June 20, 2019 — Earth frowns. With a face of green and blue, the planet’s mood is blue, too — as unblinking eyes cast a somber stare.

Colored with crayons, this drawing is the schoolwork of Maya, a fifth grader from the United States. At the top sits a title: “Greenhouse Gas Effect.” Piercing Earth’s atmosphere, sharp arrows represent solar radiation, which for the most part remain trapped as heat by a ring of gases aptly shaded green. While a patchwork of flags from around the world makes for a vibrant backdrop, it can’t detract from the dismal mood. To punctuate the point with urgency, there’s a red explosion with all caps in black: “EXTREME!”

Even the sun seems sad.

Kids like Maya are growing up in a world set to face the worst of climate change. As dire warnings pour out from research scientists and indigenous peoples around the globe, many U.S. teachers don’t mention our planet’s fever in the classroom — and think tanks and fossil fuel companies that deny the scientific consensus on climate promote junk lessons to instructors who do.

Artwork on the website Kids Against Climate Change shows various interpretations of students’ understanding of climate change. Image courtesy of Kids Against Climate Change

Yet the education system, like the climate system, is complex. Across the country, from elementary to high school — and from science class to social studies — other teachers are taking the initiative to tackle climate change and other environmental challenges. Middle schoolers in Hawaii survey residents about sea level rise. High school students in Oregon, with help from their teacher, advocate at the state capitol. And elementary kids in New York pick up crayons to illustrate the greenhouse effect.

Reputable Sources

Maya’s diagram is featured on the website Kids Against Climate Change. The site is run by Kottie Christie-Blick, a teacher at Cottage Lane Elementary School, a public school in New York state. Christie-Blick says students can begin learning about people’s negative impact on the environment by later elementary school.

“Teachers are experts at translating the adult world to the child in a way a child can handle,” says Christie-Blick, who plans to soon move from classroom teaching to work full time helping other teachers incorporate climate change into their curricula. Even with young students, teachers lead fire drills, discuss “stranger danger” and prepare for the possibility of school shootings. Those issues, she says, are “much scarier to our children than the changing climate.”

For Christie-Blick, teaching climate change is a lens to teach younger students about Earth’s systems, a required topic in New York’s state science standards. Students watch videos, draw pictures, visit websites like NASA Climate Kids, go on a field trip to a recycling center and participate in hands-on activities. In one of her lessons, Christie-Blick says, children place ice above mountains on miniature plastic worlds — then watch as the ice melts, filling up the basin below and flooding the tiny town. This year, her class even took a bus two hours north to meet with a state representative about climate change.

“I do get children who say, ‘My father or my uncle says they don’t believe [in climate change],’” Christie-Blick notes, explaining that in these situations, dozens of ears perk up, waiting to hear how she’ll respond. She says she explains to students that it’s about science, not belief, and that she uses only reputable sources of information such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

For years, Christie-Blick has been involved in the NOAA Planet Stewards Education Project, a federal initiative promoting environmental education. She attended webinars with climate researchers and then completed an action-oriented recycling project with her students.

Under the Trump administration, many federal agencies have deleted information about climate science from their web pages. But NOAA’s educational projects, including Planet Stewards and the Climate.gov website, remain online. So does the Climate Literacy and Energy Awareness Network (CLEAN), funded in part by NOAA and the National Science Foundation. It features about 700 ready-to-use learning activities, experiments, videos and visualizations vetted by teachers and scientists.

Teaching Environmental Problem Solving

Before she founded a school in Hawaii, Victoria Newberry left teaching — not once or twice, but three times. While she kept circling back to the profession, she couldn’t stand rote learning and textbooks. “I didn’t feel any connection to the real world and the problems that kids would have to solve,” she says.

That changed in the early 1990s, when she attended a five-day workshop on a new skills-based teaching method called Investigating and Evaluating Environmental Issues and Actions (IEEIA). In the method, developed by teacher educators from Illinois, students choose environmental challenges, investigate them, collect data and propose solutions.

Newberry became a full-time teacher again, using the curriculum for years in a public school on the Hawaiian island of Molokai. A study in the Journal of Environmental Education reported that in 2001, students whose classrooms used the curriculum knew more about ecology and the environment, and scored higher on tests of critical thinking, than those who did not. But Newberry says that after Congress passed the No Child Left Behind Act, mandating more standardized testing in public education, her school’s administration ended the program.

