March 26, 2013 — When Susan Stevens’ young son went into anaphylactic shock in 2006, she rushed him to the emergency room as her thoughts raced: Was it something he ate? Something he touched? Turns out a cashew caused the severe reaction, but she learned he had other severe allergies, leading her to completely reevaluate her family’s lifestyle choices. Stevens became adept at reading labels and selecting chemical-free cleaning products, and adopted other practices, such as removing shoes at the door to improve indoor air quality. She began blogging about her eco-friendly lifestyle, had her home renovated green and started night school for sustainable design. What started as a personal epiphany was becoming a passion to encourage sustainable behaviors in others. But how could she make a bigger difference?

In 2010, Stevens launched Practically Green, a business that uses game techniques to encourage people to complete simple actions as a path to collective environmental change. She was at the forefront of the emerging strategy called “gamification,” rooted in decades of social psychology research. Gamification uses games and social media to motivate behavioral change by tapping people’s instincts to follow social norms and to compete. In fact, marketing and business executives have used tools from social psychology to influence behavior for decades. In the 1990s, BJ Fogg pioneered the study of how technology can be used to influence behavior. His once-controversial research now garners millions of dollars for companies. “Persuading people through technology is the next social revolution,” Fogg, now director of the Persuasive Technology Lab at Stanford University, said in Fortune Magazine.

But can it be used to save the planet? Stevens thinks so.

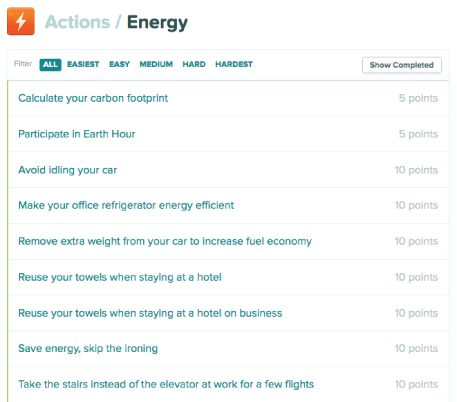

Players compete for points and earn badges by completing suggested environmentally friendly actions in four categories: energy, water, health and “stuff.”

Before she started her business, Stevens had noticed how much time people spent on social media and on games like FarmVille and wondered, “What if people were doing things that matter?” But it wasn’t until she took a class on the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED program, where buildings receive one of four levels of certification by earning points for various actions, that her pondering solidified into something concrete.

“I kept thinking, ‘Why isn’t there something like this for people?’” Stevens recalls. So she developed a point-based program modeled after LEED, but for daily life. Players compete for points and earn badges by completing suggested environmentally friendly actions in four categories: energy, water, health and “stuff.” Every action includes links to additional information, such as a database that contains details about various cosmetic products.

Stevens launched Practically Green at the inaugural SXSW Eco conference in Texas in October 2011. Just a year later, her clients include Seventh Generation, which uses the program to encourage employee sustainability, and NBC Universal, whose Practically Green–based app, “One Small Act,” is available from iTunes. Anyone can play Practically Green online at no cost—and tens of thousands do.

Keeping up With the Joneses

Although people often insist they are not influenced by others’ behavior, social scientists know better. In a well-known 2008 study, Arizona State University professor emeritus of psychology Robert Cialdini found hotel visitors were most likely to reuse towels when a placard stated that most of the occupants of a guest’s room reused their towels—even though each guest in a room has nothing in common with previous or future guests of that room. Messages listing the hotel average for towel reuse, or appealing to a sense of environmental stewardship worked less well in promoting towel reuse. Cialdini’s principle of influence, called “social proof”—what some think of as peer pressure or following norms—is central to gamification.

“When two, three, four, 10 people start to do [something], it starts to get all the people around them to do it, and then it goes over the tipping point and becomes the norm.” — Susan Stevens

“People tend to change over sustainability when the social norms change,” Stevens said at the “Why Should I?” panel discussion at the 2012 SXSW Eco conference. “When two, three, four, 10 people start to do [something], it starts to get all the people around them to do it, and then it goes over the tipping point and becomes the norm.” For people to act in a particular way—to recycle or carry a water bottle—the norm does not have to be across society, but can be within a company, neighborhood, school or group of friends. It can even involve a “granfalloon”-type group, such as residents of the same hotel room.

In gamification, behavior is driven not only by social proof but also by competition. Several companies using Practically Green have employee teams that compete. “It’s hysterical,” Stevens said. “Every week when the ranking comes out, you see a massive flood of people in the group on the bottom that’s coming in to start to make more points. So it works.” She adds that the team aspect boosts participation in folks who might not otherwise want to play because they would feel they let down the others if they didn’t join in.

