February 8, 2019 — In the fall of 2016, when sixteen-year-old Edgar Cardoso walked into the squat, beige biorepository at the University of California, Berkeley, he couldn’t help but feel kind of special. Among the more than 1,000 human samples stored in barcoded vials in freezers — everything from saliva to umbilical cord blood — Cardoso knew some were his.

Seeing it all for the first time, he remembers telling himself, “This is a bigger thing than I thought.”

Since he was in utero, Cardoso has been part of the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas Study — the CHAMACOS Study for short, an acronym that means “little children” in Spanish. The study began in 1999, when Brenda Eskenazi and Asa Bradman — director and associate director, respectively, of UC Berkeley’s Center for Environmental Research and Children’s Health (CERCH) — became interested in shifting pesticide policy and received funding for community-based research in California’s Salinas Valley, an agricultural region often called the “Salad Bowl of the World.”

Through the samples at the biorepository, the CHAMACOS babies have helped CERCH researchers arrive at some concerning conclusions about childhood brain development and pesticide exposure.

Researchers found that women who had higher exposure to organophosphates during pregnancy were more likely to have children with neurodevelopmental disorders. This could mean infants with slower reflexes, toddlers who show autism-like disorders, five-year-olds with behavioral problems like ADHD, and seven-year-olds whose IQs, on average, are seven points behind their peers. Similar results were found in CHAMACOS’ sister studies — one based at Columbia University and the other at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, both in New York.

The CHAMACOS study was slated to end when the participants were toddlers, but its success so far and its strong community ties — the CHAMACOS office is based in Salinas and much of the team is from the region — have led to definite funding into the early 2020s.

That means the researchers don’t have to “parachute in and leave,” says Kim Harley, an epidemiologist at UC Berkeley and a CHAMACOS associate director. “It’s important for us to give back to the community as much as we take away from them.”

If geography is destiny, then Salinas was fated to be agricultural. Nestled between two mountain ranges along California’s Central Coast, its mild, Mediterranean climate is moderated by a cool Pacific breeze that flows from the coast to the crops.

While the research remains the primary aim of CHAMACOS — the team has published more than 150 papers — a large part of their outreach has been disseminating the study’s key findings to the public. Early on, the CHAMACOS team discussed what role prevention would play in their work. It seemed irresponsible, Harley recalls, to not educate families on pesticide exposure prevention. So the team began a yearly CHAMACOS forum where participants could learn about recent findings and ways to prevent pesticide exposure prior to reading about it in the news. At the forefront of this work is José Camacho, the CERCH community outreach coordinator. As a Salinas resident, native Spanish speaker and former farmworker whose wife still works in the fields, he is the perfect translator between the science and the reality it studies.

During the early years of CHAMACOS, when Camacho began speaking with farmworkers about pesticide safety, few people knew about the dangers of exposure. “Now most farmworkers — I don’t want to say everyone, but most — know a little bit about pesticide safety,” Camacho says.

The advice disseminated by Camacho at the annual forum, community events, and through free Spanish-language workshops across the state’s agricultural valleys is simple but significant, and is as much about protecting children as it is about protecting farmworkers themselves: Wash your hands before consuming food, shower before hugging or carrying your children, leave your work clothes and shoes outside the home.

Feedback from the community has been overwhelmingly positive. While Camacho has comforted many mothers distressed to discover they may have unknowingly exposed their children to potentially harmful effects of pesticides, he is often approached by farmworkers in Salinas and around the state, grateful to have learned more about pesticides and how to minimize harm to themselves and their families.

Getting Youth Involved

In a community where nearly one-third of the population is under 18 years old, the researchers wanted to involve youth in innovative ways, too. In recent years that desire has taken shape in the development of Youth Councils. Since 2010, there have been three Youth Council cohorts based in Salinas. The projects are modeled on the concept of Youth-led Participatory Action Research — an approach that involves youth in projects to address community problems and develop solutions. The first group undertook a photography project that included a series of talks about the way in which issues such as pesticides and access to healthy food influence health outcomes in Salinas. The second group focused on chemical exposures through personal care products such as makeup. When the latter project ended in 2015, Harley and the CERCH team realized the timing was perfect.

