July 6, 2023 — China, Brazil and Iowa may not have a lot in common, but one thing they do has literally life-and-death consequences for people around the world: All are hot spots of antimicrobial use in food animals.

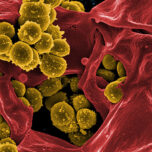

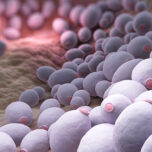

Penicillin and other antimicrobial agents have long been used to beat back infections in livestock. But in recent decades farmers have increasingly been using such drugs to bump up healthy animals’ ability to grow bigger and produce milk by preventing infections and altering digestive tract bacteria in a way that makes more nutrients available to the animal. As a result, the use of antimicrobials has skyrocketed — and with it, the risk of microbes’ evolving resistance to them. That bodes ill not only for continued effectiveness of these life-saving drugs in food animals, but in their ability to fight infections in humans as well.

A study published in the journal PLOS Global Public Health by researchers from Europe and India used data from 42 countries to estimate global antimicrobial use at 99,502 metric tons (109,682 tons) in 2020. Nearly 60% of that occurred in just five countries: China, Brazil, India, the United States and Australia. Factoring in trends in food animal production and antimicrobial use, the researchers projected that antimicrobial use could rise to 107,472 metric tons (118,468 tons) by 2030 — an 8% increase.

Noting the potential severe consequences for human and animal health, the researchers called for reporting antimicrobial use on a country level.

“Availability of national data would enable comparisons within regions that have large discrepancies between countries, and perhaps more importantly, relate antibiotic stewardship policies (or absence thereof) with accurate [antimicrobial use] levels,” the researchers concluded. Doing so could help better achieve the World Health Organization’s call to reduce antimicrobial use and thus help ensure these drugs retain their capacity to heal humans and livestock alike.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!