Editor’s note: This story is the first in a nine-month investigation of drinking water contamination across the U.S. The series is supported by funding from the Park Foundation and Water Foundation.

Once a week, Florencia Ramos makes a special trip to the R–N Market in Lindsay, California. “If you don’t have clean water, you have to go get some,” says Ramos, a farmworker and mother of four who lives in the neighboring Central Valley town of El Rancho.

She has been purchasing jugs of water at the small store for more than a decade now. At first she was concerned that the county well water that flowed through her tap contained high levels of nitrate, a pervasive health hazard across rural U.S., where nitrogen-rich fertilizer and livestock manure seep into groundwater. While it never tasted bad, she recalls her water service provider instructing her not to drink it. Things didn’t get any better in 2016, when El Rancho plugged into the City of Lindsay’s water system. That water was — and still is — polluted with potentially harmful disinfection by-products, which form when chlorine used to kill dangerous organisms in drinking water reacts with manure and other organic matter.

“We’ve always known our water was contaminated,” says Ramos, a member of the AGUA Coalition, a grassroots group that advocates for safe, clean and affordable water, with the help of a translator.

Over the years, she watched as people in her community fell ill. One woman died of cancer; another succumbed to kidney disease. Ramos can’t be sure dirty water was to blame, but she is suspicious and continues to buy bottled water for drinking and cooking. And it is not cheap. Buying water at the market costs her some US$30 a month on top of her approximately US$130 a month tap water bill — not to mention the time lost in making the weekly trips. The financial challenge became even greater last November, when she was laid off from her agricultural field work. Her employer told her that she would be back to work by March or April, but when the time came she was told not to return due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

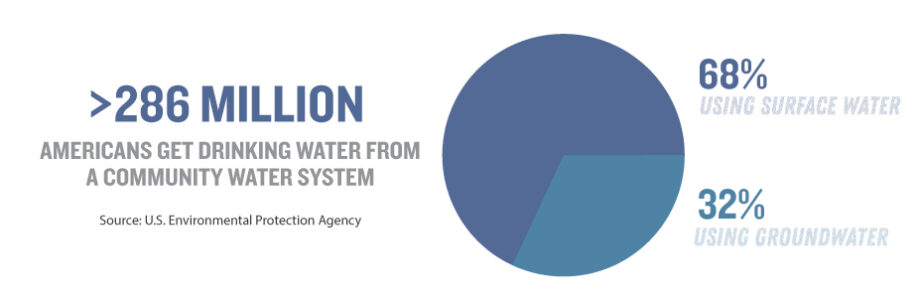

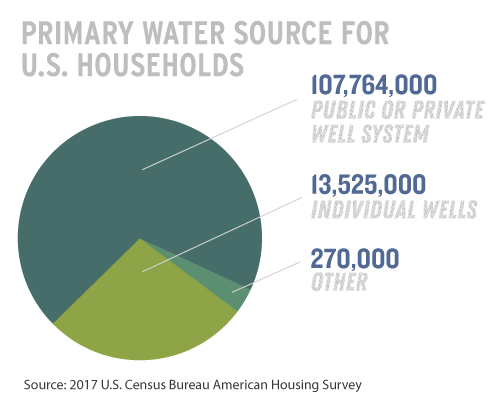

Across the U.S., drinking water systems serving millions of people fail to meet state and federal safety standards. Millions more Americans may be drinking unsafe water without anyone knowing because limits set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) are too high, the contaminants it contains are unregulated, or their drinking water source is too small to fit under EPA regulations. (An estimated 20% of private wells, which fall outside EPA regulation, have contaminants that exceed EPA standards.) The nitrate and disinfection by-products that worry Ramos represent a fraction of the many chemical and biological pollutants that find their way into drinking water systems through agricultural runoff, discharges from industry, aging pipes and all the stuff that flush down our toilets, sinks, showers and washing machines. From coast to coast, people are starting to recognize the pervasiveness of potential problems and rally around efforts to make drinking water safe for all.