“We went, wait a minute,” Harley says. “The CHAMACOS kids are 14 years old now and we’re looking to enroll a bunch of 14-year-olds.”

In early 2016, about a dozen of the original CHAMACOS participants, including Cardoso, were recruited to join the third CHAMACOS Youth Council. The group decided to study pesticide exposure among teenage girls across the Valley and called the project “Chamacos of Salinas Evaluating Chemicals in Homes & Agriculture,” or COSECHA, “harvest” in Spanish.

But the Youth Council is not only about studying pesticides. It has also become a way for the young people involved to see themselves and their home in a different light. Given Salinas’ agricultural landscape, pastoral settings may easily come to mind for people unfamiliar with the area.

“They just didn’t know. Nobody knew. There was so much we didn’t know about the effects of pesticides on children’s development.” –Kim Harley

But from her childhood bed in the living room of her parents’ one-bedroom home in East Salinas, Daisy Gallardo, another Youth Council participant, remembers hearing gunshots and sirens screaming in the night. Her high school banned certain colors and sports merchandise because of their affiliation to local gangs. And in 2015, for the fourth time, Monterey County, where Salinas is located, was ranked the youth homicide capital of California. To grow up here young, poor and Latino, defined by your hometown’s violent reputation, means opportunity doesn’t often knock.

So, the Youth Council is as much about empowering young people as anything. “There are a lot of good things happening here that people just don’t get to see,” Gallardo says. “Being youth involved in science is not only helping us but the entire community.”

“Could it be the pesticides?”

If geography is destiny, then Salinas was fated to be agricultural. Nestled between two mountain ranges along California’s Central Coast, its mild, Mediterranean climate is moderated by a cool Pacific breeze that flows from the coast to the crops. The fields here cascade in impossibly straight rows of strawberries and lettuce and surround everything, including the CHAMACOS office based at Natividad Medical Center.

In this kind of agricultural economy, pesticides are also pervasive.

In the late ’90s, when Eskenazi and Bradman arrived in the Salinas Valley, about a half-million pounds of organophosphate pesticides were being used in the region each year. In the 1970s, organophosphate pesticides, which operate in a similar way to the military nerve gas sarin, was adopted by farmers as a safer alternative to DDT following the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal book, Silent Spring, and DDT’s subsequent ban. While farmworkers, including pregnant women, picked, packed and handled produce every day, researchers knew little about the effects of chronic, low-dose exposure to organophosphates. But, as Harley recalls, the community was concerned. They spoke of moms with cancer and children with ADHD, asking, “Could it be the pesticides?”

“They just didn’t know,” Harley says. “Nobody knew. There was so much we didn’t know about the effects of pesticides on children’s development.”

The majority of the 601 expectant mothers enrolled in the CHAMACOS study were Mexican immigrants who were low income and either worked in the fields during pregnancy or lived with someone who did. Cardoso and Gallardo were among the group of children born to these women. Every one to two years they would go to the CHAMACOS office for a series of lab tests, MRIs and cognitive exercises, depending on their age. With each activity, there was an underlying question: Could pesticides have harmed this child’s brain?

“Although I can’t tell you that organophosphates specifically cause neurodevelopment problems or delays in children,” Harley says, “I can tell you that we have quite a strong body of evidence now linking those two things. It sort of becomes, at what point do we have enough evidence to be concerned. And enough evidence to take action?”

