May 23, 2024 — A proposed state constitutional amendment introduced in the Michigan House in April would put the right to clean air, water, soil and a stable climate on par with other fundamental liberties like the freedoms of speech and religion.

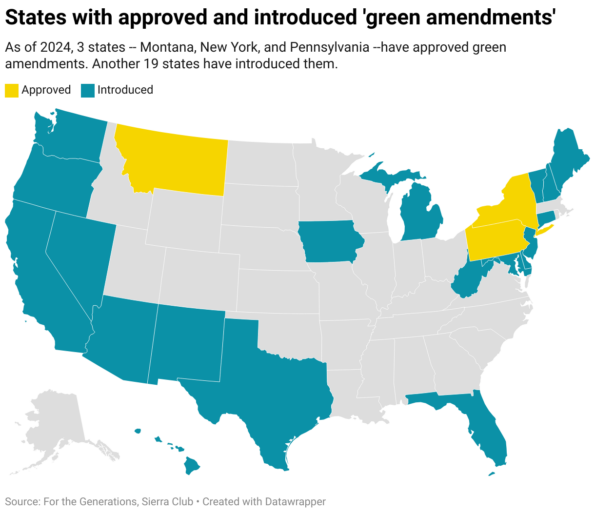

The Michigan Green Amendment, introduced by Rep. Rachel Hood (D-Grand Rapids), follows the passage of amendments in Pennsylvania, Montana and New York that have been used to fight environmental threats like PFAS contamination and hydraulic fracking in residential neighborhoods. More than a dozen other states are also considering such amendments.

“The goal is to make sure that our government is making better decisions so that our fundamental rights are protected,” says Maya K. van Rossum, founder of the nonprofit Green Amendments For the Generations. The amendment could offer legal recourse for residents whose right to a healthy environment is infringed upon and protect state laws from federal environmental rollbacks.

Pennsylvania’s green amendment has helped environmental advocates secure important victories in recent years. Although the state’s Environmental Rights Amendment was enacted in 1971, it didn’t have much impact until 2013, when the Pennsylvania Supreme Court cited the amendment in its decision to overturn a requirement that municipalities allow oil and gas developments in all zoning areas.

In 2018, former Democratic Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf referred to the amendment in an executive order creating the state’s PFAS action team, which was followed by the state setting limits on two common types of PFAS in drinking water.

A State Strategy for Green Amendments

Pursuing green amendments at the state level could be far easier to pass than a federal constitutional amendment and win substantial protections for residents, van Rossum says.

“When it comes to environmental protection, states have a tremendous amount of authority,” she says. Indeed, on issues like regulating PFAS chemicals and addressing vehicle emissions, states often lead the way in adopting stricter environmental protections.

Green amendment advocates argue that the approach establishes a framework integrated into state policymaking, protecting residents from environmental threats and preventing problems before they arise, as opposed to passing laws against individual environmental threats.

Washington state Rep. Debra Lekanoff (D) previously said an amendment would ensure that “every environmental policy that you build [in] Washington state, every regulation, everything you build across the state, every fiscal note you invest in Washington state is adequately providing the healthy environment.”

However, some have argued that green amendments could lead to litigation that blocks essential projects. The New Mexico Legislature’s Legislative Finance Committee said in a 2023 report that a green amendment could potentially be used as a “roadblock to pursuing clean energy projects as part of New Mexico’s renewable energy transition,” and that, “the legal uncertainty the amendment could create might result in costly litigation that could impact the financial feasibility of certain energy projects.”

In response, van Rossum said New Mexico’s proposed amendment could actually help clean energy projects defend against legal challenges because of the clause requiring the state to safeguard a stable climate.

She has also argued that green amendments could protect states from rollbacks in federal regulations. The prospect of a second Trump presidency could give this argument more urgency as the Heritage Foundation and other conservative organizations advocate for shrinking the Environmental Protection Agency and directing its focus away from the climate crisis.

States frequently pass constitutional amendments. The last amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed in 1992, whereas Michigan passed three in 2022 alone.

In Michigan, a constitutional amendment can be passed either by a two-thirds vote of both chambers of the legislature, at a constitutional convention or with a ballot initiative.

Passing such a measure with a ballot initiative may be more likely given the closely divided legislature.

But van Rossum says that, for now, the important thing was to educate lawmakers and voters about what such an amendment would mean, which could also lead to a push for a federal amendment.

“Going state by state by state gets us critical protections in the near term and also allows us to undertake the education and the organizing needed to ultimately succeed at the federal level,” she says.

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on Planet Detroit and is republished here under a Creative Commons license. Ensia and Planet Detroit previously collaborated on a reporting project, “Inundated: Flooding and vulnerable communities in the Great Lakes region,” along with the Institute for Nonprofit News, Borderless, Sahan Journal, Wisconsin Watch, the Guardian and Inside Climate News, which looked at flooding vulnerability for cities, rural areas and Indigenous communities throughout the Great Lakes region from sources that range from excessive rain and overflowing rivers to lake storm surges and sewage system flooding.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!