June 6, 2019 — In 2007–08, the cost of fertilizer soared — driven in part by a 400% spike in the price of phosphate rock, a key ingredient. The shock especially hurt poor subsistence farmers, spurring protest and rebellion in Kenya, Vietnam, India, Nepal, Nigeria, Egypt and elsewhere.

But while crops need phosphorus to grow, mineral phosphate — concentrated in a handful of nations, leaving many dependent on the whims of international markets — isn’t the only source. A study published earlier this year in the journal Earth’s Future looks at how, by recycling phosphorus, countries could become less dependent on uncertain global trade while cutting down on pollution from fertilizer.

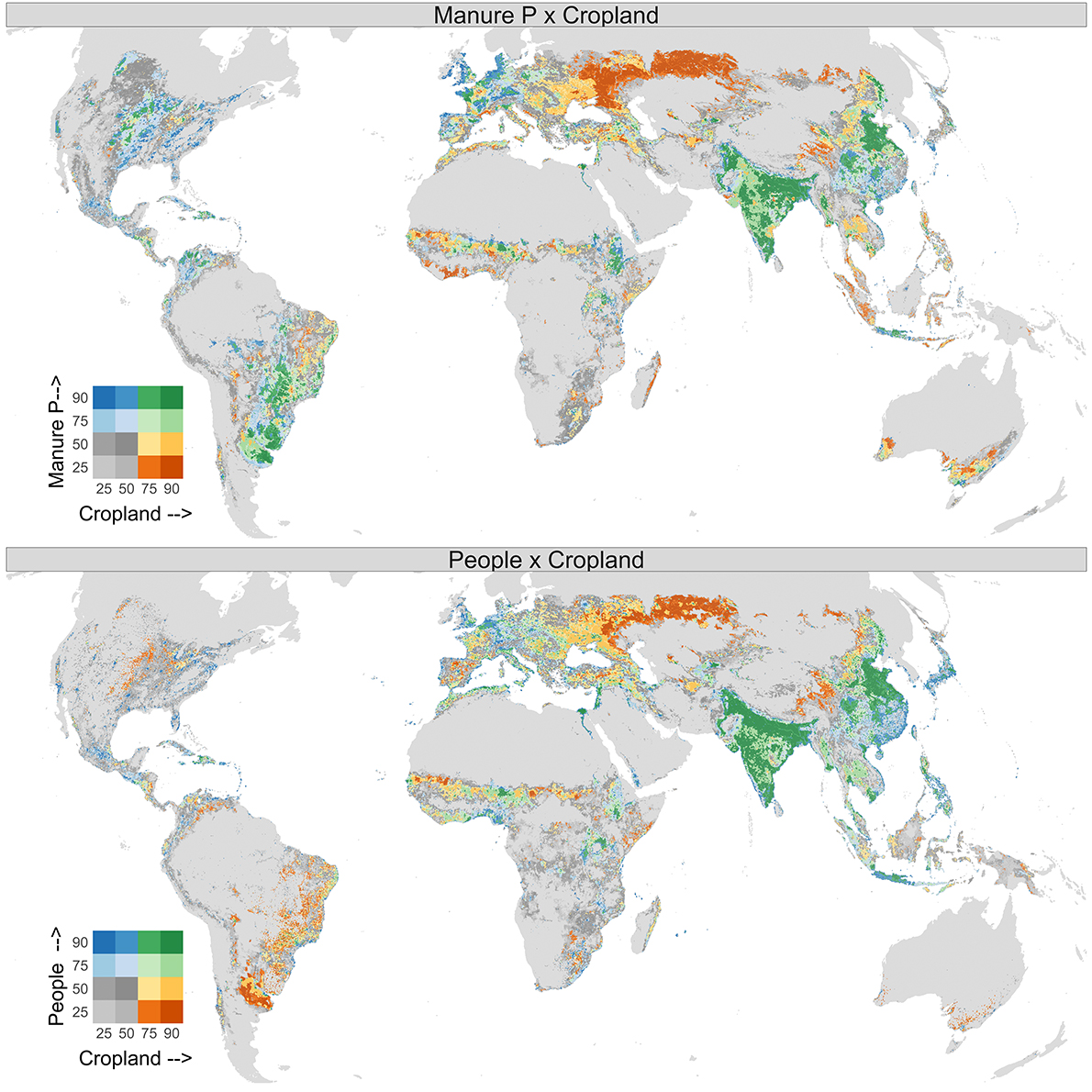

The international team of researchers sought to identify “hot spots” for recycling phosphorus. Since animal manure, human waste and uneaten food contain the element, the team mapped places around the world where crop production coincides with high densities of livestock or people.

Researchers mapped places around the world where crop production coincides with high densities of livestock or people in order to identify “hot spots” for recycling phosphorus. Photo courtesy of Stephen Powers. An edited version of this paper was published by AGU. Copyright 2019 American Geophysical Union.

Hot spots are on every continent except Antarctica. They tend to be in countries that rely on imported phosphorus to cultivate crops, or in nations where demand for fertilizer has grown substantially since the beginning of this century.

Hot spots for recycling phosphorus from sewage and food waste occurred mostly in China, India, Southeast Asia, Europe, Central Africa, East Africa and Central America. Those focused on using animal manure are mostly in China, India, Southeast Asia, Europe and Brazil. Roughly 70% of recycling hot spots are in countries in which the net import of phosphorus fertilizer accounts for at least 40% of the phosphorus fertilizer used.

Identifying places where phosphorus-laden waste products occur near agriculture could help nations develop local phosphorus recycling and contribute to “agricultural independence,” the researchers write. And phosphorus recycling can also have environmental benefits. Phosphorus from human and animal waste can end up in waterways, where it can spur the growth of harmful algae, so keeping it out is beneficial.

By developing ways to efficiently recycle phosphorus, countries reduce water pollution at the same time as they build food systems less prone to price shocks.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!