“By and large, water quality in the U.S. is some of the best in the world,” says Maura Allaire, a water economist at the University of California, Irvine. Modern management and treatment technologies provide clean water for most Americans. Yet in a given year, between 7% and 8% of community water utilities report at least one health-based violation of federal standards, according to her research.

“How can we help those falling through cracks?” Allaire asks.

In 2015, Flint, Michigan, made headlines when a change in its water supply exposed thousands of children to high levels of lead, a neurotoxic metal. The tragedy led other communities around the country to take a closer look at their own drinking water quality. Many places, such as Newark, New Jersey, have since discovered dangerously high lead levels, too.

Meanwhile, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFASs — difficult-to-destroy chemicals widely used in nonstick pans, stain-resistant carpets and firefighting foam — have infiltrated major water supplies and grabbed headlines across the country as potential carcinogens and endocrine disruptors. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently issued a statement warning that exposure to high levels of PFAS might also suppress the immune system and raise the risk of infection with Covid-19. The CDC further referenced evidence from human and animal studies that PFAS could reduce response to vaccines — on top of posing a number of other health threats.

Plastics, pesticides and pathogens also fall on the long list of threats to safe drinking water.

Between 10% and 15% of Americans are on private wells or tiny water systems that serve fewer than 15 residences. The rest of the country relies on community water systems — upwards of an astounding 50,000 in total.

The first water pipes under America’s streets were not necessarily laid for the purpose of drinking, eating or bathing.

Beginning in Boston in the mid-1600s, cities constructed water systems primarily for fire protection. “Urban infernos were a real concern,” says Greg Kail, director of communications for the American Water Works Association (AWWA), the largest trade group for water supply professionals.

Most systems were ultimately adapted to supply water to commercial and residential properties. And, in the early 20th century, the practice of filtering and disinfecting water began. Untreated water supplies had been sickening people with pathogens like typhoid and cholera. “One of the miracles of the 20th century is that drinking water treatment decreased mortality, including from a host of afflictions people didn’t even realize were related to water,” says David Sedlak, an environmental engineer at the University of California, Berkeley.

But disinfection had a down side, too. In the 1970s, researchers discovered that a commonly used disinfectant, chlorine, could produce harmful by-products under some circumstances. Chronic exposures to these by-products have been linked in animal and epidemiological studies with liver, kidney and nervous system problems, as well as a potential increased risk of cancer. “But it’s important that we don’t stop using disinfectants because of fears of disinfection by-products,” says John Fawell, an independent drinking water consultant based in Slough, U.K. “The pathogens that can be in the water are still very able to cause significant problems.”

In the 1970s it also became clear that water was being polluted with contaminants that disinfectants were helpless against. Scientists were increasingly recognizing the threat of toxic chemicals from industrial sources, many of which posed risks over long periods of time as opposed to the acute effects of a waterborne illness. Congress enacted the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) in 1976, and in 1980 established the Superfund program, which focuses on cleaning up hazardous waste sites and so helps prevent drinking water supplies from becoming contaminated in the first place.

