March 26, 2019 — For many consumers, palm oil has become synonymous with environmental devastation in Southeast Asia. The industry has brought mass deforestation to the region, shrunk orangutan habitat beyond recognition and compromised local livelihoods. Indonesia, in the process, rose to become the third-largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a partnership between stakeholders in the palm oil industry, such as producers, retailers and NGOs, was created over a decade ago to make the industry more environmentally and socially responsible. It helped, but critics argue the industry is still a long way from sustainable.

Meanwhile, the palm oil industry has grown in other parts of the globe. Latin America, for example, has seen an uptick in palm production. And over the past decade or so, large-scale palm oil production has expanded into West and Central Africa. While some people have welcomed this in hopes it will bring economic opportunity, a number of communities are trying to resist — either the presence of the industry itself or the way individual companies operate in their countries. How these efforts play out could determine whether the industry can find a way to be more sustainable in Africa, and also the fate of communities across the continent, not to mention that of nonhuman primates.

“Palm oil companies will not just displace [people in affected communities], but their culture, their history, their value, their traditional institutions, will all be completely altered,” says Alfred Brownell, founder of the Liberian lawyers network Green Advocates and currently a distinguished scholar in residence at Northeastern University School of Law in Boston. He lives in the U.S. in exile out of fear for his life, after he says he was threatened by private security guards protecting land being cleared of sacred sites to make way for palm oil development in Liberia. But he has represented indigenous communities in Liberia’s Sinoe County, where residents say that since the palm oil company Golden Veroleum Liberia (GVL) arrived in 2010, crops have been destroyed, shrines desecrated, burial grounds and grave sites denigrated, rivers diverted or dammed, and precious wetland areas polluted.

“It was a fertile ground for growing vegetables and other food staples to complement our local food basket,” Brownell wrote in a letter to RSPO on behalf of residents. “All of these are no more. All of the swamps within our communities have been filled in to make way for oil palm.”

Unlike in Indonesia and Latin America, oil palm is native to West Africa, and an important traditional crop with a variety of uses. Here, a woman pours processed palm oil into a glass bottle in Masethele village, Bombali District, Sierra Leone.

Photo courtesy of Aubrey Wade | Namati

Liberia is home to the largest remaining tract of West Africa’s Upper Guinean forest, which has some of the richest biodiversity in the world. In addition to wetlands and farmland that communities depend on, the forest is threatened by expanding palm oil production, among other commercial activities. If it disappears, Brownell says, so too does the spiritual connection that many indigenous communities have with it. “That’s why we took this complaint before the roundtable,” he says.

Rising Demand, Growing Industry

Palm oil production continues to grow steadily throughout the world. “Production has been doubling worldwide every 10 years during the past 40 years,” says Thomas Mielke, CEO of the market analysis firm Oil World. “Palm oil has become the most important vegetable oil worldwide.”

That’s because it’s cheap, and there are more uses for it all the time. It’s in all kinds of packaged food, from crackers to ice cream to instant noodles, and the rapidly growing consumption of processed foods globally is a big reason for the exploding demand. It’s also used in soap and cosmetics, in biodiesel, and as a mineral oil replacement. And because it is a very productive crop, impacts on land use could be even greater if the world were to try to replace palm with a different vegetable oil.

In Africa, an estimated 3 million hectares (almost 7.5 million acres) of land “traditionally used or inhabited by local communities,” covering both forest and farmland, have been acquired by palm oil companies, according to Devlin Kuyek, a researcher with GRAIN, a nonprofit that supports small farmers. That’s in line with reporting from The Economist in 2014, when the magazine reported, “In the past decade, politicians in west Africa and countries of the Congo basin have leased out around 1.8m hectares [4.5 million acres] of land for palm-oil plantations, according to Hardman, a London-based research company. Another 1.4m hectares [3.5 million acres] is being sought. Foreign companies sniffing around include groups such as Wilmar, Olam, Sime Darby, Golden Veroleum and Equatorial Palm Oil.” Meanwhile, pointing to statistics from the nonprofit Proforest, The Guardian reported in 2016 that “[a]s much as 22m hectares (54m acres) of land in west and central Africa could be converted to palm plantations over the next five years.”