Members of the CHAMACOS Youth Council collect dust samples from homes involved in their study. Photo courtesy of Brenda Eskenazi/CHAMACOS study

While science nor policy are known for the speed with which they work, California has seen some substantial changes. Since CHAMACOS began, use of organophosphates in the state has dropped by about 60 percent. According to Nolan, “the development of new California Worker Protection Standards included review of CHAMACOS research, with new regulations preventing those who are under 18 years of age from handling agricultural pesticides.” More so, when pesticide regulations have been proposed for the state, such as the Pesticide Use Near Schoolsites regulation, which was adopted in early 2018, CHAMACOS researchers have written public comments and given expert testimony based on the team’s findings.

But there remain challenges. In early 2017, former U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administrator Scott Pruitt rejected a petition from health and environmental groups to ban the organophosphate pesticide chlorpyrifos. Nearly 20 years ago, the pesticide was banned for home use, but is still widely used in agriculture with more than 900,000 pounds (400,000 kilograms) used in 2016 in California alone. In August 2018, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco ordered the EPA to remove chlorpyrifos from sale in the U.S. within 60 days. In September of that year, the Department of Justice requested that the Ninth Circuit reconsider its decision. While the chlorpyrifos case is an example of the slow pace of regulatory change and the political nature of such issues, it has also helped highlight the use of agricultural pesticides in the U.S.

“The attention that chlorpyrifos is getting right now is not something we were seeing 20 years ago,” says Harley. “I think there is more awareness now, even on the national level.”

Youth Involvement

When Cardoso thinks back to the first Youth Council meeting in January 2016, all he can remember are the nerves. Since childhood, he has struggled with a stutter. While his speech has improved, Cardoso was worried that his nervousness would cause the words to stick in his throat.

“I don’t want to say something and screw up,” he remembers thinking at that first meeting. “So I just won’t say anything at all.”

And Cardoso wasn’t alone. The entire group was essentially silent at their first Youth Council meeting. So, James Nolan, another CERCH community outreach coordinator who facilities the youth council, decided that for the first six months of the three-year project the group members would learn through public speaking. Each week, a Youth Council participant would present an environmental health topic to the group to learn about science communication and build confidence. For the shyer participants in the group, it seemed to work. Like Cardoso, before joining the Youth Council, Gallardo was afraid to speak in front of people, she says. By the end of high school, she had presented on COSECHA to everyone from the Monterey County agricultural commissioner to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

“I always think of these studies with the Youth Council as having two levels,” Harley says. “There’s the actual study that has scientific goals and then there’s this sort of meta goal, which is that we’re training a group of youth to do public health research and think about ways to communicate problems in the community.”

In the Field

In the summer of 2016, the CHAMACOS Youth Council began collecting data for its COSECHA study. The team enrolled 100 teenage girls in the study, all of whom were also CHAMACOS participants. They then spent two months visiting each home to collect information. They requested a urine sample from each participant, took an inventory of pesticides such as bug spray and weed killer, noted if the house had a doormat, and identified what kind of crops were grown in nearby fields. The team also used chemical sampling wristbands, identical to the kind of silicone bracelets sold at charity events, to measure an individual’s exposure to different environmental chemicals. For one week, each participant wore the wristband and a GPS device.

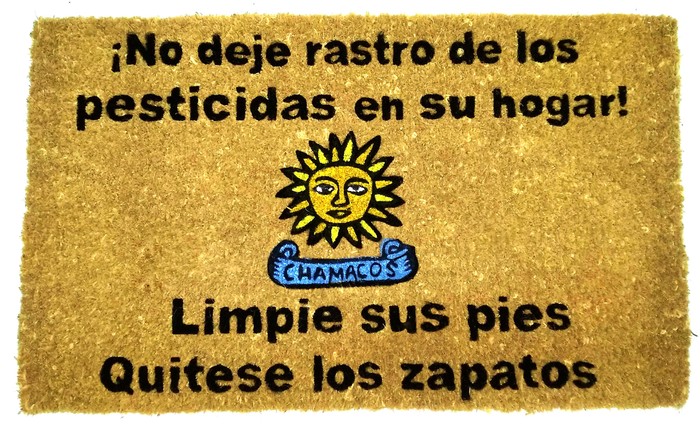

In October 2018, the CERCH team published the first COSECHA paper, detailing the findings from the wristband data. The wristbands detected some 25 pesticides, including chlorpyrifos and several “legacy pesticides,” some of which have not been used for more than four decades. One of the major findings, related to mitigating exposure, was that participants whose homes had doormats also had lower pesticide exposure. “Much lower,” Harley says. “Which is so funny because it’s such a simple thing.”

