November 12, 2020 —  Arshak Makichyan, a 26-year old violin student, had been following Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg’s story closely. In March 2019 he decided he couldn’t stay silent anymore — he had to go on a climate strike in his own country: Russia. For several weeks he stood alone. Later other activists joined in; together they started Fridays for Future (FFF) in Russia.

Arshak Makichyan, a 26-year old violin student, had been following Swedish environmental activist Greta Thunberg’s story closely. In March 2019 he decided he couldn’t stay silent anymore — he had to go on a climate strike in his own country: Russia. For several weeks he stood alone. Later other activists joined in; together they started Fridays for Future (FFF) in Russia.

Across the world, global climate strikes, inspired by Thunberg and FFF, brought millions to the streets in September of that year. But in Russia it was a different story. Russian megacities of Moscow and St. Petersburg have well over 15 million residents between them, yet FFF protests in those cities had at most 200 participants.

There are myriad reasons for this; young activists in the country say they face difficulties trying to apply pressure from within — from a lack of grassroots protest culture to obstacles from the government. Organizing demonstrations and convincing people to care about climate change in Russia is difficult, Makichyan says, as activists face pressure on many fronts, from both the public and the government.

Outside Pressure

Russia is warming 2.5 times faster than the planet as a whole. For two years in a row, fires across the Arctic, including in Siberian forests, have caused record CO2 emissions. An international team of scientists established that climate change made extreme heat waves in Siberia 600 times more likely, causing such destructive fires. Government efforts to suppress the fires are widely covered by Russian media, yet climate change is rarely mentioned as their cause or a contributing factor to their intensity.

For two years in a row, fires across the Arctic, including in Siberian forests, have caused record CO2 emissions. © Julia Petrenko / Greenpeace

At the same time there is a growing concern among business elites on how rapid decarbonization of Europe could affect the fossil-fuel industry, which is a huge part of Russia’s economy — around 40% to 50% of the country’s federal budget comes from taxes on oil and gas industries. Just this fall Greenpeace, together with other activists and researchers from leading Russian universities, came up with a Russian version of the Green New Deal.

“Russian climate policies are likely to be reactive rather than proactive,” Tatiana Lanshina, an economist and sustainable development researcher at RANEPA (Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration) and one of the Green Deal for Russia authors, wrote in an email. “Signals [to implement reforms] are coming mostly from outside, and they are related to the EU green deal and other international processes.”

Fighting for Survival

The Covid-19 pandemic proved to be a serious blow to FFF around the world. But after organizers initially moved their protests online in the spring, the movement began to recover — first lone protesters appeared on the streets, then small groups and later crowds. Yet in Russia, the story is different. The FFF movement still fights for its survival, with several challenges at once related to education, organizing and legality.

While Thunberg first decided to strike for climate after learning about the severity of the problem in school, Makichyan had to learn about climate change by himself. In Russia the topic is seldom taught in schools and universities, Makichyan and others say. Despite his university education and ability to speak English, it still took Makichyan six months to make sense of climate science on his own.

In Russia, it’s common to hear people joke about starting to “grow bananas in Moscow,” says Makichyan. “Warming” is viewed positively — something that will finally make cold regions of Russia livable and arable. As a result, while most Russians agree that climate change is happening, they consider problems such as dirty lakes, waste management and air pollution more relevant to their lives.

Some organizations are trying to inform and educate Russians about the true cost of “bananas in Moscow.” The ECA-movement, a Russian non-governmental organization (NGO) focused on promoting environmentalism, runs two educational partnerships with the Russian Ministry of Education — Green Universities of Russia and Green Schools of Russia. ECA volunteers discuss environmental issues in state-run schools and help teachers organize lessons for students. Green Schools of Russia has educated 2 million students across the country, says Anna Kudasheva, a coordinator at Ecowiki — a platform started by ECA to promote environmental values online.

Anna Kudasheva, a coordinator at Ecowiki, holds a sign that says, “Climate is changing. What will be here tomorrow? Will we be here?” Photo courtesy of Fridays For Future Russia

Alexei Goncharov, who has led FFF efforts in St. Petersburg, participated in Green Universities of Russia as a student organizer. He’s skeptical about the project’s ability to help climate reforms because he says he believes it’s simply an attempt by the government to keep up an appearance of real change, while in reality “it has no power” to bring about environmental progress. Although he does give the project credit for helping participants begin to learn about climate change, he thinks real opportunities for change are in decentralized grassroots campaigns separate from the government.

But decentralized grassroots movements aren’t necessarily easy to organize in Russia. Makichyan says there is a lack of basic protest culture in the country.

“People don’t understand how a grassroots movement works,” he says. “They may be waiting to be told what to do, to see some detailed plans — they don’t get that it’s up to them. This problem may be as complex as the climate crisis itself. And we are just starting to sort out these problems.”

Although meetings, rallies, demonstrations, marches and picketing are legal, they need approval by local administrations, and according to the Russian NGO OVD-Info, such requests are regularly rejected. At times, according to OVD-Info and Mackichyan, authorities have offered to allow protests away from city centers, where, says Makichyan, it makes no sense to protest because such efforts would lack the attention that makes the protests effective. So, often activists rely on protesting alone — officially called a “solitary picket” — for which no permit is needed.

Meanwhile, while people under 18 can legally participate in pickets, only people over 18 can organize them, which has led to an open question about whether people protesting alone are “participants” or “organizers.”

“Police sometimes detain underage activists, call their parents and try to scare them,” Makichyan says. The result is most school-age students are kept out of FFF strikes.

