countries included in the survey were Canada, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the UK, the U.S., Australia, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.

A drill-down into the data by traits such as gender, nationality and political persuasion offers insights for individuals, organizations, governments and others seeking to mobilize individuals to help mitigate risks. Among the more specific findings:

- Individuals on the political left tended to be more willing to make changes than those on the ideological right.

- Young adults were more likely to be amenable to change than older adults.

- Higher educational attainment was positively correlated with more willingness to change.

The survey also found that willingness to change varied from one country to another. The range in proportion of respondents “willing to make … changes about how you live and work to help reduce the effects of global climate change” ranged from 93% for respondents from Italy to 55% for those from Japan.

The survey also assessed a number of other attitudes and beliefs related to climate change and climate action. These included how concerned respondents were that climate change would harm them personally; how well they think society is responding; and whether climate action is good for the economy. Again, responses were broken down by demographic group, yielding some additional insights:

- Except for Sweden, most respondents were at least somewhat concerned that climate change will hurt them. This was generally more true for ideological left than right, for women than for men, and for young people than for older adults.

Respondents were generally favorable regarding how well their own society is dealing with climate change. Results were mixed as to whether the international community is doing a good job.

Overall, the survey offered encouraging news for those hoping to make inroads into climate change, noting that while it “reveals a growing sense of personal threat from climate change among many of the publics polled,” it also indicates that “[p]ublic concern about climate change appears alongside a willingness to reduce its effects by taking personal steps.”

— December 28, 2021

Archaeological records have long helped scientists discover past important events, learn about extinct species and explore past ways of life. Might ancient history inform efforts to deal with climate change as well? Researchers from the U.S., Canada and France think so. In their recent study, the researchers tapped archaeological records to show how humans have faced climate challenges in the past — providing valuable insights into how various degrees of warming affect current and future droughts, erratic weather, sea-level rise, and more.

The researchers note that many current efforts to deal with global warming are ineffective. “Planning a sustainable response to climate change requires us to identify the critical climate thresholds capable of disrupting social, economic, or political systems and culturally appropriate strategies for countering such disruptions,” they write. Because the archaeological record encompasses cultural, geographic and temporal diversity, it can show how a wide range of human cultures have responded to a wide range of unpredictable climate events in the past — and shine a light on how we might best do so in the future.

We have a lot more technology for understanding and interpreting the archaeological record now than we did in the 20th century. And methodological and theoretical advances in climate research in recent decades have made it possible to study past human-environmental interactions, which enhance understanding of the underlying reasons for change in the archaeological record. A glance at the record, with help from increasingly sophisticated climate modeling and advanced computing, is shedding light on human responses to a changing climate. Awareness of past distribution of plants and animals, for example, helps climate scientists fine-tune models that predict future conditions.

“The archaeology of climate change has an important role to play, highlighting the importance of cultural diversity and encouraging scientists, policymakers, and stakeholders to engage with the past to help plan a sustainable future.”

Insight into past human behavior and perspectives from various past cultures are relevant because scientists expect climate change to alter our food supply and farming practices. Looking at the adoption of farming in Southwest Asia during the most recent glacial/interglacial cycle, for instance, the researchers found that climate changes produced different outcomes depending on social and geographic circumstances. Based on this, they determined that “periods of favorable climate led to economic and cultural experimentation, which acted as an investment, making the society more resilient against future periods of climatic downturn.”

The researchers looked to ancient indigenous communities as examples of resilient communities that take an ecosystem-based approach to working with the land that protects biodiversity and themselves. For example, as glaciers melted, ancestors of today’s Cree people tended to settle in places that experienced fewer transformations due to the changing climate. Long-ago farmers in the southern hemisphere were able to adapt to disruptions brought on by El Niño events. This knowledge underscores the importance of protecting cultural diversity.

“[M]any past adaptations to climate change were highly successful and could be readapted to modern contexts,” the researchers write. “A comparative, cross-cultural study of the human past demonstrates that cultural diversity has been, and remains, a key element of human resilience.”

