May 15, 2013 — It never fails. Whenever we talk about meeting the world’s growing demands for food, energy and water, chances are good that we start with ways to produce more of these vital resources. We talk about solar panels, nuclear power stations, GMOs, advanced hydroponics facilities, desalination methods, and other, latest whizbang technologies.

We seem obsessed with the need to always deliver more energy, more food and more water, without asking the obvious question: Can we use our existing resources better by becoming more efficient and reducing the huge amount of waste we see today?

Let’s look at food as an example.

There is no doubt that the demand for food is increasing. Population growth alone — from over 7 billion today to an expected 9 billion by 2050 (a 28 percent increase) — would, if all else stays the same, imply that 28 percent more food is needed. But all else is not staying the same: Diets are changing, with dramatic increases in meat and dairy consumption as much of the world becomes wealthier. All told, the expected changes in population, wealth and diets — assuming that recent historical trends are a good guide — would result in the need to roughly double global crop production by 2050, according to University of Minnesota ecologist David Tilman and colleagues. And increases in biofuel consumption may further exacerbate the situation.

Many in the agricultural sector use this estimate to justify a massive investment in agronomic practices and improved crops, including genetically modified organisms. The argument goes like this: We need to double the world’s food supply. To do so without clearing the world’s remaining forests, we’ll need to double the average yields on the world’s existing farmland, and that will take more advanced agricultural technology.

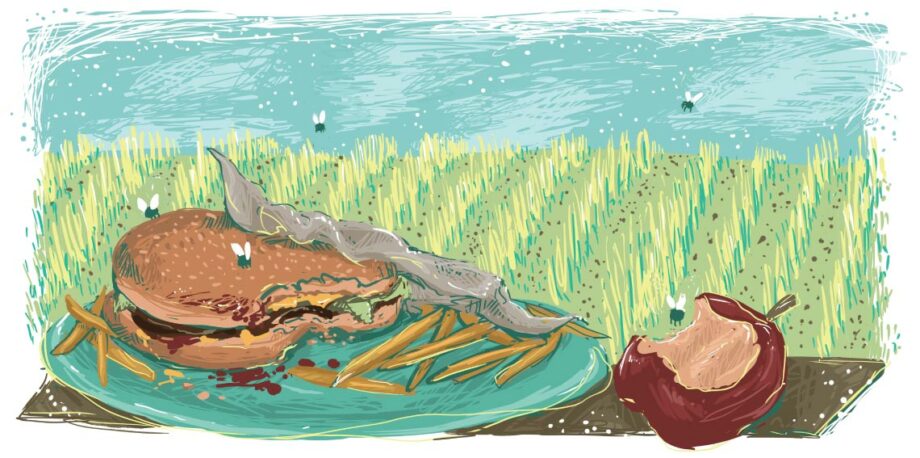

It’s estimated that, on average, 30 to 50 percent of the world’s food is never consumed. It’s wasted somewhere in the supply chain that connects farmers to consumers.

Yes. And no. As I’ve written about extensively, this is not the whole story.

It turns out that recent investments in agricultural technology and advanced genetics have been making only a modest dent in meeting our global food demands. In the last 20 years, the world’s total agricultural production increased by roughly 28 percent. Only 20 of those 28 percentage points are attributable to increased yields — roughly 1 percent per year, since crop yields tend to grow linearly. And for the last decade, my colleague Deepak Ray has shown that crop yields for many important crops have, in fact, begun to slow down and stagnate in many regions.

Even if crop yields were not stagnating, the challenges of meeting future food demands from yield increases alone is daunting. Doubling global crop production by 2050 would require a 2.7 percent annual (noncompounding) yield increase. Clearly, with yields increasing at roughly 1 percent per year, we are far from meeting that goal, and that’s with decades of research and investment in new agricultural and genetic technologies. Simply put, until something new comes along, genetics and agronomics alone are unlikely to get us to the solution we need.

That’s where waste comes in.

It’s estimated that, on average, 30 to 50 percent of the world’s food is never consumed. It’s wasted somewhere in the supply chain that connects farmers to consumers. In poorer countries, much of the waste happens between the farm and the marketplace, because crops are lost to pests or due to a lack of infrastructure (trains, trucks, roads, warehouses, etc.) to get products to market. In rich countries, most of the food waste happens around the retailer or consumer — in our supermarkets, restaurants, cafeterias and refrigerators. And while it is bad enough that we lose the food in rich countries, in poor countries the food is lost, but so is the farmer’s income — a double tragedy.

So if we’re losing 30 to 50 percent of the world’s food through waste, and all of the agricultural technologies of the past 20 years have only given us a 20 percent increase in crop yields, why aren’t we focusing at least as much attention on reducing food waste? Even cutting waste in half would be a huge step toward global food security and a boon for the environment. Billions of dollars are currently invested in genetic modification, advanced agricultural chemicals and farm machinery. Where is the comparable investment in reducing food waste?

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

- modern farm machinery that minimizes losses during harvest

- resistant crop varieties and insecticides to combat storage pests and reduce spoilage

- improved storage, packaging and cooling technologies

- communication technologies to achieve more timely matching of supply and demand in markets

- frozen and canned food to extend shelf life

- sensor technologies to detect spoilage in perishable foods

I'm not so sure that tackling food waste (in rich countries) is a low-hanging fruit, holding technology constant. Consumers could easily reduce their food waste if they went shopping every day. Retailers could avoid throwing away food if they restocked more frequently and collected enough information about consumer demand. But obviously there are non-trivial costs associated with such strategies. I would argue that focusing on (post-)harvest losses in developing countries would be a better starting point, especially if the goal is to improve food security.

Ulrich Koester has some more useful comments: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0306919213000341

But I am not saying that technology is not useful for addressing food waste. In fact, I think it would be excellent to see more R&D and innovation in this space.

Thanks for your useful and constructive comments.

it's encouraging to see discussion of food systems assessed similar to energy systems. clearly they are strongly interrelated and follow a similar analysis as soft vs. hard path, i.e., decentralized, redundant, highly localized models. while food systems cannot be practically analyzed separately from the current globalized economics of food, this focus on food efficiency and end use matching may soon prove a much bigger bite for the buck, to twist the phrase...

Far healthier for people and the planet is to simply not eat the meat in the first place. Huge reductions in meat consumption are required to meet James Hansen's climate change imperative of rolling back 200 years of deforestation.

But talking about that in a serious sustained way risks more than "coming out" as gay. Marion Nestle blew the whistle on this in "Food Politics" but has anything changed? Not as far as I can see.

We still have serious science journals like "Science" publishing unscientific anecdotal apologetic rubbish about meat and nobody blinks. It's 2010 "Food Security" issue was classic for its allowance of absolute drivel getting past peer review and ending up as citable "fact". I can send an analysis if ensia is interested.