June 28, 2022 — Think about the last time you went to the grocery store. Maybe you bought a gallon of milk, a carton of strawberries, a box of granola bars, a jar of peanut butter. Each of these food or beverage products likely came in plastic or glass packaging. Humans have become heavily reliant on packaging for two key reasons: convenience and safety. Doing so has had huge implications for the environment — from the carbon-emitting fossil fuels used to make packaging to the habitat-harming trash it becomes when we’re done.

Which is why many consumers and producers are looking for “sustainable alternatives” to lessen the harmful impact on our planet. Between 2016 and 2020, Google searches for sustainable goods increased by 71%. But can packaging really be sustainable? Well, it’s more nuanced than you might think.

Glass vs. Plastic

The Oxford English Dictionary’s definitions of “sustainable” include “capable of being maintained or continued at a certain rate or level” and “designating forms of human activity (esp. of an economic nature) in which environmental degradation is minimized.” The question of what constitutes sustainable packaging often focuses on two common materials: glass and plastic. Plastic has been demonized in recent years due to its origins in fossil fuels and its finite life in a recycling plant. Images of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch often depict piles of single-use water bottles and other plastic debris floating in the ocean.

Many consumers consider plastic an unsustainable option, in part because of how much of it ends up in landfills or in nature. Photo courtesy of United Nations Development Programme in Europe and CIS from Flickr licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Given these myriad issues associated with plastic and plastic waste, many consumers think of glass as a safer, more sustainable alternative. Glass can be recycled indefinitely without degrading. Surely it is better for the environment, right?

Unsustainable Glass?

Despite the common assumption that glass outweighs plastic in environmental benefits, some recent life-cycle assessments (LCAs) show a more complicated story.

In 2020, researchers at the University of Southampton looked at the relative environmental impacts — from raw material extraction through use and final disposal — of glass and plastic used in beverage packaging. The LCA assessed 1-liter (1.06-quart) beverage containers into three categories: fizzy drinks, fruit juice and milk. It examined glass bottles, aluminum cans, milk cartons, Tetra Pak, and two types of plastic bottles, polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE).

Although glass can be recycled indefinitely without degrading, it has its own environmental issues. Photo by jasper benning on Unsplash

The assessment focused on 11 “impact categories” within the three beverage groupings, ranging from eutrophication to global warming potential to toxicity for humans. The glass bottle had a higher negative impact than the typical packaging alternatives for each beverage across nearly all impact and beverage categories.

An older LCA, published in 2014 in The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment by researchers from GE and LCA consultant EarthShift, compared glass and plastic bottles for holding contrast media used in X-ray procedures. The LCA suggested that the plastic bottle had lower environmental impacts across all designated impact categories, including greenhouse gas emissions, impact on ecosystems and impact on resources. Adding in the impacts of the packaging containing the bottles yielded less clear results, however.

Also in 2020, researchers in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Politecnico di Milano in Italy published an LCA comparing reusable glass bottles to single-use glass bottles. The LCA concluded that the refillable glass bottle is “by far preferable” to the single-use glass bottle. However, as the study notes, the distance a refillable bottle travels affects how well (and, at large distances, whether) it has a lower overall environmental impact than the single-use option.

According to Packaging Sustainability author Wendy Jedlička, the weight of glass has a heavy impact on its carbon footprint. In the United States, the manufacturing of glass and glass products was responsible for 15 million metric tons (16.5 million tons) of carbon dioxide equivalent greenhouse gases in 2018.

Is Plastic Any Better?

While these LCAs may have surprising conclusions about glass for some readers, writing previously in Ensia, freelance writer Karine Vann noted, “[LCAs] tend to privilege the impacts of production (which, for example, materials like plastic score well on because they are lightweight and low-carbon to produce) over the impacts of disposal (a measure for which, being difficult or impossible to recycle, plastics score poorly).” One study found that 79% of plastic ends up in a landfill or in nature, potentially harming wildlife. And according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, in 2018 just 2 million tons (1.8 million metric tons) of plastic containers and packaging were recycled — 13.6% of the amount generated that same year.