As population rises, climate changes, food security declines, and the need for sustainable farming practices and ethical water management grows, archaeological perspectives will become increasingly important for informing decision making.

— December 6, 2021

In 2021, we are no strangers to the throes of climate change, with examples including the ongoing drought in the Western United States and recent flooding in Germany and Belgium. Flooding, particularly on coasts, threatens families and communities.

In a recent study published in the academic journal Earth’s Future, researchers looked at the costs of coastal flooding through an equity lens, finding that flooding comes with both monetary and social risks, suggesting that many people who own or rent homes at risk from rising sea levels may not have enough money to pay for the associated damages.

“The impact of coastal flooding on communities hinges not only on the cost, but on the ability of households to pay for the damages,” the researchers write.

The study, which analyzed counties in the San Francisco Bay Area, projected flooding impacts from 2020 to 2060, determining that coastal flooding disproportionately impacts lower-income households. Climate change has already altered the risk of certain natural disasters, like flooding, and is projected to worsen other hazards and potentially create future threats.

“The ramifications for the financial security of individual households and for the communities as a whole depend sensitively on the socioeconomic context,” the researchers write, emphasizing the social risk that comes with not being able to afford flooding damages.

That seems to hold true in the Bay Area: Using computer modeling, the researchers analyzed the risks associated with coastal flooding in the region, concluding that San Mateo County is particularly at risk — with a future financial burden possibly totaling as much as US$835 million — due to the high number of flooded buildings and a low average household income.

Future financial instability, the researchers observe, also threatens homelessness for those who cannot afford to pay for flood damages. The study notes that approximately 9,871 households in the Bay Area could be pushed into financial instability between 2020 and 2060, as flooding becomes more common alongside rising global temperatures and sea levels.

While their “estimates are specific to the San Francisco Bay Area,” the researchers write, “our granular, household-level perspective is transferable to other urban centers and can help identify the specific challenges that different communities face and inform appropriate adaptation interventions.”

The researchers note that with continued greenhouse gas emissions, the severity of flooding may increase, which could manifest as larger coastal flooding damages in the mid-21st century — leaving a short, valuable runway of time to mitigate that risk. The study suggests that in order to mitigate flooding risk, researchers and practitioners may need to differentiate communities’ peril into two categories: monetary risk and social risk.

The researchers float potential ideas for change, including improvements to the National Flood Insurance program to better assist people facing monetary risk. Such an update could create a voucher program to help individuals pay for the damages to their homes, ideally shielding households from at least some future financial instability.

Sea walls, the study proposes, could strengthen coastal infrastructure, protecting buildings and the people that live within them.

However, the researchers note, these avenues alone may not amount to a fully equitable approach: While flood insurance, as an example, offers vital protection for some people, it’s not always affordable, even with public assistance. The study suggests that community action, when aided by county, state and federal action, could help to develop support plans for financially unstable households to prevent further social risk.

Ultimately, “instead of adopting a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach that only targets monetary risk,” the researchers write, “we suggest co-producing a wider spectrum of adaptation strategies that is conscious of social risks and prioritizes community needs.”

Editor’s note: The main image is courtesy of D. Loftis/VA Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

— October 26, 2021

For many of us, March 2020 marked a pivot point in our lives, when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Since then, we have heard the term “wet market” thrown around in science and in the news, as a wet market in Wuhan, China is the site of the first cluster of cases of COVID-19.

In the wake of the pandemic’s emergence, some public health officials, lawmakers, celebrities, and average citizens called for a blanket closure of wet markets. However, a recent study published by researchers at Princeton University suggests that an across-the-board ban on wet markets would do more harm than good. Many people depend on wet markets, which often resemble the farmers markets of Europe and the U.S., for essential goods and services. Banning them altogether, the study contends, would spark pushback from vendors and customers and likely push wildlife trade further underground.

