June 26, 2019 — Some 40 percent of America’s food goes uneaten, costing the nation some US$218 billion annually. Food waste is a major contributor to deforestation and water waste, and comes a close second to road transportation in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. It accounts for almost 3% of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., about the same as 37.4 million passenger vehicles driven over the course of a year.

Food waste has become a focus for environmental activists, and the dilemma has inspired a seemingly endless string of apps aimed at reducing it. Harnessing the power of technology to fight food waste may be an attractive approach. The question is, how do these apps hold up in practice?

Saving Food, Cutting Emissions

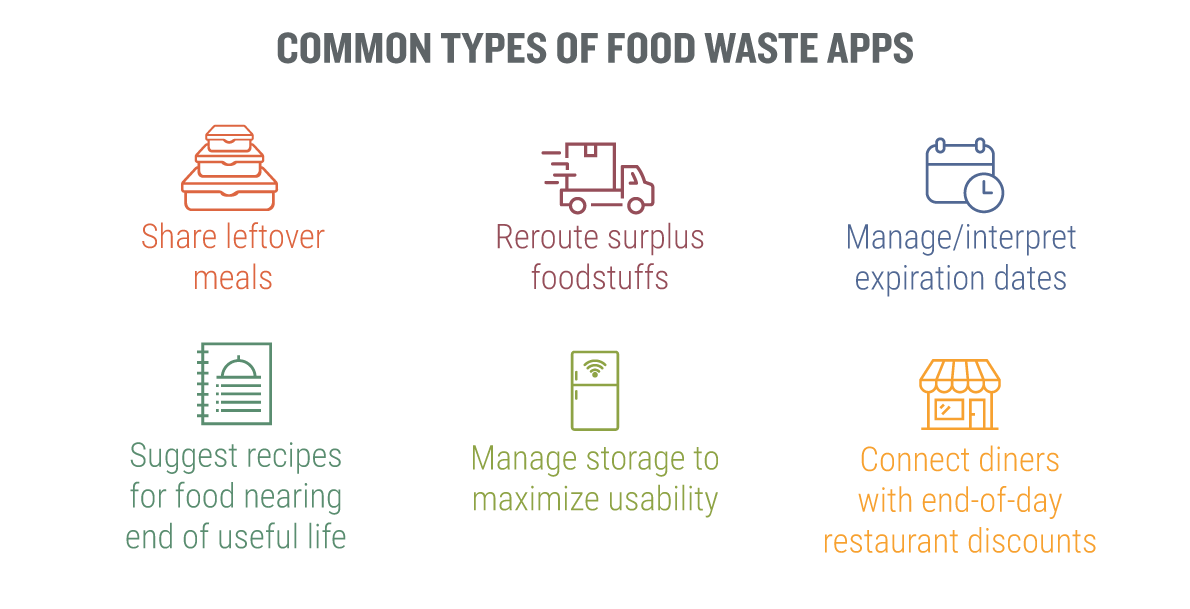

Food waste apps cover a wide range of strategies, tackling everything from sharing leftovers, to managing food once it’s purchased, to finding buyers for surplus supermarket produce, to offering diners end-of-day discounts on food remaining at restaurants. Most food-waste-related apps focus on food recovery — that is, salvaging food that would have otherwise been thrown away and distributing it to others.

Disturbed by the fact that some 40% of food in United States is thrown away while one in every eight Americans goes hungry, University of California, Berkeley, student Komal Ahmad created Copia, an app that transfers excess food from things like business events to soup kitchens, homeless shelters and food banks. Copia reports it has diverted 1 million pounds (500,000 kilograms) of perfectly good, uneaten food that would have otherwise been landfilled to food-insecure Americans.

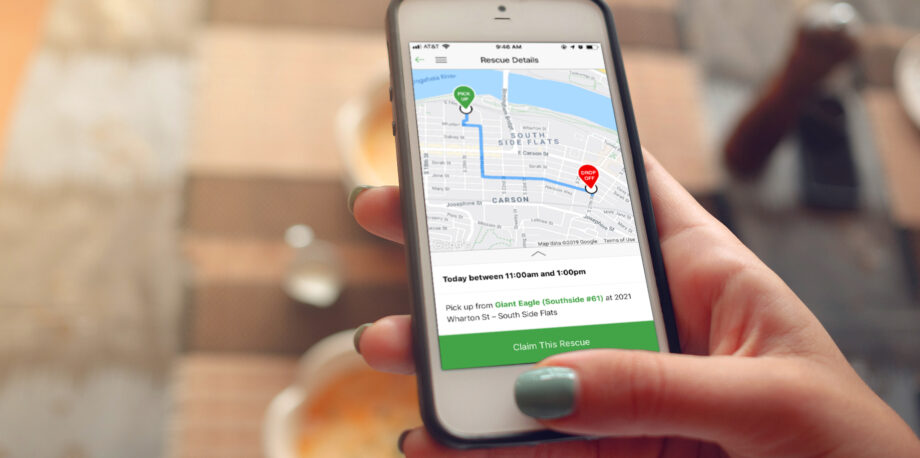

With help from an app that connects extra food with people in need via delivery volunteers, Food Rescue US has kept some 45 million of pounds from being wasted since 2011. Photo courtesy of Food Rescue US