Since Stevens launched Practically Green, similar companies have emerged. Badgeville uses games, analytics and social networking to influence customer and employee behavior for more than 200 companies, from Dell to Panera Bread to Mother Nature Network, though only a small portion of their clients address social responsibility. Grant Williard launched an updated version of his JouleBug app, which encourages sustainable living activities such as water and energy conservation, recycling and other actions, at the 2012 SXSW Eco conference. Williard says he envisioned the app after using an online carbon footprint calculator that measured the impact of his lifestyle on the environment and getting an “awful score.” That led him to research how to reduce his carbon footprint. “I got a laundry list of tips, but they weren’t applicable,” he says. “It was winter and they were air conditioning tips.” He decided to create something bite-size.

©iStockphoto.com/V2images

“The only way to get people motivated is competition. So that’s when we came up with the idea of making it social, mobile and gameful,” Williard says. “When you’re on the subway on your way to work or you are standing in line, pulling out something like this that’s made to take 30 to 45 seconds of your time, that’s how we feel people will engage with sustainability.”

JouleBug provides reminders at particular times of day for appropriate actions—such as turning down your thermostat right before you leave for work (and the app can sync with a player’s utility company). Williard recently launched a business side to his consumer app, which sells universities, businesses, cities and other communities the right to use the app to encourage collective changes.

Getting to “Want To”

One of the groundbreaking aspects of gamification is that it bridges the gap between knowing and doing. Among the biggest misconceptions about promoting environmentally responsible behavior is that if people just knew about issues, that knowledge would compel them to change. This “deficit model” of communication—which says that giving people more information will change their view—has been widely discredited in recent years.

“If educating people about an issue would solve the problem, we would have no obesity and no smokers in our country,” said Lee Ann Head, vice president of research from Shelton Group, at the panel. Shelton, a marketing firm specializing in sustainability, found a conflict between values and actions in its annual Eco Pulse survey of American consumers.

“Two-thirds of American consumers say that conserving water is important to them and that they are concerned about the freshwater supply in the U.S.,” said Stevens. “When we ask about their activities … less than one-third have done anything in terms of changing their water habits—gardening or lawn practices or buying a water-efficient fixture for their home.”

So what changes behavior? “The first thing we think you need to do is wake someone up to their unconscious behavior,” Head stressed. “You have to make them feel a little uncomfortable about it, especially if they have an attitudinal belief that what they’re doing is wrong.”

Using this line of thinking, Shelton Group developed a series of Wasting Water Is Weird public service announcements featuring Rip the Drip, who shows up just in time to embarrass a person unconsciously wasting water. The PSAs aired about 24,000 times on 290 TV stations in more than 120 markets and received more than 150,000 views on YouTube, according to Penny Kemp, vice president of account management at Shelton. Through its Eco Pulse survey the company also found that nearly one-third of people who saw the PSAs were moved to change their water-use habits. This subtle shame—revealing to people that they are not following the accepted norm—is inherent in Cialdini’s social proof principle.

“It’s not about telling [people] that they’re wrong, as that never works. They are just not thinking about what they’re doing,” said Head. “You have to do it in a lighthearted and fun way so that you make a problem visual. And then you have to give them some prescriptive things to do. It’s got to be simple and it’s got to be easy.”

This screen shot from Practically Green shows how environmentally friendly activities translate into points players can use to compete with each other.

Robin Krieglstein, senior producer of Badgeville, agreed. “We don’t realize over the course of a week or a month we even do some of these behaviors,” he said at the panel. “If you actually begin to track how many times people are doing a behavior, then you can set clear goals, like trying to turn off the water while brushing.” Games offering congratulation messages, badges and scores encourage people to continue their efforts, and Krieglstein said research shows that a “congratulations” in a game provides a similar effect in the brain as if it were spoken aloud by a person.

But Does It Work?

Head says it’s not necessary to make people believe in climate change or be concerned about other environmental issues to make them take action. “I don’t care about their motivation, I don’t care that they do it for the right reason,” she said at the panel. “I want to figure out what their motivation is, tap into that and get them to act. What matters is the end result.” If the motivation is simply competitiveness, then so be it.

But does it work? Preliminary results suggest yes. Above and beyond behaviors users already engaged in, in just two years Practically Green online has encouraged 1.7 million environmental actions and saved 1.5 million gallons of fuel, 57 million gallons of water and 269 million pounds of carbon dioxide, according to Stevens.

“People want to take steps and actions when it’s smart for them, when it’s practical, and helpful,” said Stevens. She says gamification works by using the best behavioral science has to offer to motivate people to become sustainable—and it only takes a few minutes per day. “Not a single client says a few minutes a day focusing on sustainability is time wasted.” ![]()

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2013 print issue of Ensia.

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

But policy makers and companies respond most quickly to the "will of the people". And most people don't just wake up one day and decide they need elected officials who will support a carbon tax or that they won't buy a washer that makes them push a button to turn off heat dry rather than making air dry the default for all washers. It's a journey to get people from "huh, I should do this" to "why is this so hard" to "there has to be a better solution". If game-based learning programs can help engage people to living and thinking in more conscious ways, I think they are a critical component of the grander solution we need.