September 11, 2020 — My parents tell me that as a kid I spent hours sprinting around our backyard making strange noises as part of my imaginary adventures fighting space pirates or finding dragons. I pulled from the science-fiction and fantasy books I was obsessed with to create worlds I’d roam through for hours. My mom recalls looking out the living room window, shaking her head at my weirdness, and ultimately leaving me to my own devices.

I learned a lot from these forays into imaginary worlds, but perhaps the most important lesson was that assuming that the future will be a straight-line continuation of the present is unimaginative, boring and ultimately incorrect.

Most things aren’t linear — a fact we see play out over and over again in our daily lives. When doctors give us medicine, we ask about side effects. We invest in the stock market with hopes of high returns and money saved, only to see the market suddenly crash. We complain about the local weather station’s inability to give us an accurate forecast. We all began 2020 with very different visions of how it was going to go.

It’s no different with our planet. As a paleoecologist, I look back on Earth’s history and see ancient records of ice ages, abrupt extinctions and evolution of new species that have shaped life’s trajectory in sometimes delightful (and other times terrifying) ways. Climate scientists do much of the same for what the future of our climate system may look like. Decades of research have been spent examining and understanding the complex, nonlinear connections between different parts of our planet and incorporating them into climate models.

In many ways, we get away with ignoring much of this complexity in our day-to-day lives — the consequences being delayed or removed enough for us to blissfully not connect the dots. But when it comes to existential threats to humanity like climate change, we must take into account the messy way the world works.

Unintended Consequences

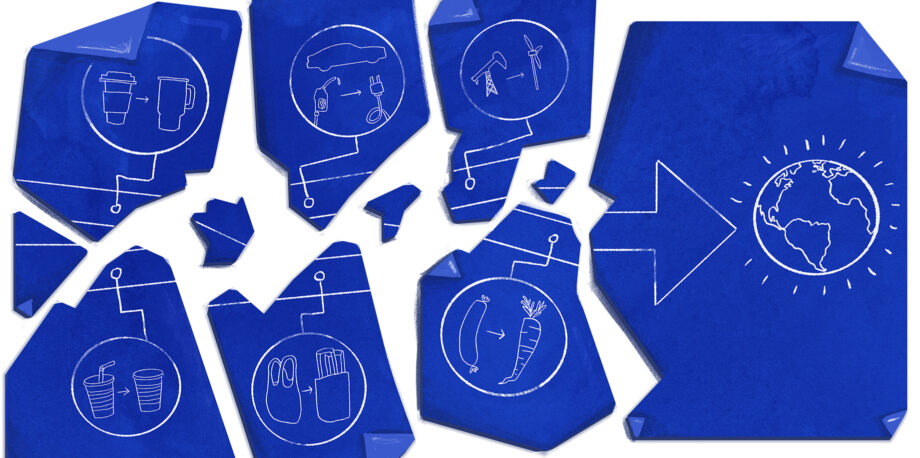

Yet many proposals to address environmental problems do just the opposite. They are rife with examples of linear solutions: buy a reusable mug, get a Tesla, use less plastic, put solar panels on your roof, go vegan. The presumption is that such activities — which at their core remain about consumption — are unequivocally beneficial, and they follow a linear way of thinking that imagines the same set of circumstances surrounding the decision to exchange one thing for another.

The problem is, solutions to climate change — and other environmental problems we face — unfortunately can’t be reduced to such a simple exchange.

That’s because any choice, green energy included, is littered with unintended consequences that are hard to predict and very often end up wiping away the gains we expected from them.

This idea is hardly new. British economist William Jevons noted in 1865 that innovations that led to increased energy efficiency of coal might, paradoxically, cause coal consumption to rise. The modifications to the steam engine made by James Watt (innovations that, ironically, jump-started the Industrial Revolution and increased our reliance on fossil fuels) made coal a more cost-effective power source. The price per unit coal dropped, which led to the increased application of the steam engine to power industry, and, well, the rest is history.

Green technologies don’t escape this predicament, now known as Jevons’ Paradox or the rebound effect.

A big problem with the rebound effect is that it, too, creates nonlinear consequences. For example, if you buy an electric vehicle, you might feel like you can drive more without accruing climate guilt. But, even though EVs are zero emission at the tailpipe, they are usually powered by electric grids reliant on fossil fuels and can therefore generate plenty of emissions.

Similarly, if you switch to a vegan diet to reduce your carbon emissions but use that action to justify other not-so-carbon-friendly activities such as flying more, your overall climate impact could grow rather than shrink.

Supposedly environmentally friendly actions can also have implications for social and environmental justice.

Some rebound effects are not so easy to see. Maybe, like me, you bought a coffee tumbler with the intention of avoiding the environmental damage caused by paper and plastic waste of disposable cups and straws. But what if that coffee tumbler is a bit larger than the single-use cup you used to get? You may end up drinking slightly more coffee (and perhaps cream) each day. Multiplied by many people making the same choice, the increase in coffee consumption and dairy products could cause more environmental harm than was avoided by reusables, given that both coffee and cream are linked to deforestation.

On top of all that, there’s the life cycle of each product to consider: Where did the materials to make it come from, and where will the product go when we’re done with it? My reusable mug is made of metals that have a much higher environmental impact than a disposable cup.

When you take these factors into account, I might need to use that reusable mug 1,000 times to make up for its overall environmental cost compared with a disposable one.

Social and Environmental Justice

Supposedly environmentally friendly actions can also have implications for social and environmental justice.

There is a good chance the lithium in an electric vehicle comes from places like the Salar de Atacama in Chile, where lithium-rich groundwater is pumped to the surface and evaporated away in one of the driest places on the planet. This threatens not only the ecosystem by drawing water away from the life-harboring lagunas of the region, but also the Indigenous communities that rely on these sacred waters and have called those lands home since time immemorial.