In Pennsylvania, 412 Food Rescue reports it has saved more than 6 million pounds (3 million kilograms) of food, avoiding 3 million pounds (1 million kilograms) of carbon dioxide production. Food Rescue US, which has 22 sites around the country, reports saving more than 45 million pounds (20 million kilograms) of food in the past eight years.

“Ultimately, we’re here to reduce food waste,” says Anoushka Grover, marketing manager for Too Good To Go, an app connecting consumers to restaurants and retailers offering unsold food at a reduced price. “But that translates directly to the amount of [greenhouse gas] emissions we reduce.” Too Good To Go reports it has prevented 40 million kilograms (89 million pounds) in CO2 emissions.

Coming Up Short

While such apps have been tremendously helpful in diverting food and spreading awareness of the food-waste issue, they have some downsides, too. For one thing, they don’t address one of the main causes of food waste — societal norms.

“There are cultural expectations that we have about surplus,” says food-security activist Andy Fisher, author of The Big Hunger: The Unholy Alliance Between Corporate America and Anti-Hunger Groups. “There’s always extra food — you want there to be extra food — you don’t want to run out.”

“Getting food from A to B that’s about to go to waste is good, but wouldn’t it be better to not even have all that extra food to begin with?” asks Jordan Figueiredo, founder of EndFoodWaste.org and the “Ugly” Fruit & Veg Campaign.

“Getting food from A to B that’s about to go to waste is good, but wouldn’t it be better to not even have all that extra food to begin with?” asks Jordan Figueiredo, founder of EndFoodWaste.org and the “Ugly” Fruit & Veg Campaign.

Another issue is that there’s just no good way to measure the true impact of these apps in terms of reduced food waste. The companies measure the apps’ success through pounds of food moved. But once the food has been delivered, there’s no way of knowing what happens to it.

“They have no idea how much of the food recovered is actually consumed versus tossed by a food bank or recipient for various reasons,” says Ashley Zanolli, former senior policy and program advisor of the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and developer of the Environmental Protection Agency’s Food Is Too Good To Waste toolkit.

Zanolli also notes that, in the case of food donations, 1.2 pounds (0.5 kilograms) is considered a meal by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, regardless of what type of food — or beverage — it is. A company could technically donate 500 pounds (200 kilograms) of sauce and have it count as 417 meals.

“The apps are doing the best they can with calculating social impact; however, there are some serious flaws,” she says.

Misuse or misunderstanding of the app by clients is a common challenge, as well. Some think food sharing apps offer plate scraps rather than food that remains on the buffet table or in the kitchen. Establishments offering discounted food toward the end of the day are sometimes reluctant to use an app for fear that consumers would wait until closing time to get their favorite foods instead of dining during regular hours. Others are concerned about possible lawsuits (although the Good Samaritan Food Donation Act of 1996 protects donors from liability).

But the biggest issue seems to be scaling. Many food-waste apps, particularly those in North America, have limited reach. FlashFood, for instance, is currently only serving Canada and Wisconsin. BuffetGo is available in certain cities in California, Illinois, New Jersey and New York. Food Rescue US has what appears to be the widest reach, spanning 13 states and Washington, D.C.

Another way in which potential impact is limited is that most food-waste apps address food recovery — rerouting surplus food and leftovers from events. Far fewer help restaurants offer end-of-day discounts or address household food-waste issues such as managing perishables, leaving a window of opportunity that’s not being tapped.

Geography is also an issue. These apps work better in urban areas than the suburbs and rural areas because the population is dense, demand for deliveries is high and there are many drivers to make deliveries. As a result, rural areas have proven difficult to reach. To that end, Atlanta, Georgia-based app Goodr is working toward a partnership with UPS to pilot a program that ships food overnight from urban areas to rural food banks and homeless shelters.

“The technological solution for food waste is definitely helpful and apps and software connecting all different kinds of sectors are definitely needed,” says Figueiredo. “But is technology the solution? No, I don’t think it’s the solution.”

Nor, Fisher points out, is food waste redistribution a solution to food insecurity. But until the larger system is fixed, apps may be an important part of closing the gap between abundance and need.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!