April 8, 2014 — In opening our eyes to the unseen wonders of the ocean Jacques Cousteau is thought to have said, “People protect what they love.” A variation, perhaps, on the words of the Senegalese poet and naturalist Baba Dioum: “In the end, we will conserve only what we love. We will love only what we understand. We will understand only what we are taught.”

On a planet where 71 percent of the surface is covered by water, the ocean is critical for life. It feeds us, regulates our weather patterns, provides over half of the oxygen we breathe, and offers energy and economic benefits. An estimated 350 million jobs globally are linked to the ocean. One billion people living in developing countries depend on fish as their primary source of protein. Coastal habitats store five times more carbon than do inland tropical forests. In recent weeks we’ve seen the critical role of the ocean in the latest warnings from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the launch of the White House Climate Data Initiative and the ongoing search for missing Malaysia Airlines flight MH 370.

But all is not well. The ocean holds five times more pollution than it did in 1960, due largely to inland agricultural runoff to the coast, and less than 2 percent of the ocean is legally protected in parks and reserves, as compared to 12 percent of global land areas. Only 5 to 10 percent of the waters beneath the surface and the ocean floor have been explored and mapped in a level of detail similar to what already exists for Mars, Venus and the dark side of the moon. And there is a general lack of understanding that what we do to terra firma — including our streams, lakes and groundwater — ultimately affects the ocean and therefore matters greatly.

The term whole Earth may bring to mind data and images sent back from satellites in space, but there is much more to it than that.

How do we raise such awareness — not to mention create a call to action? One key way is by embracing the power of whole Earth observation and the data it provides.

The term whole Earth may bring to mind data and images sent back from satellites in space, but there is much more to it than that. Whole Earth observation now takes place at a wide range of scales here on Earth as well.

For example, data collected within the ocean from mapping systems located beneath a ship are linked to underwater video or photographs collected from vehicles towed behind a ship and collated to samples and measurements collected from an instrument or vehicle launched away from the ship or operating independently on the seafloor. These data include measurements of the temperature and salinity of the ocean that help us track El Niño events; of the ocean’s depths for charting, navigation, finding lost objects, and pinpointing regions of sea level rise and coastal flooding; of the abundance, diversity and overall health of hundreds of species of ocean life (including those in commercial fisheries); of the speed and direction of currents, storm systems and dangerous tsunami waves from underwater earthquake sites; and much more.

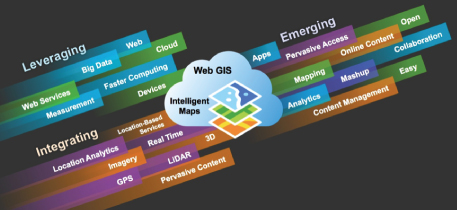

Such observations can produce maps that are becoming increasingly intelligent. By linking geographic coordinates with extensive databases and sophisticated spatial analysis algorithms in geographic information systems, they do more than feature pushpins, pop-ups or static lines. These maps can tell time, process events through both space and time via statistics and numerical models, send alerts to a computer or mobile device if something enters an area of interest, or help design marine protected areas. They are changing what we measure, how we analyze, what predictions we make, how we plan, how we design, how we evaluate and ultimately how we manage it all. And increasingly this is all taking place in the cloud and becoming more open, without the need for cumbersome desktop hardware and software with their steep, long learning curves.

Intelligent mapping as realized through GIS on the web is changing how we connect to and understand a changing world. It leverages and integrates several technologies and trends, with several areas that are quickly emerging. Image courtesy of Esri.

But it’s not just smart maps that can spread the word about the importance of oceans. Pairing these maps with storytelling, something we’ve relied on for communication for millennia, to create “story maps” is important for delivering the messages all those underlying data are telling us. The visual stories we create with maps help scientists communicate among themselves and with policymakers who have the power to make decisions that affect the entire Earth. Importantly, none of this requires advanced training in cartography or GIS, though it is all done with sophisticated cartographic functionality behind the scenes.

GIS is helping us reach a deeper understanding of our oceans. This story map explores the impact of climate change on gray whale feeding grounds, tracked using GIS. Photo courtesy of Esri.

If it is true that we will love and protect only what we understand, we need to start using the technologies we have more effectively to help us understand our world. In our lifetime we’ve seen one mapping technology completely transform us as human beings: the Global Positioning System made it so that we’re rarely lost. If GIS became as ubiquitous, the resulting data collected from whole Earth observation, if communicated correctly through things such as story maps, would allow our organizations, communities and societies to better understand what actions need to be taken to improve or save our environment.

Noted oceanographer and citizen of the planet Sylvia Earle has said, “now we know that our lives depend on the ocean.” It’s time to start using the technology we have to protect it.

![]()

To explore the world of intelligent maps even more, check out Story Maps and Intelligent Web Maps.

Editor’s note: The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily of Ensia. We present them to further discussion around important topics. We encourage you to respond with a comment below, following our commenting guidelines, which can be found here. In addition, you might consider submitting a Voices piece of your own. See Ensia’s “Contact” page for submission guidelines.

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!