Another problem is that not all wet markets are the same: “Wet markets are often incorrectly conflated with live-animal or wildlife markets,” the researchers write. In fact, vendors at many wet markets simply sell fresh fruits, vegetables, fish and meat, with meat only from dead, domesticated animals. The study notes that imprecise language — statements conflating one type of traditional, innocuous market, commonly found in countries like China, with different kinds of markets — can inflame xenophobia against people from east and southeast Asia, regions where wet markets are the main, or only, source of food for many people.

As an alternative to sweeping generalizations and complete closures, the researchers offer what they call a “taxonomy of wet markets,” classifying risk based on whether the markets feature live or dead animals, and whether the animals sold were domesticated or wild. More targeted approaches to regulation, they conclude, might be a more viable way to safeguard human health.

One way that some markets might pose a threat to human health is by potentially fostering emerging infectious diseases (EIDs). “In general, the building blocks of an EID event (the emergence of a novel infectious disease in humans) consist of interspecific zoonotic transmission, viral amplification, and viral modification,” the researchers write.

The study identified key risk factors for diseases making the jump from animals to humans at markets: the presence of high disease-risk taxa and live animals, hygiene conditions, market size, the density of animals, interspecies mixing and the length and breadth of animal supply chains.

Potential dangers aren’t limited only to human health, either, since some markets also pose risks to biodiversity. Currently, the study notes, wet markets only assess biodiversity risks based on the types of animals being sold, rather than the condition in which the animals are sold. Certain markets have become a conduit for the sale of threatened or declining wildlife species, an illegal practice, and it is those markets, the researchers write, that pose the highest threat to biodiversity.

To guide effective regulations, the researchers have divided wet markets into four categories. The first includes wet markets that sell no live animals except seafood, which historically carries less risk of pathogens jumping to humans. The second classification covers markets that sell live domesticated animals, while the third covers markets that also sell dead wild animals. The final classification encompasses all of the above — plus markets that sell live wild animals. The risks to human health and biodiversity increase with the third and fourth classifications.

Based on these classifications, the researchers suggest that policymakers should prioritize regulating markets that pose the most risk — those in the fourth category, selling live, wild animals — to allow for the least amount of disruption in communities that depend on wet markets for food. “Most wet markets probably pose comparatively little risk to human health or biodiversity, but a few pose a disproportionately large risk,” the researchers write. Targeting such harmful wet markets, they contend, could help mitigate the threat of future pandemics and reduce risks to biodiversity.

Editor’s note: Main image, “Street Vendor | Pudu Wet Market,” by John Ragai is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

— September 1, 2021

Spring typically marks that time when insect pollinators begin the work that helps produce so many of the fruits and vegetables we love. In fact, researchers estimate that pollination accounts for about 9.5% of global agricultural production’s economic value.

However, global warming potentially threatens to cause mismatches, now and in the future, between these pollinating insects and the flowering plants that they help fertilize, according to a study published last summer by researchers from the University of Mons in Belgium. It’s a risk that merits more research: When it comes to plants, pollinators and the climate crisis, there’s still a lot we don’t know, the researchers write, and “to address this current knowledge gap, we need ambitious strategies for monitoring plants and their pollinators.”

Pollinating insects and flowering plants have a mutually beneficial relationship: The plant provides food to the insects, which spread pollen from one flower to another — helping the plant reproduce. But when warming temperatures alter one side of this relationship, there’s a risk that the whole process might be thrown off, potentially harming the insects, the plants and the broader ecological community.

According to the report, there is “growing empirical evidence” that bad timing can cause what scientists call phenological mismatches between plants and their pollinators. Global warming can influence living things’ life cycles, annual patterns and other activities, spurring situations where cycles that were once in sync no longer line up. If a plant flowers earlier than usual, for example, it might miss the window of time when its main pollinators are at work, leading to a potential decrease in seed production.

Observers most often note cases of bad plant/pollinator timing in the spring, so the researchers remark that spring-flowering plant communities could be more severely impacted. “Mismatches between the emergence of bee species and the blooming of their main resources have been specifically recorded,” the researchers write.

