June 11, 2020 — In December 2008, Shubhendu Sharma, then an engineer at Toyota in the South Indian city of Bengaluru, attended a lecture that would change his life. Holding center stage was Japanese botanist and plant ecologist Akira Miyawaki, who had been invited to plant trees at the Toyota facility there to help offset carbon emissions resulting from its vehicle manufacturing process. This was part of Toyota’s Environmental Action Plan, the series of goals the company had set to eliminate carbon emissions from its vehicles, production and plants by 2050. Miyawaki described a procedure for growing trees that he had developed that could restore natural vegetation even on degraded land. He spoke of how planting seedlings of indigenous trees close together could speed growth, helping to solve a range of environmental woes.

For Sharma, just one phrase stood out: “one meter, one year.” The fact that a tree could grow an entire meter every year was a fascinating revelation, Sharma says.

“It can take hundreds of years for a forest to rejuvenate on its own,” he says. “But we don’t have that kind of time. Here, we’re looking at a methodology that converts a barren patch of land into a thriving forest in a span of three years. It was like a huge ray of hope. I felt like this is something that I should be doing for the rest of my life.”

The next year, Sharma volunteered to help Miyawaki establish his forests at Toyota’s campus in Bengaluru, and painstakingly documented the process as they planted 30,000 trees on a single hectare (2.5 acres) of land.

In 2011, Sharma launched Afforestt, a for-profit organization that shares the technique of building mini-forests across the world. Since then, the Miyawaki technique has been embraced by corporations, non-governmental organizations and even schoolchildren. So far, 285 such forests have been planted around the world, including 135 in India, says Sharma, created not only for carbon offsetting, but also to increase biodiversity, build habitat, protect shoreline, enhance aesthetics and enrich environmental education.

Improving on Nature

To achieve these many benefits is not simple. The Miyawaki technique brings together a spectrum of processes that must be followed with precision, from preparing the soil to managing a mature stand.

Identifying native vegetation that is adapted to the climate and rainfall of an area is the first step to creating a Miyawaki forest, says Sharma. Extensive surveys are required to identify the right species.

Also important is to plant species found in a mature forest. If you completely strip an area of its vegetation, Sharma says, grass is often the first type of plant to grow back, followed by pioneering species — shrubs and perennial grasses. Next are the shade intolerant species, usually shrubs and smaller trees that need lots of sunlight to thrive and lastly, the climax species that tolerate shade. These do not require full sunlight for optimal growth.

The Miyawaki technique bypasses the first two stages of growth — the grass and the pioneering species — and goes right to shade-tolerant climax forest species, “the most robust trees in any ecosystem,” Sharma says.

“This doesn’t mean that we’re tampering with nature in any way,” he says. “We’re merely speeding up the process to bring that forest back.”

In a natural forest, the soil is soft and permeable, allowing roots to penetrate easily. To re-create this and boost nutrients, Sharma says, the Miyawaki technique adds biomass such as coconut and paddy husks. Next, a microbial wash is brewed from forest soil mixed with cow dung and urine.

After the soil is treated, three to five saplings of indigenous trees are planted per square meter. Then the ground is covered with a thick layer of organic material. “The mulch protects the moisture content of the soil and prevents it from drying up,” says Shubhendu Sharma.

Positioning of different tree species relative to each other is key to a Miyawaki forest’s success. Photo courtesy of SayTrees

Shashank Sharma, project manager with SayTrees, a non-governmental organization that has planted 150,000 trees in India using the Miyawaki technique, says the positioning of the trees is key. He says that 1 acre (0.4 hectares) of Miyawaki forest contains 10,000 saplings, compared with 800 to 2,000 trees in a natural forest. And different tree species are intermingled in a way that lets their roots, which grow differently, efficiently occupy the underground space.

“We rotate between 60 native species,” he says. “Usually, a deciduous tree is planted alongside a fruit sapling, a floral shrub and a medicinal herb.”

In the first four to five years, Shashank Sharma says, the focus is on vertical growth. After some trees have obtained their maximum height, they expand horizontally, providing a canopy for smaller shrubs and shade-tolerant saplings that capture greenhouse gases as they fill in the understory.

“We’ve seen that carbon sequestration is better when the Miyawaki forest has these three layers — shrubs and shade tolerant trees, and then the canopy layer,” he says. Studies into carbon sequestration of these forests are ongoing, he says.

Unique Challenges

The Miyawaki technique can prove challenging because even minor mistakes can make the process labor intensive, incurring financial and other costs.

When mulching is not done right, for instance, the densely packed trees may need intensive watering. When the species selection goes awry, it can derail the entire process.

Sivakumar Shanmugavelu, one of the founding members of Ainthinai, a non-profit based in Chennai, tried the technique in 2017 to help restore degraded land in the outskirts of the city. He planted Indian beech, which usually grows on the banks of riverbeds. Because of a lack of groundwater, he says, the trees grew slowly, and many of them died.