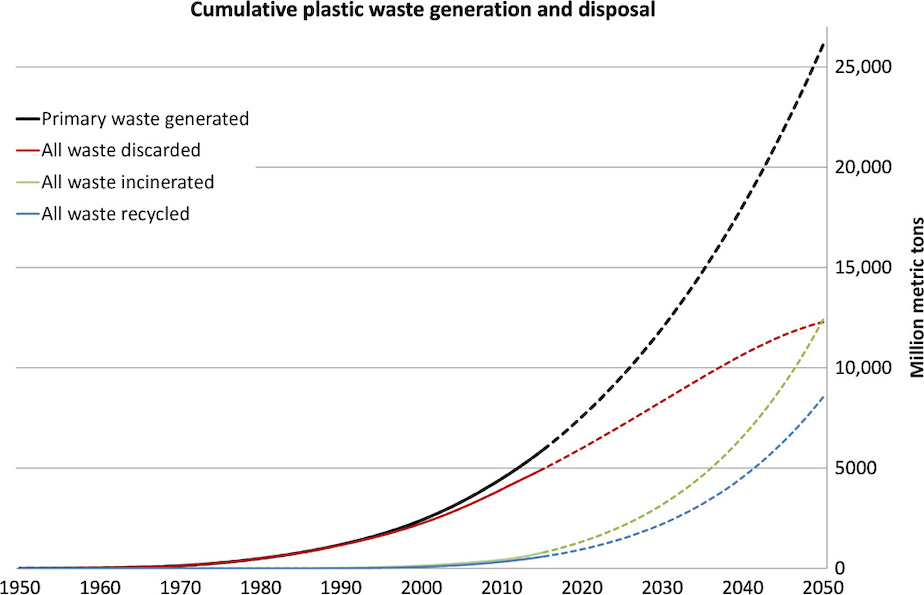

Cumulative plastic waste generation and disposal (in million metric tons). Solid lines show historical data from 1950 to 2015; dashed lines show projections of historical trends to 2050. Copyright © 2017 The Authors, “Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made,” some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 4.0 (CC BY-NC). Click image to expand.

Beyond that, the chemicals that make up plastics can pose their own health risks to humans. Nearly two decades ago, Scott Belcher, a research professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at NC State University, and colleagues found that bisphenol-A (BPA), a chemical that serves as a building block for certain plastics, can disrupt the function of hormones, interacting with estrogen receptors. BPA also has been associated with alterations of cells of the nervous system during development and with heart arrythmias.

Although many plastic products for sale today are marketed as “BPA free,” that doesn’t mean they are free of harmful chemicals. “The question that consumers need answering is, ‘What’s being used instead of bisphenol-A?’ And this gets to this idea of regrettable substitution,” Belchers says. “A lot of these substances look chemically a lot like BPA. There’s BPS [bisphenol-S], BPAF [bisphenol-AF] — all of these other bisphenols can have similar or even more activity than BPA. And because the specifics of their use are often hidden as confidential business information, we don’t know how — or how widely — substituted chemicals are used.”

And BPA and its substitutes aren’t the only chemicals found in plastic packaging. Belcher also expresses concerns regarding PFAS chemicals, which are commonly used in takeout boxes, microwave popcorn bags and other food packaging materials that repel grease. And flame retardants, colorings and other materials go into plastics as well.

Jane Muncke, environmental toxicologist and managing director of the Food Packaging Forum, a nonprofit organization focused on chemicals in food packaging, has found that potentially harmful chemicals can move from plastic packaging to food due to four main factors: temperature, storage time, type of food and materials used in the packaging.

Through years of study, researchers have been able to determine that various chemicals found in plastics are associated with adverse health effects, such as cancer, infertility, diabetes, obesity, neurodevelopmental issues, immune system problems and asthma. “Exposure to hazardous chemicals contributes to premature mortality and to increased chronic disease,” says Muncke.

“[The] ideal that we’re shooting for is to get rid of the chemicals that impact your body,” Belcher says.