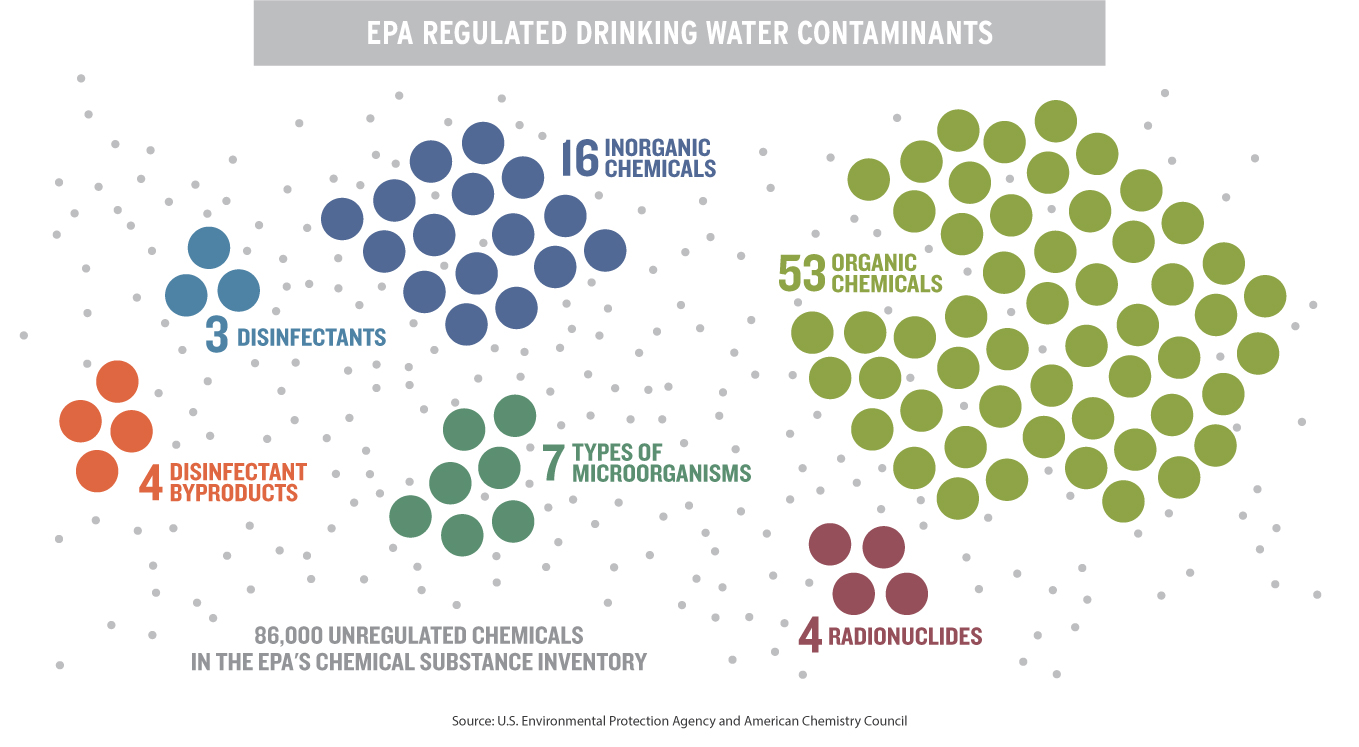

The key piece of legislation protecting our drinking water, however, is the Safe Drinking Water Act. Congress passed the act in 1974, through which the EPA now sets minimum health-based standards on more than 90 drinking water contaminants, including lead, nitrate, arsenic, disinfection by-products, pesticides, solvents and microbial contaminants. It is primarily up to each state to implement and enforce those standards — or set and enforce their own more stringent standards.

“Great progress was made,” says Sedlak. “But I think the more we study water supplies and the more stress that’s put on existing water supplies, the more problems we discover.” The EPA lists some 86,000 chemicals in its TSCA Chemical Substance Inventory — a number of which could find their way into our water in some way or another.

Seth Siegel, author of Troubled Water: What’s Wrong With What We Drink, underscores the evolution over time in contamination concerns, from the biological to the chemical. “A dab of chlorine might address microorganisms, but it does nothing about these synthetics,” he says. “We are ingesting, in micro quantities, a cocktail of chemicals all the time.”

Allaire lived in Lansing, Michigan, when the water crisis broke in Flint, about an hour northeast. Flint had just switched its water source from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department to the Flint River. The river water was slightly more acidic — and therefore more corrosive — than Detroit’s water. Local water officials didn’t use common corrosion control methods. As a result, lead and other pollutants began to leach from the pipes that distribute water to the city’s residents.

“We weren’t far away, and we were in a similar situation: a former industrialized city that had a massive exodus of its population,” she says. The tragedy led her to wonder just how far water quality issues extended beyond Flint. “Were there mini-Flints around the country, or was this a one-off event?” Allaire asks.