Researchers found that homes with doormats had lower pesticide exposure, so as part of their community outreach, the Youth Council designed a doormat with a message in Spanish to “wipe your feet and remove your shoes” that was given out to expectant mothers or those with young children across the Salinas Valley. Photo courtesy of James Nolan/CHAMACOS study

As a result of the findings, the Youth Council designed a doormat bearing a message in Spanish to “wipe your feet and remove your shoes.” The mats were first distributed to CHAMACOS participants and the remainder will be given to expectant mothers or those with young children across the Salinas Valley. The group also wrote and recorded a series of Spanish radio novellas that discuss pesticide safety in the fields and at home. According to Nolan, the PSAs now air on 10 stations across California, Oregon and Washington with four of those stations airing the radio novellas around 20 times per week. Anecdotally, says Nolan, people have been impressed with the work of the youth council and groups such as the Migrant Clinicians Network are excited to share the PSAs throughout their workplace.

“The science is important,” Cardoso says. “But doing something with the science is even better.”

Beyond the Fields

While Youth-led Participatory Action Research can be an effective model for involving youth in research, these kinds of projects require additional planning and logistical work, Nolan says. At its most practical level, involving youth means budgeting or applying for additional grant funding so that everyone, regardless of age, is paid as a researcher.

On a more complex level, initiating new community partnerships can be difficult, especially when working with diverse or marginalized groups who have been historically mistreated by science. Famous examples like the Tuskegee Study in the early 1930s failed to inform African-American participants of the purpose of the study, which was about syphilis treatment, or provide adequate treatment when it became available. More recently, the misuse of Havasupai Indian DNA by geneticists at Arizona State University and the subsequent court case between the two parties highlighted how the rights of vulnerable groups can be violated when researchers fail to fully inform participants of the myriad ways their DNA could be used.

Drawing upon the muralist tradition in Latin America and inspired by public art in San Francisco and Salinas, Youth Council teens worked with José Ortiz to design and paint a 28-foot-long by 5-foot-high mobile mural (a portion of which is pictured here) as a final project. Photo courtesy of Hijos del Sol Productions and the CHAMACOS Study

Because of this, gaining the trust of a community, especially working with youth from that community, will likely always be a long-term commitment. But, if successful, it can lead to greater diversity among scientists and a more diverse range of research and perspectives.

“It’s a longer-term endeavor but it benefits people’s relationships with science,” Nolan says. “It can democratize and demystify research.”

For some in the Youth Council, the benefits have been clear.

Gallardo is now a freshman at the UC Berkeley and hopes to pursue a career in politics with a focus on environmental health. Cardoso is attending Hartnell community college in Salinas and plans to transfer to a four-year program. He hopes to help people in the community, through pesticide safety or by working as an EMT, he says, and those interests were encouraged through his work in the Youth Council. Both are still part of the CHAMACOS study that led them to the Youth Council and late last year, attended their 18th annual appointment.

As a final Youth Council project, before the group scattered across the state to begin college and work, the group decided they wanted to leave a lasting, visual legacy of their work. Drawing upon the muralist tradition in Latin America and inspired by public art in San Francisco and Salinas, the teens worked with José Ortiz to design and paint a 28-foot-long by 5-foot-high mobile mural. The mural, one of Brenda Eskenazi’s long-held goals for the project, depicts pesticide use and prevention in the fields and at home, drawing upon the findings from CHAMACOS and COSECHA. But at its heart, like the projects themselves, the mural is about multigenerational health — from mother to child to family.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!