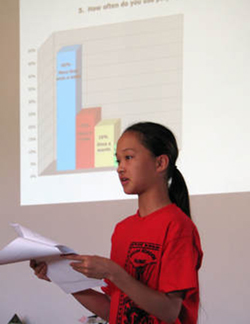

As part of the curriculum at Aka`ula School, students select a local environmental issue, write research questions, collect data and present their findings. Image courtesy of Aka’ula School

Rather than stop teaching with IEEIA, Newberry left the public school system. In 2003, she teamed up with Dara Lukonen, another teacher who used the method, to found Aka`ula School, a private school rooted in the model. Each year, fifth through eighth graders work in small groups to select a local environmental issue, write one or more research questions, and gather data — usually by surveying people on the island about their knowledge and opinions, but sometimes by collecting physical data like water samples. Then they present their findings to, and take questions from, as many as 200 community members.

Student projects have run the gamut of issues: water quality, feral cats, fishing licenses, landfill waste, public bathrooms and more. A few projects have addressed the climate.

“Climate change is a local issue for us,” Newberry says, since rising ocean waters pose a “serious threat” on Molokai. This year, one group of students investigated what residents know about sea level rise and whether they support the state’s recommendations for adapting to it.

Nearly 80% of Aka`ula School’s students are Native Hawaiian, according to Newberry, and researchers and teachers say that part of IEEIA’s success has been its compatibility with students’ cultural values. Peer collaboration syncs with the emphasis traditionally placed on community, while the environmental focus embodies mālama `aina, a traditional Hawaiian concept that Newberry says entails care for the land and sustainability for the future.

“It is not an easy curriculum to teach,” Newberry says. “It is much easier for a teacher to pick up a textbook and say, ‘Read 20 pages and answer 10 questions’ than it is to trust your kids to do the work. But it is so rewarding if you give it a try.”

Research shows that the kids tend to agree. “As young students we feel we have a lot to offer, and we know we can make a difference,” wrote Hina Chow, an eighth grader at the time, in a 2017 school newsletter.

Social Studies and Language Arts

That drive to take action is common in climate change education. “If I’m going to help them understand that there’s a problem,” says Christie-Blick of her elementary schoolers, “I have to help them feel that they have some control and they have some power to do something about it.”

On climate, the urge to do something can get political — fast. While lawmakers in some states are pushing to limit climate education, citing fears that teachers are trying to “indoctrinate or influence students,” other professionals argue that properly teaching about the climate crisis leaves educators with no choice but to dive into the politics, shifting from “climate literacy” to “climate justice.”

Tim Swinehart, a social studies teacher at Lincoln High School, a public school in Portland, Oregon, has taken class groups to advocate for climate action at the state capitol. He also worked alongside young climate activists to push the Portland school board to pass a resolution banning materials that cast doubt on the reality of global warming — and encouraging climate change curriculum in the classroom.

“I’m often mistaken as a science teacher because I teach about climate change,” says Swinehart. His classes are geography and — now that the resolution has passed — environmental justice. While students and teachers are advocating that the school district more fully implement the climate resolution, he does have enough support to engage students in climate activism.

But not everywhere is Portland. Since few teachers are able to “get their students out of the classroom and into the movement,” Swinehart says, an alternative approach is to “try to bring the movement into the classroom.”

To that end, he co-edited a book of social studies lessons on climate change, A People’s Curriculum for the Earth. It was published by the Milwaukee, Wisconsin–based nonprofit Rethinking Schools.

The book contains stories, poems, articles, graphics, role plays and simulations to help teachers address climate justice: not only the scientific evidence for human-driven climate change but the social dimensions, too. In a simulation called the Thingamabob Game, students play the role of CEOs at major manufacturing corporations, working to maximize their profit — all while producing new “thingamabobs” drives carbon dioxide levels up.