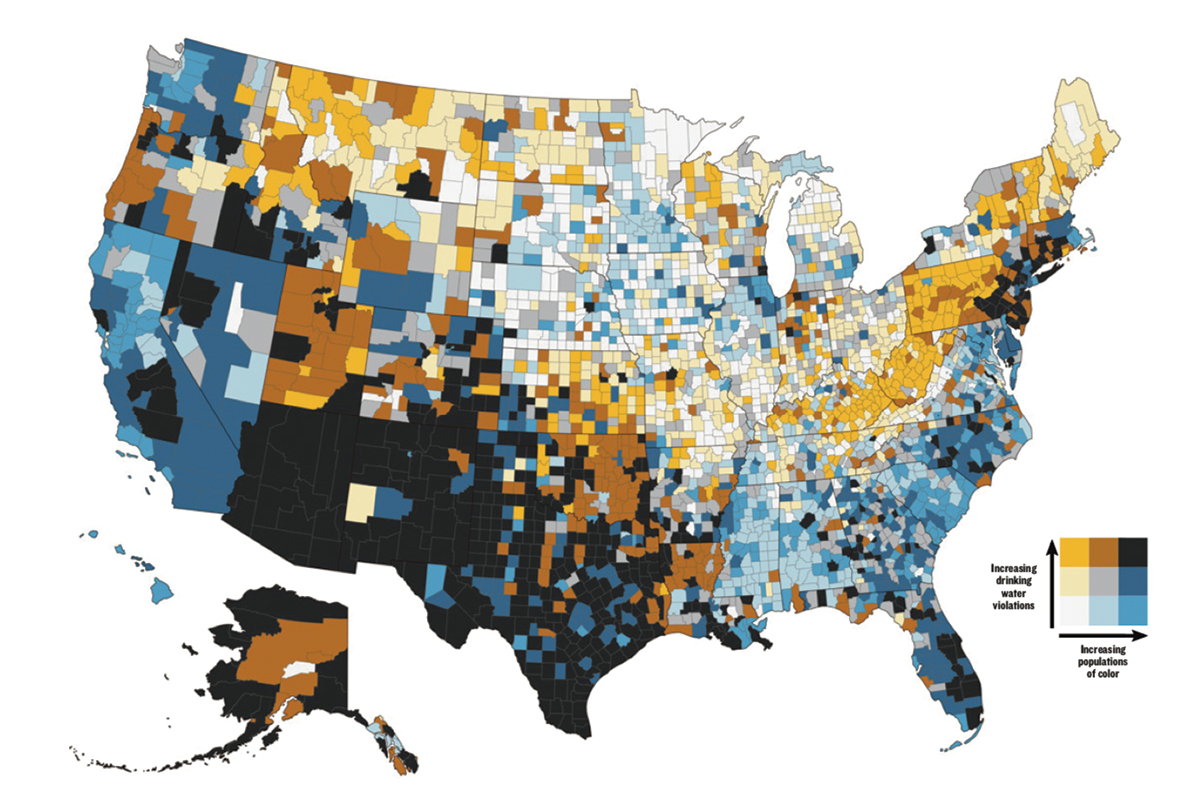

The answer, according to her 2018 study, is clearly the former. In 2015, the same year that the nation learned of Flint’s lead contamination, she found that about 21 million other people in the U.S. were receiving water from utilities that violated the Safe Drinking Water Act. People who lived in rural, low-income areas seemed to be most at risk of exposure to contaminants linked to a range of health problems — from a bout of diarrhea to cognitive impairment or cancer. “As we saw in Flint, and have seen repeatedly across the country, nine out of 10 violations don’t face any formal enforcement action by the state or federal government,” says Erik Olson, senior strategic director for health and food at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). “What we have is comparable to everyone on the interstate speeding and virtually no one being pulled over or getting tickets with any penalty.”