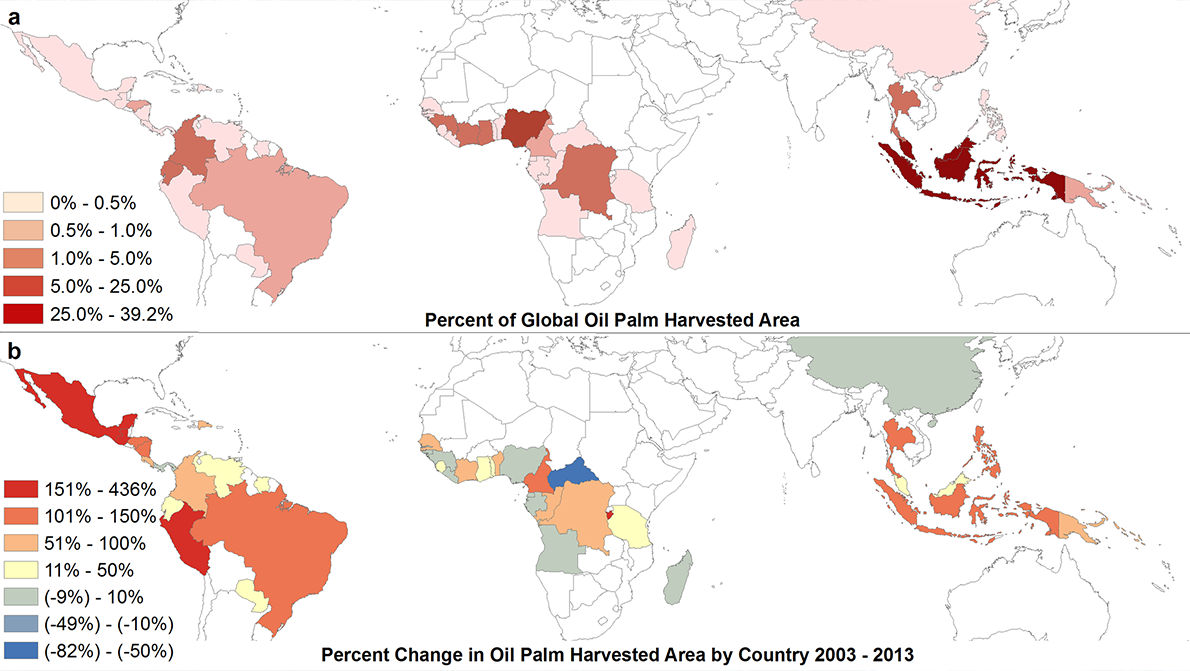

World production of palm oil. (a) Percent of Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)-reported total global oil palm harvested area in 2013. (b) Percent changes in FAO-reported oil palm harvested area by country, 2003–2013. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159668.g001. Source: Vijay, V., Pimm, S. L., Jenkins, C. N., & Smith, S. J. (2016). The impacts of oil palm on recent deforestation and biodiversity loss. PloS One, 11(7), e0159668. Click image to enlarge.

While exact numbers on future large-scale expansion are difficult to predict, the industry is undoubtedly growing. “Despite having little plantation area currently, some countries in Latin America and Africa experienced greater percent growth during [2003–13] than did either Indonesia or Malaysia,” researchers wrote in PLOS One in 2016. “If these growth rates continue, oil palm plantation expansion in these countries will likely have increased impacts.”

Toward Sustainability

From Liberia to the Democratic Republic of Congo, a battle has been emerging in recent years over where and how palm oil should be developed. There are concerns about impacts on local water supplies, wildlife populations, biodiversity and climate change. But the heart of the matter, what’s making communities speak out en masse, is control over land. To expand their palm oil production, a number of companies have relied on what critics describe as land grabs.

Communities aren’t opposed to growing oil palm. Unlike in Indonesia and Latin America, oil palm is native to West Africa, and an important traditional crop with a variety of uses. But in the past it has grown wild or been integrated into fields with other crops. The large global producers rely on monoculture plantations.

The RSPO was established in 2004 to create environmental and social standards for the palm oil industry. A number of environmentalists and human rights groups, however, have criticized it as ineffective or not effective enough. One study that evaluated a set of sustainability metrics on palm oil plantations in Indonesia found no difference between plantations that were RSPO-certified and those that were not. Another found that certification was sometimes associated with lower rates of deforestation, but many plantations were in areas where much of the forest had already been destroyed.

In this forest in Cameroon, oil palm planting is noticeable where diverse trees switch to monoculture. Photo courtesy of Mokhamad Edliadi | CIFOR

Brands that use palm oil, meanwhile, use the certification to assure customers that the ingredient is sustainable. “They talk a great talk, but they’re all basing their sourcing on RSPO certification,” says David Pred, executive director of Inclusive Development International, a nonprofit human rights organization. He adds, though, that all the negative attention to the RSPO has prompted some improvements. “There’s some teeth to the mechanism now, which I don’t think was the case a couple years ago. But it’s definitely not a panacea. There’s still a lot of loopholes, and I think it does provide a veneer of credibility.”

In Africa, the very certification that’s supposed to ensure sustainability is actually responsible for communities losing more land than what will even be used for production, according to Kuyek. The RSPO, he says, incentivizes companies to include more land in their contracts than they will convert to plantations, so they can say they are setting aside a certain amount for protection. “In a kind of sinister way,” he says, “it actually encourages a larger land grab.” Asked if he sees any validity to the land protection statute along the lines of ecological conservation, Kuyek wrote in an email, “I’m afraid I don’t. There can be no meaningful programme for ecological conservation embedded in a fundamentally, destructive model of plantation agriculture.”

