October 24, 2019 — When she was about 8 years old, Judy Elson received a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle from her great-aunt that featured North American birds. Her relative had a passion for feeding backyard birds, and Elson has carried on the tradition for the past 30 years, in turn passing on her enjoyment and dedication to her own children. “They put together the same jigsaw puzzle I did as a child and started recognizing birds even before they knew they were interested in them,” she says. With 12 feeders in her garden in Cary, outside Raleigh, North Carolina, she observes about 50 birds per day from up to 22 different species. “I feed the birds to benefit them, but it also brings them in closer to where they are easier to see,” Elson says. “Most of my feeders are outside a bay window in my dining room where I can sit and watch the birds. That is so enjoyable and relaxing.”

Backyard bird feeding is one of the most common ways people engage with wildlife in many parts of the world. Estimates show that about half of households in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia feed birds. In Great Britain, homeowners provide enough food to support approximately 196 million birds.

While people have always fed birds with kitchen scraps and homemade feeders, the practice has substantially changed since the 1950s with the increased commercial availability of diverse bird foods and feeders, making it easier to attract a greater number of bird species to backyard gardens year-round.

Researchers are just beginning to understand the ecological impacts, positive and negative, of this massive human intervention. From helping birds survive the winter to boosting bird populations and reproduction, feeding is reshaping bird communities and behaviors and even altering migratory patterns.

A 2019 study led by researchers from the British Trust of Ornithology found an increase in the diversity of birds visiting garden feeders in the past 40 years in Britain. The study, based on data recorded by citizen scientists for the Garden Bird Feeding Survey, shows that “approximately half of all birds using feeders belonged to just two species in the 1970s, but by the 2010s, the number of species making up the same proportion of the community had more than tripled.” For example, according to Kate Plummer, a research ecologist with the British Trust of Ornithology and a lead author of the study, just 10% of volunteers saw wood pigeons and goldfinches at feeders in the 1970s, but now these two species are common visitors in close to 90% of gardens. After significant declines between the mid 1970s to the mid 1980s, the goldfinch population has more than doubled between 1990 and 2015.

“We think it is the use of feeders that is in part driving these levels of increase,” says Plummer. “In the 1990s, bird food companies targeted goldfinches and started producing finer seeds, which made it easier for the birds to get what they needed in gardens.”

Bird food provided in British gardens has also affected the Eurasian blackcap, which has evolved a new migration strategy. For the past 60 years, blackcaps are more often choosing to spend the winters in Britain’s urban areas rather than migrating to the Mediterranean as they used to. A study concluded that milder winters combined with increased bird feeding have contributed to the change. “Feeding is causing species to adapt and evolve,” says Plummer, who also led this research.

It’s not just in Europe that birds are taking advantage of people’s feeding activities in their gardens. In 2017, Vancouver, Canada, residents elected the Anna’s hummingbird as their official city bird. Described by the city as “classy, urbane and stylish with the heart of a tiger,” the tiny bird now helps the city build awareness of birds in the urban environment.

Vancouver, Canada’s official bird, Anna’s hummingbird, is a relative newcomer to the city since its winter range expanded more than 435 miles in the past two decades. Photo courtesy of Becky Matsubara from Wikimedia, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Yet, Vancouver’s favorite bird is a relative newcomer to the city. In the past 20 years, Anna’s hummingbirds have expanded their winter range northward by more than 700 kilometers (435 miles). A study based on long-term data from Project FeederWatch, a citizen science program in the United States and Canada led by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies Canada, found that the hummingbirds are now able to survive farther north in colder locations in part because more people are providing nectar feeders and planting exotic flowers in their gardens that bloom in different seasons, including the winter.

“It was quite rare to find an Anna’s hummingbird in the winter north of the California border 20 years ago,” says David Bonter, avian ecologist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and one of the study authors. “Most of those birds can handle cold temperatures as long as they have something to eat, and more individuals are surviving winter in places where they could not have previously,” he adds. “What surprised everybody involved in the study is how quickly it happened.”

Birds aren’t the only species impacted by human feeding. In Australia, flying foxes have changed behavior based on their ability to find food in urban areas. Photos © iStockphoto.com/phototrip

The impacts of human feeding extend beyond birds. For example, in Australia, flying foxes are increasingly living in urban areas because they can easily access food all year. People choose to plant native and exotic plants that flower in all seasons, which entices the bats to spend more time in those locations.

While feeding animals can in some cases lead to increased survival and breeding success, there can be negative consequences as well. For example, a 2019 study of the impacts of human feeding on a group of bottlenose dolphins in Western Australia found that, while other factors may have also played a role, both calf survival and female reproductive success were negatively affected by feeding.

Up for Debate

Backyard bird feeding is the subject of extensive debate. For example, what are the long-term ecological consequences of changing the migratory behavior of birds? “The amount of human food supplied every single day is gigantic, and that genuinely has had a massive effect on the overall environment and the population of birds,” says Darryl Jones, author of The Birds at My Table: Why We Feed Wild Birds and Why It Matters.