The researchers also point to another important, albeit more speculative, climate-related driver of plant-pollinator discordance: geography. Models simulating the future suggest that such geographical mismatches could happen if global warming shifts these species ranges and different species fail to match up and make pollination happen.

Plants and pollinators must be in the same area to help each other out, so if a changing climate pushes either party out of places they’ve long lived, it could sever that mutualistic relationship. Reductions in that spatial overlap could possibly leave some plants and pollinators without their essential counterparts. While changes relating to timing and life cycles are more established in scientific research, the study emphasizes that geographic mismatches could also be potential risks in a warming climate.

“Mismatches in the interactions between plants and pollinators will lead to the emergence of new biological networks and communities,” the researchers conclude. Some communities may lose interactions due to the changes in climate, but some may also gain new interactions. Better understanding of these dynamics is vital in a warming world because, the researchers write, “evidence for phenological mismatches as a result of microevolutionary responses has already been observed, thus a critical challenge is now to assess if the pace of adaptive evolutionary changes will be fast enough [to] track climate warming and prevent species extinctions.”

Author note: This article is dedicated to my grandfather, Stuart Bernstein, who died on January 4th after a long battle with heart disease. My Papa Stu inspired me to pursue a career in the environment and I know how much he would have loved to read this piece.

Main image, “Pollination,” by hernanpba is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 — June 14, 2021

If it did nothing else, the emergence of Covid-19 a year ago underscored for all of us the importance of anticipating and preparing for — and, as appropriate, steering the course of — things that might happen in the future.

That is, in a nutshell, the goal of the 2021 Horizon Scan of Emerging Global Biological Conservation Issues, recently published in the scientific journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution by Cambridge University conservation biologist William Sutherland and a team of 24 other conservation practitioners and researchers from around the world.

The team started by identifying 97 trends with potentially large impacts on conservation and biodiversity, then trimmed the list down to the top 15 that they agreed “society may urgently need to address.”

“Recent global assessments of biological diversity and climate change indicate negative trends and a rapidly narrowing window for action to reverse these trends,” the researchers wrote. “We believe that identification of novel or emerging issues for global biological conservation should inform policy making in the context of the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework and encourage research, discussion, and allocation of funds for continued tracking, in addition to informing management and policy change.”

The 2021 horizon scan is the latest in a series that stretches back more than a decade (read summaries of the most recent five here). In addition to making their predictions for the year ahead, the team members reviewed selections from the first horizon scan, published in 2009. They found that one-third of the issues identified in that scan “have since developed into major issues or caused considerable environmental impacts.”

Here are the issues that bubbled to the top in this year’s scan:

Suffocating Reefs

Coral reefs have come under siege from many threats in recent decades, from invasive species to warming waters to harmful fishing practices. Increasingly worrisome is hypoxia-associated coral mortality — suffocation from a lack of oxygen due to an influx of nutrients from land or aquaculture facilities into ocean waters. Because warm water holds less oxygen than cold water, scientists fear that climate change will only make this problem worse. Deoxygenation of ocean waters already has harmed corals in relatively small spaces such as bays and lagoons. Although we know relatively little about how resilient corals might be to low oxygen, there is concern that in some cases it could be the straw that breaks the camel’s back for these valuable and beleaguered ecosystems.

Iron-Fortified Coasts

Ocean coastlines are abundant sources of plant and animal life — and those in polar zones are becoming increasingly so due to climate-change-induced melting of glacial and floating ice that contains relatively large amounts of iron. Plants need iron to photosynthesize, so melting ice stimulates plant growth. This increases coastal ecosystems’ ability to soak up planet-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and potentially harmful nutrients running off land and boosts the food supply for other living things in the area. But as the trend continues, it also is likely to alter biodiversity and ecosystem structure and complexity along polar coastlines in unknown ways, even as it enhances biological communities’ ability to mitigate climate change through carbon sequestration.