Fear of arrest in general is a major reason so few people participate in the movement, says Makichyan, who has been detained many times, once ending up in jail. “[They arrested] me for an unpermitted rally for three people,” he says. He claims he applied for a permit 10 times and officials kept denying his requests. After the 10th denial, “then we came out anyway,” he says.

FFF activists around the world rallied to his defense, picketing in front of the Russian embassy in Portugal and other locations. After six days Makichyan was released.

“I have lots of respect for everyone who’s taking on the burden of striking for the climate in Russia,” says Annika Kruse, a German FFF activist who knows Makichyan personally. “In Germany we would never get arrested for striking.”

Burnout and Inspiration

Makichyan says that the uphill battle activists face in Russia takes a toll. “It is very hard to bear it all and very hard not to burn out,” he says. “Many activists just burn out when they see all that mess.”

While protesting alone or with a handful of supporters, Elizaveta Gromyko, an FFF participant in Vladivostok, says she often faces verbal harassment and taunts from passersby.

“A few times I left the climate strike with tears in my eyes,” she says. “But in these moments, I try to tell myself: ‘No one has a right to cast doubt onto things that you stand for.’”

Despite this, Gromyko has had positive experiences protesting, too. “During the October 2019 global strike, a group of 10- to 12-year-old girls approached us. With great interest they started to ask questions,” she says. “I was very much surprised when, after a long conversation, they asked us if we have spare carton-boards, so they could sketch some drawings of their own and take part in our climate strike.”

“There are successful stories, and they are inspiring,” says Kudasheva. This past summer, Kudasheva says, Ecowiki started an online-activism campaign asking people to adopt environmentally friendly practices or take part in FFF protests. And Svitlana Romanko, 350.org managing director for Eastern Europe, points out that other groups besides FFF are raising climate awareness around Russia, such as Friends of the Baltic, Environmental Movement 42, and Chelyabinsk Breathe! At the same time, Romanko says these organizations are often understaffed. “For such a big country as Russia these organizations need to have a lot of volunteers and resources for better coverage,” she says.

https://twitter.com/sofyepifantseva/status/1309577304738328578?s=20

Another way to organize around climate issues, says Goncharov, is to focus on local issues in provincial towns and Indigenous communities. Indigenous people in Russia already have observed how climate change is impacting their communities, and Goncharov sees them as natural participants to move the climate conversation forward in Russia. In December 2018, 30,000 came out to protest against the Shiyes waste disposal facility in the Arkhangelsk region, and in August 2020 thousands of Bashkyr people and other local residents defended the Shihan Kushtau mountain from mining development. Both projects were eventually shut down. And while neither protest was focused on climate change, they were grassroots efforts — addressing one of Makichyan’s concerns about limited grassroots protests in Russia.

Dancing for Climate

On September 25, 2020, Fridays For Future groups around the world held their first physical mass protest since the Covid-19 pandemic began. In Hamburg, Kruse expected 10,000 people to participate; organizers estimate that the count was closer to 16,000 protesters, and 200,000 gathered on streets throughout Germany.

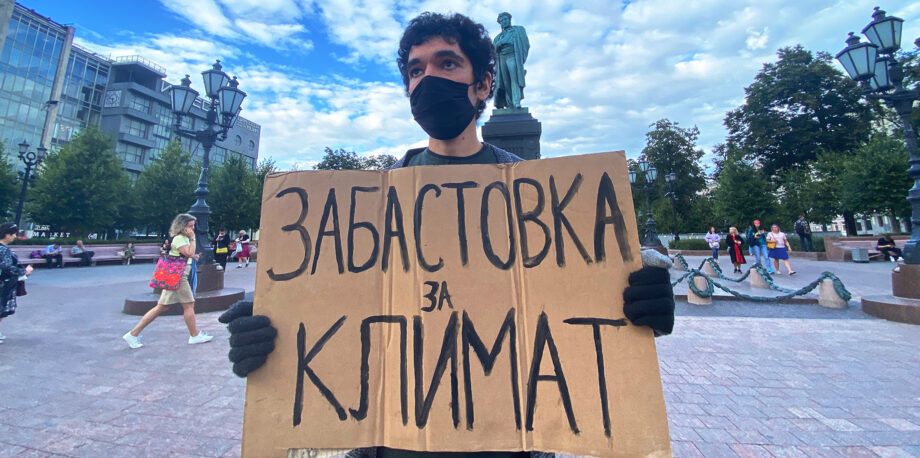

Makichyan prepared for the possibility that he would be the only protester in Russia — just as it was when he marched for climate the first time, a year and a half ago. Yet this time, the movement exceeded his expectations. Along with solitary pickets in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kaliningrad and Murmansk, more than 100 people protested with their banners online. Not only that, but FFF and Greenpeace found a new way to go around government restrictions and organized street dance shows instead of the usual picketing.

“We’re not allowed to strike for climate, so we’re dancing for it,” tweeted Sonya Epifantseva, an FFF organizer. Around 90 people performed from locations in Moscow, St. Petersburg and other cities.

At the same time the Russian government is facing more pressure to implement climate reforms, natural disasters such as Siberian fires or floods in the east of the country have raised more concern among the general population, moving more people to act on environmental issues.

Climate activism around the world raised awareness long before governments made any serious reforms, and activists have pressured governments to enact laws and environmental regulations, says Lanshina. “The same we will see in Russia. Unfortunately,” she says, “this process can take some time.”

Editor’s note: Nikita Ponomarenko wrote this story as participants in the Ensia Mentor Program. The mentor for the project was Fred Pearce.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

And it's not "around 40% to 50%" of oil&gas profits in Russian budget. It's 28% in 2020 and 36.5% in 2019.