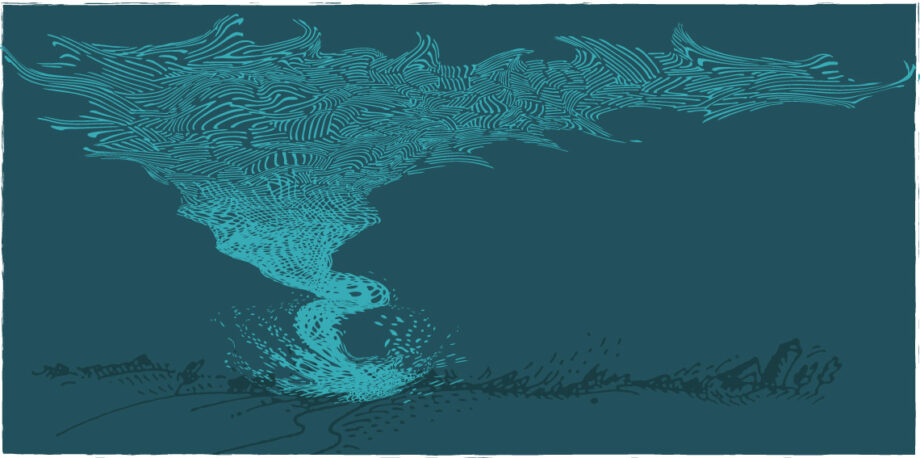

July 12, 2013 — Moore, Okla., has plenty of exposure to big tornadoes. On May 20, 2013, a mile-wide twister ripped through the town, following a similar track to that of an infamous tornado that devastated Moore back in 1999. Just 11 days later, on May 31, the widest tornado ever measured in the U.S. gouged a path less than 40 miles away.

What Moore doesn’t have plenty of is basements. In the wake of this year’s storms, a local homebuilder told CNN that 15 percent or fewer of residents had any kind of underground shelter. Though central Oklahoma is one of the most tornado-prone places on Earth, basements are a rarity across the entire region. This discrepancy can’t be explained by technical issues such as soil quality or groundwater. According to geologists and engineers, it’s primarily a cultural phenomenon. Experts know why basements can save lives in a tornado, and they know how to build them. But all that information is next to useless if nobody wants a basement to begin with.

Culture has a big impact on disasters — how we prepare for them, how we respond to them and even how we could prevent them. In fact, some social scientists who study disasters say they are the result of culture — what happens when natural forces or human error come crashing into existing social systems. “Nothing is a disaster until it intersects with a specific society that has vulnerabilities that are the result of decisions made over decades … often, decisions that were made without really thinking,” says Joseph Trainor, assistant professor at the University of Delaware’s Disaster Research Center.

In Oklahoma, the tornadoes intersected with decades-old expectations about what a nice house looks like and how valuable different features are when it comes time to sell.

Most people will never experience a twister careening through their living room. It’s what Trainor calls a “low-probability, high-consequence event.” When faced with such events, we tend to focus on the low-probability part.

Most houses in the state are built as slab-on-grade — builders pour a concrete pad and construct the building on top of that. It’s a cheap way to build, much cheaper than digging down eight or 10 feet and making a basement, says Gerald Miller, a member of the Geotechnical Engineering Program faculty at the University of Oklahoma. Oklahomans have built homes this way for years, so people aren’t used to seeing basements, and builders aren’t used to making them. And residents have heard stories from older generations about how damp and leaky basements can be. Even though the technology exists to build comfortable, clean basements today, Miller says, nobody prioritizes them. Oklahomans think of basements as expensive liabilities before they think of them as potentially lifesaving shelters.

And that matches up with how humans think about risk in general. Even in “Tornado Alley” most people will never experience a twister careening through their living room. It’s what Trainor calls a “low-probability, high-consequence event.” When faced with such events, we tend to focus on the low-probability part. In the case of Oklahomans and their nonexistent basements, that means most people would choose to spend a few thousand dollars on granite countertops that will definitely improve the value of their home, rather than invest the money in a basement that could save them from a tornado that may or may not ever come. The local culture determines how the disaster plays out.

Of course, this means if you want to reduce the impact of a disaster, or stop one from happening altogether, you have to change the culture — and that can be a lot harder than implementing a technological fix.

Top-down strategies are one way to do it. Oklahoma could pass a law, for instance, mandating basements as a part of any new construction. But that kind of solution can be unpopular, especially if the public isn’t exactly clamoring for the change. Instead, Trainor says, it’s important to look at the problem as part of a larger system. Oklahoma’s lack of basements is just one aspect of a bigger question: How can we reduce the number of people who die in tornadoes?

