March 1, 2022 —  Decades ago, the Welsh academic Raymond Williams wrote, “Nature is perhaps the most complex word in the language.” So perhaps it’s not surprising that organizations and individuals working at the interface of climate change and biodiversity conservation have wildly different opinions about what are commonly termed Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) and Natural Climate Solutions (NCS) to the climate crisis.

Decades ago, the Welsh academic Raymond Williams wrote, “Nature is perhaps the most complex word in the language.” So perhaps it’s not surprising that organizations and individuals working at the interface of climate change and biodiversity conservation have wildly different opinions about what are commonly termed Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) and Natural Climate Solutions (NCS) to the climate crisis.

The idea behind these solutions is that protecting and accelerating natural processes can help solve the climate crisis by removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, storing carbon in biomass, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions from biomass to the atmosphere. But because nature is all-encompassing — Earth, water, air, fire, living things (including people) — what counts as “nature-based” or “natural” depends largely on who is doing the counting.

But what does and doesn’t count matters a lot in the context of the urgency of the climate crisis and our thus-far inadequate responses to it, as the newly released Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group II report on climate change impacts, adaptation and vulnerability makes abundantly clear. If we don’t succeed in constraining climate change, we will also lose most of the natural world as we know it. Nonetheless, while some proponents of NBS and NCS strive to ensure strong alignment of climate and biodiversity outcomes, others are content to lay claim to nature’s benefits while side-stepping responsibility for the costs to nature that they incur.

In the former camp sit organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which defines NBS as “actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural and modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits.” Similarly, a seminal publication on NCS advanced that definition as “conservation, restoration and/or improved land management actions that increase carbon storage and/or avoid greenhouse gas emissions across global forests, wetlands, grasslands and agricultural lands.”

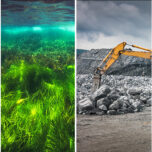

The latter camp includes proponents of bioenergy projects and pro-bioenergy policies. These initiatives often rely on trees as the principal energy source, devastating forests and their wildlife and undermining the role of forests in long-term carbon dioxide removal and storage.

Along with bioenergy, the continuing expansion of monocultural plantations for food and fiber products is at odds with biodiversity conservation, despite the growing interest among some agribusinesses in dressing up a business-as-usual narrative to extol NBS or NCS.

Demonstrably Positive

The cover of ambiguity has allowed this latter camp to gain a foothold — but when that ambiguity is stripped away, it’s clear that it’s nothing but greenwash. To right that, we need to promote and implement solutions that are not just vaguely “nature-based,” but actually and demonstrably “nature-positive” — meaning they help to halt and reverse the loss of natural ecosystems — by 2030, against a 2020 benchmark, while providing climate change mitigation and adaptation benefits.

In the arena of climate change, NBS and NCS now have a firm foothold, with potential for substantial impact — as evidenced by the number and financial significance of announcements made at COP26 in Glasgow last year. While a lot more finance is sorely needed, impact is the only real measure of success and failure. Hence clear questions for nature-positive climate finance seem warranted: How will it help halt and reverse natural ecosystem loss? What are its climate change mitigation and adaptation benefits? And will it help reduce, or exacerbate, existing inequality, including for Indigenous peoples and local communities?

Beyond Ambiguity

As we look to the upcoming Convention on Biological Diversity global conference, it’s time to move beyond ambiguous language that is easily stretched and twisted to mean whatever one wants.

To adequately address the climate emergency, we need to rapidly and drastically reduce greenhouse gas emissions from every sector of the economy — including energy, industry, transportation, buildings and agriculture — and protect natural ecosystems. And we need to especially protect forests and peatlands, the ecosystems that remove the most CO2 from the atmosphere, store the most carbon in biomass and have the most potential for reducing CO2 emissions from biomass to the atmosphere.

To achieve that, we’ll need leaders — from governments and businesses, and especially from within the financial sector, where decisions are made about the allocation of trillions of dollars of investor capital — to embrace, not just nature-based solutions, but nature-positive solutions. That leadership will need to call upon the best parts of our human nature to prioritize and pay for maintaining the chemistry of the thin envelope of atmosphere that sustains us and the rest of the diversity of life on Earth.

Editor’s note: The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily of Ensia. We present them to further discussion around important topics. We encourage you to respond with a comment below, following our commenting guidelines, which can be found on this page. In addition, you might consider submitting a Voices piece of your own. See Ensia’s Contact page for submission guidelines.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!