Beyond Packaging

All that said, Muncke suggests the big sustainability issue with food might not be the packaging at all, but the products themselves. She points to providing nonseasonal food products in the winter. “There’s always the example of organic cucumbers grown in December in southern Spain, where they’re pumping out fossil aquifers, nonrenewable groundwater aquifers, to produce organic cucumbers that then get flown to central Europe so that we have fresh cucumbers in December. And then, the argument is always ‘Yeah, well we don’t want to have food waste,’ so we shrink wrap it in plastic,” Muncke says. “Then people say it’s sustainable packaging. The point is that it is a product that is not sustainable. It doesn’t matter if you wrap it in ‘sustainable packaging’ or not, it’s a product that shouldn’t exist. People shouldn’t be making and buying that product.”

Some experts point to the products themselves, not necessarily the packaging, as an issue that should be dealt with. One such example is nonseasonal food. Photo © iStockphoto.com | Esben_H

Muncke calls for examining why we need certain products in the first place. “It’s kind of a straw man argument, it’s like shifting the discussion away from where it needs to be,” she says. “How do we produce, how do we consume foods, and then, once we’ve clarified how that should be happening we can talk about how to package them.”

Still, Muncke says we can’t change the entire economy and stop shipping fresh vegetables across the globe without a transition. So, as a tool for those in the food business who deal with packaging decisions, Muncke and industry, nonprofit and technical partners developed the Understanding Packaging (UP) Scorecard, which helps businesses reduce the adverse health and environmental impacts of food packaging and containers. The scorecard compares packaging across six categories: climate impact, water use, plastic pollution, chemicals of concern, recoverability and sustainability of sourcing — with the goal of transitioning to more sustainable systems.

Culture Is Key

Sustainability in packaging requires not only systems thinking but also a consideration of culture, says Packaging Sustainability author Jedlička. Systems thinking takes a holistic approach that brings together different elements of society, such as people, the economy and the environment. In packaging design, systems thinking looks at addressing human needs while also considering impacts to the planet.

Including culture into a systems thinking methodology makes for a more useful tool, Jedlička says. For example, she notes that for years train passengers in India would drink chai tea out of unfired clay cups, then toss the cups out the window to the side of the tracks, where they would degrade. When plastic cups were introduced the habit continued, littering the landscape.

“I can look at a list of [materials] and go, ‘Yeah, that’ll work.’ But is that appropriate? Does it fit the community?… How does it fit into the bigger scheme of things?” —Wendy Jedlička

“Culture is really key,” says Jedlička. “That’s one of the things that the systems thinking methodologies don’t directly address. They look at profitability, which is great; they look at people, fair trade, and the environment, which is super important. But that culture aspect, that’s what makes everything else sink or swim.”

In other words, sustainability is based on the context. “I can look at a list of [materials] and go, ‘Yeah, that’ll work,’” Jedlička says. “But is that appropriate? Does it fit the community?… How does it fit into the bigger scheme of things?”

She offers The Beer Store in Ontario, Canada, as an example. In 2021 they collected 98% of the refillable glass bottles sold in their home province, reusing each 15 times on average. This system works because it has become part of the culture.

The Beer Store is one of many companies across the world that follows the “milkman” model, where packaging is reused. Loop is a global reuse platform that works with companies to help build a circular economy. It partners with retailers like McDonalds, brands like Coca Cola, and operational partners like FedEx to enhance adoption of multiuse packaging.

Whole System Thinking

The scope of sustainable packaging ranges far beyond the debate over glass versus plastic — a conversation that is ongoing — and there isn’t a universal sustainable packaging material. “There’s not one answer, and there’s not one optimal packaging type. I mean, glass is great, but paper is also great, and so are many other materials,” says Jedlička, “in the right context, and preferably as part of a closed-loop system.”

In the perspectives of Muncke and Jedlička, as important as the stuff our stuff comes in, is considering why we need a product in the first place and the culture in which it functions. Taking these additional aspects into consideration allows decision makers — both producers and consumers — to think more holistically about packaging and products, which is more likely to change the systems in which this all occurs, and, in doing so, contribute to finding packaging that is truly sustainable.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!