The death toll is the real problem here, and there are lots of ways you could solve it. You could improve consumer education and make sure people understand how basements have changed over the past half century. You could change the way home builders are trained so more of them have experience building basements, which would lower the cost of construction. You could pass laws that encourage communities and neighborhoods to voluntarily build shared shelters. And you could bypass the basement issue entirely by improving tornado warning systems. Right now, Trainor says, people get, at best, a 15-minute warning of a tornado threat — and 75 percent of those end up being false alarms. If those numbers could be improved, maybe there would be fewer people in harm’s way, because they’d have more confidence in the forecast and more time to figure out how to protect themselves.

There’s not an absolute solution in that list of possibilities, and that’s kind of the point. Systems — including the cultural systems that affect how many people die in tornadoes — are complex. There are lots of different factors at work, and the real solution lies in addressing and tweaking all of them, not in bemoaning the fact that people aren’t doing something right. If we want more resilient communities, we have to start by thinking about communities as social systems and let the old idea — that individuals will make simple, rational choices based solely on what science says is good for them — blow away in the wind. ![]()

Editor’s note: The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily of Ensia. We present them to further discussion around important topics. We encourage you to respond with a comment below, following our commenting guidelines, which can be found here. In addition, you might consider submitting a Voices piece of your own. See Ensia’s “Contact” page for submission guidelines.

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

and maybe the high ground water levels have something to do with it too....

as for "warnings": in rural areas, you go outside and check for funnels. The radio reports are useless when the radio station tells you there is a funnel ten minutes after it hit your garage.

I don't think these are really cultural decisions, I think they're more economic ones. And I wouldn't dismiss technical issues so quickly. The soil here, particularly in Western Oklahoma including Moore, has high clay content, which makes building basements a risky decision for builders and developers - and a risk for homeowners, too. Slab foundations are notoriously prone to cracking and shifting with changing conditions. A basement in these conditions, even with improved techniques, is a risk most builders don't want to take. If you're a builder - which would you rather do, build 100 slab houses in which the settling might not even be noticed for years, or 100 slab homes in which 5-10-20 percent have leaks or need repair the first year?

Builders have avoided the financial risk, and have convinced homeowners that a basement is risky to own.

It wasn't mentioned in the article, but companies that build above-ground "safe"rooms are in high demand right now.

Thanks for the little bit of reverse culture shock, it was invigorating.

-jeff

Here in Germany I hear about those tornado incidents regularly and I always think; "Why do they live in lightweight constructions in 'that area' and don´t even have at least some kind of shelter...", like a solid concrete or brick basement, which also serves as a storage, sometimes additional living space, with enough space for a small workshop or hobby room in most cases.

And I think: "This would never, ever happen to our solid (brick-)home from the 1920s we live in for rent". And, yes, we have a basement like about 90 % of all homes in Germany.

If a Tornado would hit our home, maybe the roof would be kind of "off", but it would never happen that our house would be completely gone with the wind.

And tornados are pretty rare here, like almost negative probability.

But I think most of the buildings here are more tornado-proof than those in the tornado-alley in the US(!). So that makes me (and probably others) think: "Why?!".

But we also have a similar problem, which is, that people like to settle in areas which are likely to be flooded once in several years.

In Germany we had a "century-flood" in 2002 which caused billion € damages. This year almost the same happened to the same areas. Again billions of € damage.

Only VERY few improvements were made after that disaster 11 years ago.

People as well as the administration won´t learn anything. "This probably won´t happen again in the actual/next legislative period". And the actual elected polititians have the opportunity to present themself "as a helper in time of need".

Nice anecdote btw; the driver of my universities president is a civil engineer and specialized in flood-protection techniques. "It´s hard to find a job," he said, "projects are all 'too' long term and too expensive and after a while people forget about the flood which ruined their homes". "After they have cleaned the mess up and life becomes normal again, they don´t think about prevention anymore..."

And that´s the point, "people tend to forget" and tend to blind out the risks. Until it strikes them (again [and again]).

And then they beg for assistance because they were struck oh-so hard and "out-of-nowhere" (in their beliefs...).

But prevention?!

Think there should be guidelines by the government, if people tend to stick to the "it hopefully won´t hit me"-pattern.

BTW: I like the term of a "low-probability, high-consequence event". Insurance-speech.

If you don´t build a shelter and get killed by a tornado, they don´t need to pay maybe except for the burial of you and your loved ones.

Probably cheaper than insuring your house WITH a basement and shelter.

I lived in the south for a while, in a tornado prone area, and I thought that not having a basement was insane. People out there just view tornadoes as another part of life; something they've lived with all their lives, so tornadoes are no big deal. When a tornado warning comes, everyone heads to the bathroom or a closet!

The converse of this is risking a slight social perception that your laminate counters are shabby against your ability to protect yourself and your family from a natural disaster.

Rebuilding every house in the state, or even increasing the cost of new ones, works out at a huge cost per life saved. Better healthcare or road improvements would give way better value.

Mary Bagorio

marybagorio143@gmail.com