John Buchanan, vice president of sustainable production at Conservation International, a nonprofit that has been an RSPO member for over a decade, has heard similar concerns. For him, it points to the crux of the much larger, seemingly intractable issue of poverty. “I have heard that general concern raised, but not from communities where we’re working [in Liberia],” he says. “The biggest thing we’ve heard from communities is, ‘When can we get our palm oil and how fast?’ I think they’re really eager for what they perceive as the development opportunities that come with it.”

In an emailed statement, Elizabeth Clarke, global palm oil lead for WWF, wrote, “If properly implemented, the newly revised RSPO standard should help safeguard against land-grabbing, because it entails combined HCV [High Conservation Value] and HCS [High Carbon Stock] assessments, FPIC (Free Prior and Informed Consent) and consultation with communities and all other relevant stakeholders, prior to any new plantings.”

Kuyek points to a plantation in Gabon, part of which is RSPO-certified, where 72,000 of the 144,000 hectares (178,000 of the 356,000 acres) committed are for protection of high-value forest and other areas.

Last year, Lee White, a conservation biologist with Gabon’s parks agency, told National Geographic, “What we’re trying to do in Gabon is find a new development path where we don’t cut all our forest down but keep a balance between oil palm, agriculture and forest preservation.”

In an email, Dan Strechay, RSPO’s U.S. representative, acknowledged “land grabs and conflict with communities have occurred,” but said that in November 2018 the roundtable revised its set of standards known as the Principles & Criteria (P&C) that “goes further to ensure that communities have resourced access to independent advice and better documentation of FPIC procedures during the process. … To address potential land rights issues, the P&C requires documents which demonstrate legal ownership or lease, or authorized use of customary land. Under the new P&C, this may include documents other than the legal title which establish a right to land use. For communities without formal legal recognition of their land, but have resided on the land for generations, this will help to provide better protection of their land rights.”

There are no simple answers, and Buchanan emphasizes the importance of looking at the full picture and searching for ways to meet the many different, and sometimes conflicting, interests and needs at play. “How do we find that balance between conservation and their economic needs?” he says. “Our experience in Liberia shows us that strict sustainability standards, that does not necessarily save the forests or benefit local communities. If those communities can’t find a way to meet those aspirations and lead better lives — if they can’t get palm oil, they’ll just look for something else.”

Window of Opportunity

Daniel Krakue of Social Entrepreneurs for Sustainable Development, a nonprofit in Liberia, says the Liberian town of Plusunnie has probably been the most impacted by the palm oil company GVL. He says that water is polluted, land that had always been treated and farmed as a communal resource — as is common in Liberia — has been lost to palm, and areas where people used to go for hunting and trapping are gone. “They have converted all the land for plantation purposes,” he says. “Some of these families, they’re young and energetic, they see that as development. But when they get fired, they have to go back in the town, and the town is not habitable anymore.”

But because much of the land under contract in Africa hasn’t yet been planted, there is still opportunity for a different path forward for much of what could be the world’s next palm oil hub. And the community backlash has been swift in many areas.

GVL, which left the RSPO in 2018, did not respond to requests for comments, but Golden Agri-Resources (GAR), GVL’s primary investor and the world’s second-largest palm oil company, says GVL is subject to GAR’s social and environmental policy. In a statement sent in response to questions, the company says, “While there are complaints from some communities, GAR understands that for most of the areas where GVL operates, FPIC has been applied in accordance with RSPO guidelines and communities welcome GVL’s presence. Nevertheless, GVL has acknowledged the need to continuously improve its sustainability processes and has started to implement a Sustainability Action Plan, as announced by its CEO on 20 July 2018. GAR is committed to support GVL in this and has sent a technical team to Liberia in September 2018 to assist. GAR continues to provide support as required and will regularly assess GVL’s compliance with the GSEP [GAR’s Social and Environmental Policy]. The GVL case has been included in the GAR Grievance List which is publicly available and GAR is actively monitoring and tracking GVL’s progress.”

Krakue says the RSPO does more good than not. “Things would be absolutely worse off [without RSPO]. Even though the way they treated the complaints coming from Liberia was not satisfactory,” he says, “at least the RSPO serves as checks and balance for these companies.” But he and other advocates think there is a lot of room for improvement.