Even when the law is enforced, advocates lament that the standards used are often outdated. The current federal drinking water standard for nitrate, for example, went into effect in 1992 at 10 parts per million. Yet research has found that levels less than one-tenth of that legal limit may raise the risk of cancer and other health issues. In early 2019, the EPA suspended plans to reevaluate the nitrate standard.

The EPA did propose an update in October 2019 to its rules on lead and copper, which had not been touched since 1991. Meanwhile, the House of Representatives approved new legislation this past July that authorizes US$22.5 billion to replace a portion of the country’s estimated 6 to 10 million lead service lines that remain, connecting water mains to homes in Flint, Newark and elsewhere. Kail says that AWWA supports the revision. “As long as there is lead in contact with the water, some level of risk remains,” he says. “So the best cure is to get the lead out.”

Advocates argue the rules still won’t go far enough or come fast enough. And they suggest the same generally holds for the EPA’s actions or inactions on drinking water quality. Of most concern, they say, are the potentially hazardous contaminants that still lack a standard. “The law really is broken and needs to be fixed if it is going to protect the public,” says Olson.

The EPA’s current process for developing new standards, defined in the 1996 amendments to the Safe Drinking Water Act, needs to be sped up and strengthened, he and other advocates say. The EPA’s Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR) allows the EPA to select up to 30 unregulated pathogens and pollutants to be monitored every five years. Public drinking water systems serving at least 10,000 people, along with a representative sample of smaller systems, must periodically test for these contaminants. The agency uses the data in considering future drinking water standards.

So far, the only new chemical that the agency has come close to regulating through the process is perchlorate, a component of rocket fuel, munitions and fireworks. Studies suggest that exposure may derail brain development of fetuses and infants. The EPA determined in 2011 that the contaminant required regulation. But this June, the agency reversed course and announced that, taking into consideration “the best available science and the proactive steps that EPA, states and public water systems have taken to reduce perchlorate levels,” it would not regulate perchlorate. That decision is now in litigation. “The EPA just hasn’t had the spine to issue any regulations off the contaminant candidate list,” says Olson.

Six perfluorinated chemicals were monitored via the UCMR between 2013 and 2015. This past February, the EPA announced preliminary regulatory determinations and opened up comments for two of those chemicals, PFOA and PFOS. Meanwhile, several states, including New Jersey and New Hampshire, have moved ahead with their own regulations, some of which go beyond PFOA and PFOS — the legacy PFAS compounds that are already being phased out — to include more of the potentially thousands of extremely persistent synthetic chemicals that belong to the same class.

Philippe Grandjean, a professor and environmental medicine research unit head at the University of Southern Denmark and adjunct professor of environmental health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, warns of a potential regrettable replacement problem. “We see other PFASs popping up,” he says. “Which do you prefer, a devil you know or a devil you don’t know? It looks like we’re currently regulating so that we’ll get more devils that we don’t know. And it could well happen that some of those devils may act together to be even more hazardous than those we banned.”

Pathogens remain a serious issue, too. E. coli in drinking water has caused deadly outbreaks. Norovirus, Giardia and cryptosporidium have also contaminated drinking water supplies in recent years. But the pathogens perhaps highest on the minds of experts today are those that grow in pipes.

Legionella, the bacterium that causes Legionnaires’ disease, a type of pneumonia, offers a critical case in point. It poses a microbiological threat with widespread consequences. In Flint, the same issue that caused the release of lead into the drinking water also resulted in deadly cases of Legionnaires’ disease in the surrounding community. Repeated outbreaks at a Quincy, Illinois, veterans home have killed more than a dozen people since 2015. And, in May 2019, a custodian died from Legionnaires’ disease after being infected at Kettering Fairmont High School in Kettering, Ohio. The school’s water tested positive for Legionella this July, and a current custodian has tested positive for the disease. Spokespeople with the Illinois veterans home and the Ohio high school note that measures have been taken to reduce the risk of further infections.