If your head is spinning, that’s sort of the point. The implications of the supposedly “green” choices we make are dizzying, unpredictable and in some cases, outright scary.

In many cases, what happens to these communities in the face of environmental injustices is that they are displaced to urban areas. When this happens, their traditional way of life is often replaced with one centered around consumption at huge environmental cost — at the same time their homeland risks loss of its stewards and so often the biodiversity they harbor, which is often comparable to that of protected areas. Most people wouldn’t suggest destroying national park areas or conservation sites for electric vehicles or any other “green” practices — yet that is exactly what we are doing to these communities.

Biodiversity and species endemism are not the only (or main) reason to fight for the sovereignty of Indigenous communities. Traditional ways of living should be valued regardless of the biodiversity of the land it is on. Yet, the displacement of these communities and destruction of their lands are both tied to extractive solutions, regardless of whether it is for “green” energy or not.

Dizzying Implications

If your head is spinning, that’s sort of the point. The implications of the supposedly “green” choices we make are dizzying, unpredictable and in some cases, outright scary.

In the past, economists and engineers have suggested that rebound effects might not wipe out all of the potential gains from altered technology or behavior. But no analysis can truly take into account the myriad indirect impacts — and more recent research into those likely underestimated impacts is already troubling.

While I am keenly aware of the impending impacts of not reducing emissions, I am also concerned about a world where we pick the wrong path forward, ignore complexity and try to rely on technological swaps, focused on consumer-driven solutions, to get us out of this mess.

If you feel nervous at this point, I’m right there with you.

As an Earth scientist, I’m incredibly concerned about climate change. Without any doubt, we need to get away from our addictive relationship with fossil fuels. Yet, while I am keenly aware of the impending impacts of not reducing emissions, I am also concerned about a world where we pick the wrong path forward, ignore complexity and try to rely on technological swaps, focused on consumer-driven solutions, to get us out of this mess. Swapping out fossil fuel–powered technologies and electrical grids with “green” counterparts without addressing underlying issues of consumption not only may fail to address rising emissions; it also may be socially and environmentally destructive.

A vocal minority is calling for alternatives to the current economic paradigm with its focus on consumption and pushing instead for a focus on degrowth. Degrowth on its own, however, would be unjust if applied unilaterally. Instead, what many proponents call for is a halt to consumption-based economic growth in wealthy nations and a redistribution of resources to regions with historically impoverished or marginalized populations.

It’s easy to imagine that we’re in the clear if we just switch energy sources, the types of cars we drive and the products we purchase to something sold to us as more eco-friendly. In reality, we ignore the complexity of the massive societal transition we face in favor of a “solution” that prioritizes the upkeep of an economy and allows us to keep on consuming.

Degrowth is often coupled with new research on urban metabolism, which takes a critical look at how to reduce emissions produced in cityscapes, but also looks at sustainability more holistically by focusing on overall resources going into cities and waste coming out.

Others say changing our relationship with our natural environment and looking to traditional communities to restore reciprocal relationships with ecosystems is key to moving forward. Part of this may include rewilding our landscapes and relearning how to live bioregionally (in sync with the unique context of the natural environment and human social, political and cultural systems that surround us), another active area of research.

At its core, these ideas all recognize that reducing greenhouse gas emissions is necessary but not sufficient to deal with the climatic and environmental problems in the decades to come. As award winning science-fiction writer Octavia Butler once wrote:

How many combinations of unintended consequences and human reactions to them does it take to detour us into a future that seems to defy any obvious trend? Not many. That’s why predicting the future accurately is so difficult. Some of the most mistaken predictions I’ve seen are of the straight-line variety — that’s the kind that ignores the inevitability of unintended consequences, ignores our often less-than-logical reactions to them, and says simply, “In the future, we will have more and more of whatever’s holding our attention right now.”

It’s easy to imagine that we’re in the clear if we just switch energy sources, the types of cars we drive and the products we purchase to something sold to us as more eco-friendly. In reality, we ignore the complexity of the massive societal transition we face in favor of a “solution” that prioritizes the upkeep of an economy and allows us to keep on consuming. We choose to ignore the most inconvenient truth of all: that a linear path from problem to solution is not possible, and much larger changes to our way of life will be needed to survive and thrive on Earth.

Climate change impacts are already embedded into our existence, and no path forward is without its own set of uncertainties. As low-carbon technologies augment our lives, we must also focus on re-creating our social, political and economic systems in a way that builds our collective adaptability and antifragility. As Jessica Flack, director of the Collective Computation Group at the Santa Fe Institute (SFI) in New Mexico, and Melanie Mitchell, the Davis professor of complexity at SFI and professor of computer science at Portland State University, recently wrote in Aeon, “living in a complex system requires us to embrace and even harness uncertainty. Instead of attempting to narrowly forecast and control outcomes, we need to design systems that are robust and adaptable enough to weather a wide range of possible futures.”

None of this will be easy. At its most base level it requires a deep recognition of the complex system we live in and a shift in the way we make decisions. It also, perhaps, suggests that we should use justice and equity rather than other metrics to measure human well-being.

We know now that there are many unknowns ahead of us, and that our tomorrows may not look very much like our yesterdays. This reality is both a challenge and opportunity. As kids roaming around our homes, with our parents shaking their heads, it once seemed easy for us to imagine radically different worlds. It’s time to reach back to those roots and acknowledge nonlinearity in a way that truly moves us toward solving the problems that got us here in the first place.

Editor’s note: The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily of Ensia. We present them to further discussion around important topics. We encourage you to respond with a comment below, following our commenting guidelines, which can be found on this page. In addition, you might consider submitting a Voices piece of your own. See Ensia’s Contact page for submission guidelines.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!