October 30, 2019 — The black rhinoceros is critically endangered, with fewer than 6,000 left in Africa. But last year, Kenya’s Sera Rhino Sanctuary welcomed the births of three black rhino calves. Sera is part of the Northern Rangelands Trust, which started with just two projects in northern Kenya and now includes dozens of community conservancies aiming to protect species while conserving natural resources. It’s an example of a conservation initiative starting small and spreading.

For biodiversity conservation efforts to have a big impact, they must scale up. But how does that happen? A study published earlier this month in Nature Sustainability offers some insights into what helps and hinders the dissemination of conservation programs, policies and projects.

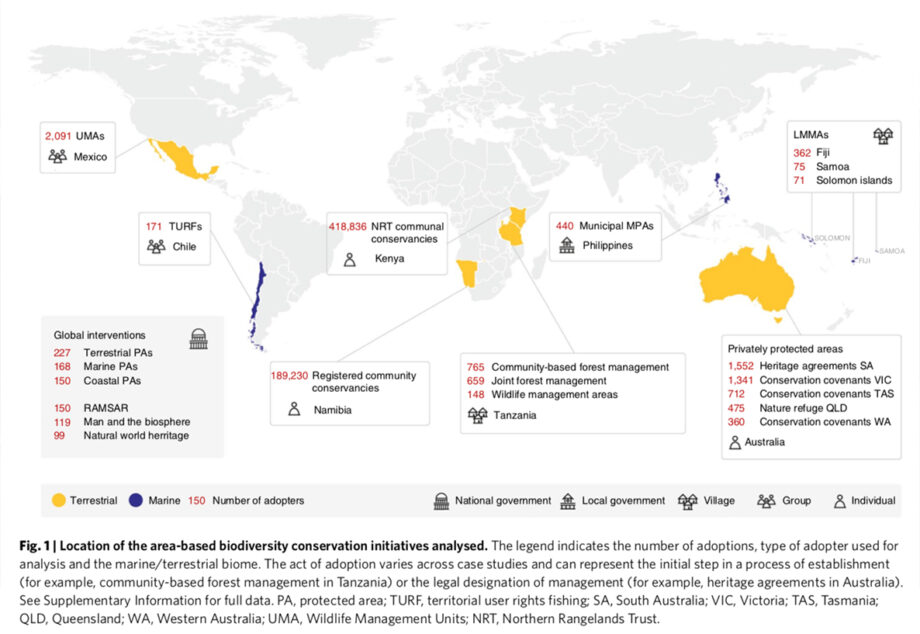

An international team of researchers led by Morena Mills, a member of the faculty of the Centre for Environmental Policy at Imperial College London, picked 22 conservation initiatives from around the world and analyzed how they spread over time. “Decision makers across the world are seeking conservation initiatives that display both rapid uptake and large-scale adoption,” the researchers wrote. But none of the case studies they examined had done both.

Roughly 80% of the case studies followed what the researchers called a “slow-fast-slow” dynamic. Under this pattern, conservation initiatives start small, with just one or a few government agencies, non-governmental organizations, communities or individuals adopting them. But as those adopters share their experiences, others adopt the strategy and share it, more stakeholders embrace the program and growth snowballs. Growth later slows again as the pool of possible adopters shrinks.

In the study’s data set, approaches that followed a slow-fast-slow dynamic include terrestrial and marine protected areas. This includes Ramsar sites, which are wetlands set aside for protection under an international treaty to conserve biodiversity and ecosystem services.

Other initiatives — about 20% of the case studies — saw fast adoption early on, after which the limited remaining pool of possible adopters caused adoption to slow. This “fast-slow” growth pattern, the researchers wrote, was associated with tighter regulation or more involved bureaucracy, including many programs mandated by governments or run by nonprofit groups. Wildlife management areas in Tanzania and marine protected areas created by municipal ordinances in the Philippines followed this pattern. So did Chile’s territorial use rights in fisheries (TURF) system, under which traditional fishers work within set-aside waters, collaborating with the government to promote sustainability while maintaining their livelihoods.

A range of factors appear to influence how quickly and widely a conservation model is adopted. Take, for example, Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMAs), an arrangement under which coastal villages govern resources sustainably in their local waters. The researchers noted that in Samoa, the government gave boats and aquaculture resources to communities that adopted the approach. That top-down intervention led to a quick spread of LMMAs, after which growth slowed. In contrast, the researchers explained, people in Fiji and the Solomon Islands had “a stronger bottom-up role.” In those countries, communities were slower to embrace LMMAs, but their implementation lent more weight to community empowerment.

Bigger data sets on the implementation of biodiversity conservation initiatives, the authors wrote, will help future researchers better understand the nuances of how such initiatives spread. The study’s data included some conservation sites that were abandoned, so one avenue for future research is to track the success of initiatives on an ongoing basis instead of just whether they are formally adopted.

The researchers hope future work will shed more light onto how conservation efforts go from proof of concept to actually preserving natural resources and protecting endangered species like the black rhino and so enable more of them to do so. After all, they wrote, “[t]he persistence of biodiversity and ecosystem services depends on the adoption of effective conservation initiatives at a pace and scale that match or exceed environmental threats.”

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!