When buildings go unused for long periods of time, stagnant water can become a breeding ground for the bacteria. “The big problems are when you have water that sits a long time without chlorine. Legionella love that and reproduce and bloom,” says Olson. “With schools and all sorts of other commercial and other buildings where water has been sitting for a long time with little use, it could be a massive problem. That’s a real worry post-Covid.”

Agricultural practices remain implicated in much of the nation’s tainted drinking water. Studies have shown that pesticides pose a serious threat. For example, atrazine has been associated with low birth weight in babies.

“Every spring in the Midwest, a pulse of atrazine comes off the fields. Tough luck on you if you happen to be carrying a child during that period,” says Sedlak, noting that regulatory standards might still be met because EPA regulations average numbers over the course of an entire year.

Neonicotinoids are another example. “Neonics are wonderful [from a human health perspective] because they target receptors specific to insects,” Sedlak says. “But, after a chemical reaction with chlorine, the product is something that is likely to target people.” Limited data hints at potential health effects ranging from respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological issues to birth defects.

Excess fertilizer applications on farms also trigger major algal blooms that can contaminate drinking water. Toxins produced by blue-green algae (also known as cyanobacteria) in Lake Erie fed by runoff from farms in the watershed contaminated the Toledo, Ohio, drinking water system in the summer of 2014. Almost half a million people were told to avoid drinking, bathing or cooking with their tap water for a couple of days; 110 people got sick. It was neither the first nor the last time that such toxins threatened public health. Residents of Carroll Township, Ohio, received a similar warning in September 2013. And in July 2018, authorities in Salem, Oregon, advised children and the elderly not to drink the city’s water.

When Duane Munsterteiger’s 1-year-old son got sick with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in 1993, the idea that his family’s drinking water could be to blame didn’t cross his mind. “It was the most beautiful tasting water you’d ever want,” says Munsterteiger, of Ogilvie, Minnesota.

But subsequent tests of the water from his well found high levels of nitrate, which research suggests may be associated with respiratory infections such as RSV.

In addition to drilling a new, deeper well to supply his home, Munsterteiger also has adopted a number of environmental conservation practices in his farming. He uses cover crops and rotates his cows to graze different sections of his land, improving the health of the soil and minimizing runoff, and thereby reducing the nitrate that seeps into the groundwater. He knows that groundwater could become the water that his family members, and his cows, drink. “Good clean water is important for our animals, too,” Munsterteiger says.

Targeting the source of contaminants is a particularly effective way to tackle dirty water. This might mean using cover crops to limit agricultural runoff, as Munsterteiger did, or preventing the discharge of industrial chemicals.

The Clean Water Act, in theory, regulates discharges into U.S. waters and therefore protects sources of drinking water. However, this year the Trump administration issued a new regulation, the Navigable Waters Protection Rule, that narrows the scope of the Clean Water Act by revoking federal protections for millions of miles of streams and millions of acres of wetlands. The NRDC and other environmental groups have filed a lawsuit to stop the decision.

“If we don’t have a strong Clean Water Act, we’ll never have clean drinking water,” says Lynn Thorp, national campaigns director for the nonprofit Clean Water Action. “We need to put equal effort upstream.”

In this regard, too, some states are stepping up to fill in the gaps. Munsterteiger is among farmers participating in the Minnesota Agricultural Water Quality Certification Program, which offers incentives, including financial assistance for practices such as cover cropping, that can reduce the flow of agricultural pollutants into waterways. Other techniques to prevent contaminants from sullying source water include installing wood chip bioreactors on farms to reduce nitrate pollution.

Allaire and other water experts suggest further strategies for reducing drinking water threats, such as increasing funds for the EPA to more quickly identify and regulate contaminants and upgrading water systems infrastructure. They also underscore the need for more technological solutions both at the drinking water source and during treatment, while expressing concern that today’s technologies — from carbon-activated filtration to reverse osmosis — are not being fully leveraged.