Shanmugavelu changed tactics, planting trees of different species and varying heights. The trees attracted a rich array of other living things — nesting birds, bats, honeybees, snakes and lizards. “In just one year, I could see the difference,” he says.

Today, Ainthinai is planting Miyawaki forests in degraded shore areas of Chennai’s vast coastline, hoping that dense forests could act in the same way as mangroves — to stop the devastating effect of tsunamis or at least break the intensity of bigger waves.

Building Communities

Though it was established in Japan in the 1970s, the Miyawaki method was tested for the first time in 2000 in a part of Sardinia, Italy, where traditional reforestation had all but failed. Just two years later, dramatic increases in green cover were recorded and in 2011, studies revealed promising results in restoring not just the trees, but a rich biodiversity as well.

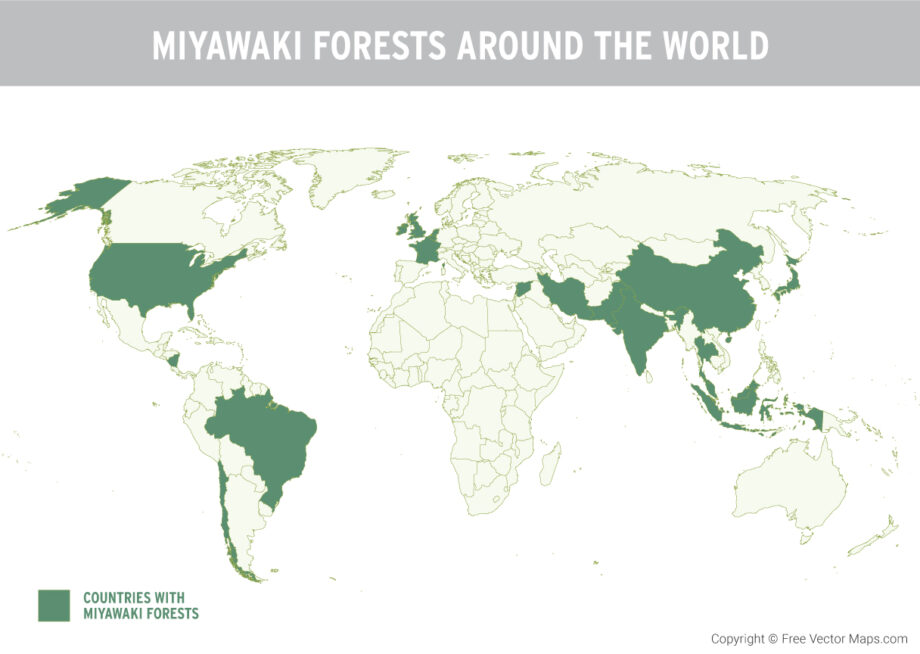

Today Miyawaki forests are thriving in countries around the world, including Belgium, the Netherlands, the U.K., Pakistan, Curaçao and France. In many, these forests are an exercise in building communities.

In the Netherlands, they’re called Tiny Forests, because they can be planted in a space the size of a tennis court. “A Tiny Forest … can grow in small, lonesome places in cities and towns, where it gives a helping hand to its biodiversity,” says Barry McGonigal, international director for LEAF with the Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE) in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Daan Bleichrodt, project lead at Tiny Forests in the Netherlands, says they’ve been working with Afforestt to create as many tiny forests as possible in urban areas. “We’ve planted 81 so far, and will plant at least 120 more,” he says. Bleichrodt says the projects aim to connect city dwellers, especially children, with nature.

Schoolchildren planted two of Belgium’s first Miyawaki forests, called “Tiny Forests,” in March 2020. Photo courtesy of GoodPlanet Belgium, 2020

“How can we expect kids who don’t grow up with nature to start caring about global warming, deforestation, plastic soup and climate change?” he asks. “And they may be the last generation to be able to stop this.”

Forests they plant are adopted by schools in the Netherlands that follow the Tiny Forest Ranger curriculum. Teachers take kids ages 6–12 outdoors once every month for a lesson about every aspect of the growing forest.

“Learning in such environments can have a powerful positive effect,” says McGonigal.

Casper Ohm, marine biologist and chief editor at Water-Pollution.org.uk, applauds the Miyawaki forest concept’s multiple benefits. “Given the current state of the environment, it could really save polluted cities,” he says, “and help offset carbon emissions all over the world.”

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

Thanks for the details.

So, as an average Indian, if my Carbon footprint is 3 Tons per year, how many miyawaki trees I would need to offset it ?

e.g. While searching on Google, found that 1 fully grown normal tree with around 100 years of life = 21 kg of CO2 offset per year.

Thanks,

Vinit Swadia