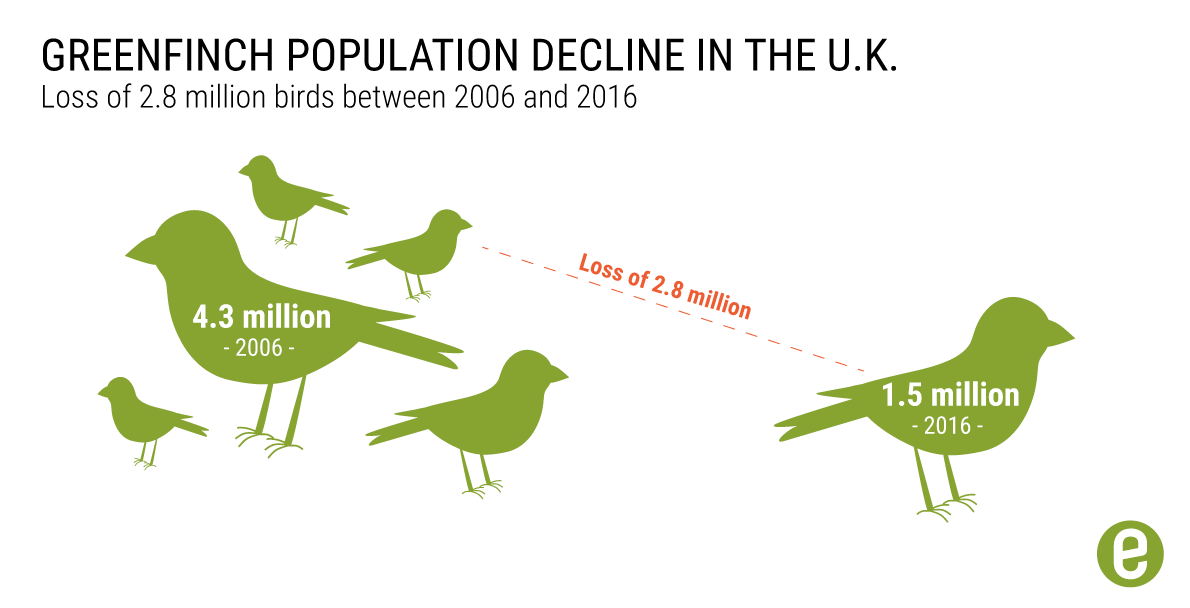

For example, in a 2018 article, scientists raised concerns about the risks associated with increased disease transmission. Garden feeders can indeed spread disease by bringing birds into contact with species they would not otherwise interact with. Risks can be higher if feeding stations are not cleaned on a regular basis, allowing food waste and droppings to accumulate. The number of greenfinches in the UK declined from a peak of about 4.3 million in 2006 to about 1.5 million individuals in 2016 after a disease outbreak that researchers hypothesized could be due to feeders. In the eastern U.S., bird feeders facilitated the transmission of an eye infection that decimated the house finch populations in the 1990s.

A paper exploring the impacts of wildlife feeding on migration and disease suggests that one of the benefits of migration is that it allows animals to leave habitats where parasites have accumulated and eliminates infected individuals that cannot survive the journey, and so can reduce parasite infection in populations. “Staying in one place increases exposure to infection,” says Richard Hall, an assistant professor at the Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia and co-author of the paper.

Feed Responsibly

According to Hall, the implications of bird feeding are also complex, and while feeders can facilitate the spread of diseases, they can in certain cases help improve bird condition.

“When you feed birds you aggregate them and that increases the transmission of parasites, but if you are feeding the right kinds of food it also means they can have a better immune function so even if they come in contact with another sick bird or parasite in the environment they may be better equipped to fight off an infection,” he says, “so there is a balance there.”

When done responsibly, backyard bird feeding can help birds and also offers people a personal connection to nature. Photos © iStockphoto.com/JJPaden

If done responsibly, many researchers say, feeding can help populations in need, especially in winter, and increase biodiversity conservation. “What we do as humans tends to have a negative impact on wildlife, and many of the species using garden feeders like goldfinches were negatively impacted by the intensification of agriculture. That’s why they were in decline, but now we are putting feeders and they are increasing,” says Plummer. “If we can compensate in some way for other negative effects we are having on some of these species, it feels like we are doing something beneficial.”

Backyard bird feeding also plays an important role in establishing personal connections with nature, with benefits to human health and well-being. “As we are more and more in big cities where nature is becoming rare and more difficult to encounter, bird feeding is a desperate search for some connection with nature. If you put a feeder in your garden, truly wild animals will come and visit you,” says Jones. “It is an extraordinary experience.”

The direct observation of the natural world can also get people to be more supportive of conservation efforts. “There is value in that human interactions with backyard birds make people realize the birds are in trouble, and we need to make more efforts to conserve what’s left,” says Bonter.

A 2019 study that surveyed participants of Project FeederWatch in the U.S. to understand the connection between people’s emotions and what they observed at bird feeders, found that most people who directly observed a problem at their feeders, such as the presence of a cat or sick birds, reported they would take action.

“There is a high percentage of people who do something in response to what they see,” says lead study author Ashley Dayer, an assistant professor of human dimensions in the department of Fish and Wildlife Conservation at Virginia Tech. “People are doing a lot more than just the feeding itself. They are managing the predators out there, they are cleaning the feeders, they are taking a lot of actions.”

In Australia bird feeding is strongly discouraged, even though the proportion of people feeding birds is the same as in the Northern Hemisphere. “People are strongly motivated to feed birds and care about them, but they are doing so in the complete absence of any information or advice and don’t know how to do it properly,” says Jones, who just published a book, Feeding the Birds at Your Table, to advise people how to feed birds responsibly.

Backyard bird feeding can have benefits as long as it is done correctly, and a number of resources such as Project FeederWatch provide guidelines and steps people can take to create a safe feeding environment for birds, such as frequently cleaning feeders, spacing them far apart from each other to reduce exposure to disease, providing nutritionally appropriate foods, planting native species or recording data to allow scientists to better understand bird populations. With a recent study published in Science revealing that bird populations in the United States and Canada have fallen by 29 percent since 1970 — even species “once considered common and wide-spread” — people may become even more motivated to put out feeders to help birds, so making sure it’s done correctly will be important.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!