Joel Ducoste, a professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at NC State University, underscores one key challenge: Many of the emerging contaminants of concern for drinking water, such as PFAS, were previously unknown. “We didn’t know it was there, so we didn’t engineer systems to be specifically effective in their removal,” he says. “We’re learning a lot now, working on chemical methods as well as biological methods to see how we might try to remove some of these compounds.”

It tends to be the small systems that lack the means to install or even maintain operation of the latest treatment technologies. Lanare, a small unincorporated community outside of Fresno, California, received more than US$1 million from the state to install a treatment plant to remove the arsenic that had chronically contaminated its drinking water. The facility was built but only stayed online for about six months before the community had to abandon it. “It wasn’t affordable over the long term to keep it up,” says Ryan Jensen, the community water solutions coordinator for the Central Valley–based Community Water Center.

Contaminated drinking water disproportionately affects small water systems, which serve predominately rural, low-income communities with relatively high percentages of people of color. Sometimes those systems can’t even afford the salary of a full-time operator. Florencia Ramos’ hometown of El Rancho has only 65 people. The city of Lindsay has just over 13,000. “A lot of these folks are farmworkers, who are [unwittingly] helping to poison themselves,” says Anne Schechinger, a senior analyst with the nonprofit Environmental Working Group (EWG, a partner in this reporting project).

There is now a push to build economies of scale so small systems don’t have to go it alone. Kentucky has been a leader in water system consolidation. The state has gone from more than 3,000 systems in the 1970s to fewer than 800 systems in 2018. But such consolidations don’t always go so smoothly.

Just a few miles down the road from El Rancho is Tooleville. For a long time, the small town dealt with high levels of nitrate. Other contaminants include hexavalent chromium, the compound that garnered notoriety from the movie “Erin Brockovich.” Tooleville has been trying for years to connect its water system with that of the neighboring city of Exeter. But they’ve run into political pushback. Exeter voted last year to reject Tooleville’s plea and has tabled the talks.

“Unfortunately, that’s not unique,” says Michael Claiborne, an attorney at the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability in Sacramento. “Few consolidations have gone smoothly. I’ve seen a lot of situations where politics are a barrier, and there’s an unwillingness to serve nearby communities.” He notes that more than 90% of Tooleville residents are Latino, while the city council of Exeter is 100% white.

Benjamin Cuevas, a resident of Tooleville, says that he and his wife, Yolanda Cuevas, have been careful to make sure their three daughters and two grandchildren do not consume any of the water out of their taps. Yolanda Cuevas rinses the kids down with bottled water after they shower. And she insists that they also use bottled water to brush their teeth.

The Cuevases and Ramos have different problems, but they share a lot of same concerns — and aspirations.

“I wish a lot more could be done so that we could have clean water,” Ramos says. She adds another important strategy to improve drinking water quality: “I urge people to be involved, to go to meetings, to give your input.”

“I hope we can get this solved soon,” Benjamin Cuevas says. “These problems have been going on a long time.”

Credits

Edge is the multimedia storytelling platform of Ensia, an independent, nonprofit magazine presenting new perspectives on environmental challenges and solutions to a global audience.

Story – Lynne Peeples

Lynne Peeples is Seattle-based freelance science journalist, specializing in the environment, public health and medicine.

Editing and Project Management – Mary Hoff

Mary Hoff is Ensia’s editor in chief.

Photo Research and Graphic Design – Sean Quinn

Sean Quinn is Ensia’s graphic designer.

Web Development – Dustin Carlson

Dustin Carlson is Ensia’s lead web developer.

Data Assistance

Environmental Working Group

Project Oversight – Todd Reubold

Todd Reubold is Ensia’s publisher, director and co-founder.

Proofreading – David Doody

David Doody is Ensia’s senior editor.

Fact Checking – Elise Bernstein

Elise Bernstein is Ensia’s communications assistant.

Interview Coordination – Jerry Jimenez

Jerry Jimenez is communications manager for the Community Water Center

Published September 15, 2020