How does climate change affect individuals from around the world differently? Highly effective and engaging role playing/scavenger hunt style activity from @ZinnEdProject and @RethinkSchools. pic.twitter.com/tRv2aXoNF5

— Brett Benson (@MrBensonNMS) May 13, 2019

Another lesson in the book is the Climate Change Mixer. Students act as people around the world, learning how climate change affects different groups including farmers, activists, political figures, oil executives and indigenous people.

“[I]t was highly effective because our primary learning goal was for students to be able to understand the consequences of climate change, and this activity enabled them to gain a basic understanding of how people throughout the world are impacted by climate change,” Brett Benson, a history teacher in Omaha, Nebraska, wrote in an email to Ensia. Benson used the activity with some 160 high-school students as “hook” for an assignment over the following days in which students analyzed and wrote short essays on documents related to the consequences of climate change.

In April, the Zinn Education Project — a partnership between Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, another education nonprofit — launched a Teach Climate Justice website. It offers teachers free resources on bringing climate change into social studies classrooms, including some of the lessons from A People’s Curriculum for the Earth.

While those lessons are geared toward high-school students, Natalie Stapert wondered if she could bring some of them to her middle schoolers. That thought spawned an effort to redesign the sixth-grade humanities curriculum at the Lowell School, a private school in Washington, D.C., where Stapert is a teacher and language arts and social studies coordinator.

Lowell’s new sixth-grade humanities curriculum incorporates activities like the Thingamabob Game and the Climate Change Mixer — slowed down to work for younger students, with more time for background knowledge and vocabulary — and is centered around reading novels, such as Exodus and A Long Walk to Water, that touch on climate and environmental themes. Students also conduct hands-on experiments, developed by the California-based Mobile Climate Science Labs, to learn about the greenhouse effect. And they take an overnight field trip to the Chesapeake Bay’s Tangier Island, which is threatened by rising sea levels.

“We did not approach it from a climate activism standpoint,” says Stapert. While many of the school’s teachers and students have begun taking action since learning more about the issue, the initial impetus was student learning. The old sixth-grade curriculum, a traditional social studies class focused on world cultures and geography, wasn’t engaging all of the kids.

“We looked for opportunities for the learning to be more meaningful so that they would have more internal motivation to work hard and enhance their skills,” Stapert says.

In developing the curriculum, school leaders consulted with NOAA; CLEAN; Climate Generation, a Minnesota-based nonprofit that focuses on climate change solutions; and other organizations.

A new paper in the journal Environmental Education Research, to which Stapert contributed, suggests that sixth graders have higher reading scores and climate literacy after they go through the curriculum. Stapert cautions that it’s difficult to draw direct causal links, and the paper itself notes that the small sample size renders the effect statistically insignificant — but it provide a foundation for future study.

The curriculum also includes discussion of new ideas and information about climate solutions from businesses and scientists, as well as a field trip to talk to lawmakers. Stapert says that these efforts stop the topic from becoming too overwhelming by helping students “understand that when they act, things get better.”

Make the World a Rainbow

Even the youngest students can take action. Christie-Blick recounts the origin of her website, Kids Against Climate Change, recalling a hot day in June near the end of one school year. After learning about climate change, her fifth-grade students weren’t content to skip to summer break.

Student artwork on the website Kids Against Climate Change varies from somber to hopeful. Image courtesy of Kids Against Climate Change

“The kids said, ‘We need to get this out on the internet,’” Christie-Blick says. She agreed, and the students went to work, drawing pictures and making videos. Several years later, the site offers a list of resources for teachers, hosts student artwork and serves as a climate change discussion forum for students.

With funding from NOAA, the site is free to use, and Christie-Blick moderates all of the comments. Each page ends with hundreds of comments from kids, identified by first name and country. “I think we should stop polluting so we can slow down climate change,” writes Ferenc.

“One way that kids can help to stop climate change is to use bikes instead of cars,” writes Laila. “Cars let out a lot of carbon dioxide.”

The site is where Maya’s drawing of the greenhouse effect, complete with a sad sun and frowning Earth, is featured. But it’s also home to symbols of hope. As students learn about not just the causes and impacts of climate change, but also the actions they can take — individually or politically — to make a difference, they can find optimism. In one colorful piece of art, for example, an elementary student from the U.S. named Sofia shares her simple call to action: “If we work together we can slow down climate change and make the world a rainbow.”

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

Dumsani