Waves of Change

Heads up, ocean ecosystems: Global energy trends are about to bring major waves of change. Numerous offshore oil and gas rigs as well as first-generation offshore wind turbines are slated for decommissioning in the near future. A variety of strategies might be deployed for doing so, from removing all or part of an installation, to converting it to an artificial reef, to simply abandoning it. At the same time, new ocean-based wind energy installations and natural gas wells will be coming on line. These upcoming changes in ocean-sited infrastructure could have big impacts on habitat in the vicinity — for better, for worse, or for both, depending on the location, the extent to which existing infrastructure has been colonized by marine life, and specific implementation strategies.

Seabird Patrol

Ocean-going vessels carrying out illegal fishing activities have ways of covering their tracks, from deactivating electronic tracking systems to avoiding the use of lights at night. The difficulty of finding such covertly operating boats on the vast open seas can be a limiting factor in efforts to prevent illegal activities that lead to overfishing and biodiversity degradation. In an interesting twist on surveillance, scientists are looking at enlisting albatrosses and other ocean-going birds to help track down troublemakers. The birds, which naturally follow fishing vessels in hopes of grabbing morsels, can be fitted with transmitters that can clue enforcement officials in to their location. Work is already underway to evaluate the approach — including consideration of the extent to which it might put the birds themselves at risk of harm.

Location Spoofing

Although seabirds may be attracted to fishing boats, they’re not quite as helpful when it comes to tracking vessels that aren’t flinging fish bits off the back. Currently it’s possible to identify and pinpoint the location of most such ships using Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) and Automatic Identification Systems (AIS). However, technologies are emerging that allow those wishing to avoid detection due to surreptitious activities to muddle their identification and coordinates. Such technologies, conservation biologists speculate, could make it easier to transport illegal animals or animal parts, engage in illegal mining, or conduct other covert activities. Efforts are underway to develop technologies to thwart such deceptive practices, but it could be a decade before they are ready to deploy.

Long-tail Hormones

It’s bad enough for pollutants to harm animals that come in contact with them. But now there’s evidence that some water-polluting chemicals that alter endocrine systems in fish can get passed to future generations as well. By mimicking or blocking the proper function of hormones, such compounds, which include many used in households and on farms, can cause deformities and fertility issues. And now it appears that in some species, parents can pass those disruptions to the next generation. Concerns are growing that this long-tail impact will be found in other animals as well.

Low-Hanging Clouds

Among the little-known prospective victims of climate change are the low clouds that hang over coastal oceans near the equator, helping to cool the atmosphere. The nature and extent of these clouds depend on a variety of conditions that are expected to change as our climate warms, including ocean temperatures, air movement in the atmosphere and the layout of coastal lands. Changes in the cloud cover, in turn, could affect the clouds’ ability to counteract global warming, preserve the conditions in which human settlements and ecosystems have evolved to thrive, and exacerbate fire risk in the region.

Trillion Tree Trouble?

Numerous groups have begun promoting extensive planting of carbon-dioxide-absorbing trees as a way to help counter the climate-disrupting rise in the concentration of greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere. But massive tree-planting efforts are not without concerns. Even as proponents tout the approach to climate change mitigation, others warn of potential problems. For one thing, poorly sited plantations could end up replacing ecosystems that actually sequestered more carbon than the trees do. For another, biodiversity could take a hit in the process as species-rich native habitats are replaced by monoculture plantations with the primary goal of socking away CO2. Careful planning will be needed to ensure such initiatives don’t do more harm than good in the long run.

Fire Prevention Logging

As climate and other conditions change, the intensity and severity of wildfires are increasing in North America, Australia, central Africa and elsewhere around the world. One strategy that’s been proposed to reduce the risk is to reduce the number of trees available to burn. Some research suggests that such a strategy could do little to decrease the likelihood of harm to humans and property, and in some instances could even increase it. Nevertheless, with strong public pressure to do something about this growing problem, there is a real likelihood that policy makers will turn to tree thinning as a way to prevent wildfires — with certain but unknown impacts to the ecosystem and multiple species that call forests home.