Out-Grower Model

In Sierra Leone, Namati, a nonprofit that works with grassroots legal advocates around the world to help communities demand enforcement of laws meant to protect them, helped a community win a court ruling in November that ordered a Singapore-based palm oil company, Siva Group, to return land to the community and pay hundreds of thousands of dollars in unpaid rent. In Makpele Chiefdom in southern Sierra Leone’s Pujehun District, Namati represented landowners who had lost vast amounts of land in a lease they weren’t made aware of until after it was signed by an acting chief for the region. They negotiated a new lease that reduced the amount of committed land from more than 30,000 hectares (74,000 acres) to 2,300 hectares (5,700 acres) and established an “out-grower” model. The specifics of this model vary from site to site, but typically the company operates some land as a plantation and also provides smaller plots of land on which local farmers can cultivate palm trees independently. It allows, in other words, for contract farming, rather than relying on one company to provide all the employment opportunities.

A farmer in Sierra Leone prepares to climb one of his palm trees to harvest the kernels, which will be processed into palm oil. Photo courtesy of Aubrey Wade | Namati

A number of community advocates think that this kind of out-grower scheme, though not perfect, may offer a path to palm oil development that is less destructive to the environment than it has been in Asia and more inclusive of local communities that can benefit from the development rather than be displaced by it.

Eleanor Thompson, a lawyer with Namati involved in the Pujehun District case, says the out-grower model “is arguably the best agribusiness lease in the country at the moment in terms of benefits to the inhabitants of the land and the environmental protection standards.”

Large-scale operations provide “work for only two or three months in the year, and if you have given all your land to the company, then you have nothing to fall back on,” says Sonkita Conteh, country director for Namati. With the out-grower model, “you still get the output the companies require, and at the same time you are also helping farmers.” They have jobs year-round, and the smaller farms don’t have the same impacts on water supplies or use chemicals as intensively as the large plantations do, Conteh says.

Sierra Leone passed a law in 2016 that requires companies investing in agriculture to create out-grower opportunities for small farmers. In Liberia, Krakue says discussions are also underway between companies and farmers to establish out-grower contracts.

Ryan Zinn, regenerative projects manager at Dr. Bronner’s, a for-profit company that makes soap and other personal care products, is a little more skeptical of the out-grower model, saying the farmers can only really benefit if there’s not a monopoly on the local market. Otherwise, if there’s a disagreement, over price or quality, for example, farmers can be left without a buyer.

“From a small farmer perspective, I think it only works well if there’s a decent amount of competition in the area,” he says. “If there’s only one mill in the area, it can get pretty dicey.”

For Brownell, it does come down to those brands that buy the palm oil for their products. Palm oil producers aren’t vulnerable to the kinds of consumer pressures that can be brought against more familiar brands through actions like boycotts.

For the RSPO’s part in supporting small farmers, RSPO’s Strechay wrote in his email, “As production increases in Africa, FPIC and smallholder inclusion are important factors to consider in the region’s sustainability debate. For sustainable palm oil to become the norm, solutions must be accessible at every link and level of the supply.” He added, “Smallholders rely on oil palm cultivation for their livelihood but suffer from lower yields and limited market access. This can be addressed by supporting smallholders to transition towards sustainable production and remains a top priority for the RSPO. This has led to the development of an additional and separate standard exclusively applicable to independent smallholders: the RSPO Smallholder Standard.”

In Ghana, about 600 farmers produce palm oil that they sell directly to Dr. Bronner’s. They grow on their own land or on land that they lease from, say, a neighbor — not on land controlled by the company — and can sell to any buyer they have access to, although Dr. Bronner’s pays premiums for fair trade and organic production. Zinn says the company is now working with farmers to add a more diverse, agroforestry-based approach to growing palm oil. A more diversified system, he explains, is more resilient against climate change and also provides more stability for the local economy.

But it’s also more expensive. Zinn estimates the price for Dr. Bronner’s to source this way is 10 to 20 percent higher than the commodity price for palm oil on the global market. That’s a choice Dr. Bronner’s has made, and while he thinks the model could be scaled, that can only happen if there’s a market demand for the higher-value oil. “Your costs of production are going to be higher, so long as a consumer is willing to pay for that, absolutely this model can be replicated,” he says. “The question is, is there that political or economic will to make it happen?”

For Brownell, it does come down to those brands that buy the palm oil for their products. Palm oil producers aren’t vulnerable to the kinds of consumer pressures that can be brought against more familiar brands through actions like boycotts.

“You’re never going to see them anywhere in the U.S.,” Brownell says, “but just walk into the supermarket and the food that you’re buying — the chocolates … the chips, the snacks — all have palm oil. These different brand names, Nestle, Mars and others, are the ones who are the major buyers.”

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

www.hcvafrica.com

Please also check out Palm Done Right - a response to the poor track record of the RSPO. Well-known ethical brands like Dr. Bronner's and Nutiva are on board.

https://ethicalbargains.org/2021/06/20/nutiva-shortening-ethical-review-palm-done-right/

More on the different levels of palm oil certification here:

https://greenstarsproject.org/2021/09/19/palm-oil-certifications-best-worst/