Super Sustainable Farming

A quiet revolution is underway in India: the wide-scale adoption of sustainable intensification as a farming practice. Across the world’s second-most-populous country, state-level policies are incentivizing farmers to adopt a suite of practices that reduce the adverse environmental impacts of agriculture while boosting crop yields, income, health and well-being. To date, more than a quarter-million farmers have adopted the new approach, which includes eliminating synthetic inputs, enhancing crop diversity, rotating crops and more. Millions more are expected to follow the practice, which is also known as natural, community-based or zero-budget farming. As success stories roll in, the initiatives could set off a snowball effect, leading other countries and farmers to follow suit.

Navigation Miscues?

If you’ve ever mistaken a satellite for a star in the night sky, you’ve had a taste of the confusion scientists fear might face some birds, mammals and insects in the future. Some 2,600 artificial satellites currently circle our planet, and booming communications technologies are expected to catalyze the deployment of thousands more. What do these plentiful extra points of light mean for animals that use the stars for navigational cues? No one know for sure — but it’s a question worth investigating before permanent damage is done to populations already beleaguered by human impacts on the surface of the Earth.

The planet’s most important stories — delivered to your inbox

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Stranded Energy Meets Bitcoin

At certain times and in certain places around the world, the ability to generate electricity exceeds demand, as limited by economics or logistics. The excess capacity — whether methane byproducts from oil drilling or wind or solar power that exceeds local demand — may just go to waste due to market logistics. But what if a pop-up demand were available to use this “stranded energy” on an as-needed basis, at a discounted (but better than throwing it away) price? Recently, Bitcoin mining — an energy-intensive process required to keep transactions fair — has been emerging as a possible contender. Bitcoin mining is relatively flexible when it comes to time and place, so it could create a low-payout-but-better-than-nothing use for these resources. There is some concern by those working to mitigate biodiversity-compromising climate change that using Bitcoin to close the use-capacity gap could boost use of fossil fuels — but also optimism that it might help make renewable energy sources more economically desirable.

We’re All Detectives Now

If officials don’t notice or respond to environmental problems, are they still problems? Environmental quality in many regions around the world is limited by insufficient monitoring, detection, prevention and mitigation of pollution or other assaults. But that could change, thanks to emerging technologies. Because of the growing adoption of smartphones and internet connectivity, private citizens around the world are being empowered to act as environmental detectives, identifying and calling out problems they identify through social media mining. This approach already has been used to document locust swarms in East Africa. As more and more people connect, it could be applied around the world to detect and encourage responses to environmental assaults of all sorts, from water pollution to wildlife poaching.

Self-Healing Buildings

In the Department of Good News, the development of self-healing building materials bodes well for biodiversity in a variety of ways. Such materials, which are based on a variety of inputs, including chemicals and bacteria, aim to enhance the ability of build structures to bounce back from damage without the need to repair or replace them. They could be beneficial in a number of ways. For one, they can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by reducing the need to produce concrete and carry out construction projects to repair or replace damaged structure. For another, they can reduce the need to mine or quarry new materials, processes that often involve destroying habitat for plants, animals and other living things. In addition, they can reduce the production of construction debris and the accompanying increased demand for landfill space.

Baltic-Black Connection

— December 3, 2020

From research scientists to political organizers, people around the planet are working to thwart a threat whose scale has become increasingly clear: Global heating is spurring a climate crisis of megafires, superstorms and record-setting heat waves that current policies are not enough to address.

Many climate activists, driven in part by the youth movements of Gen Z, are joining major scientific bodies in calling for economic and social transformation, while other onlookers are hoping for “moonshot” technology to step in as climate “savior.”

How did we end up here? Answers to that vary, but research published earlier this year in the journal Nature Climate Change puts at least some of the blame on a surprising villain: computer modeling–based on wishful thinking.