May 19, 2020 — On a weekend in March 2019, Victoria University of Wellington microbiologist Monica Gerth stepped up to a microphone in a large white tent in Waipoua Forest, some 90 miles (140 kilometers) from the northernmost tip of New Zealand. The sun was baking the surrounding trees. A creek gently rippled across the glade. More than 50 scientists, activists, artists and Māori elders were gathered to share knowledge and inspiration on how to save an iconic tree species, kauri, from a lethal pathogen, Phytophthora agathidicida.

Elder Tohe Ashby had just finished a presentation on the kinship between the kauri and whales. Ashby had recently returned from Taranaki province, where a pod of sperm whales had been beached. In his words, they had sacrificed themselves after hearing the agony of their kauri brethren, and he had traveled there to recover their remains. Now, their bones would be ground up and used in a potion to heal the trees.

“If you believe, the power of prayers can open doors,” he said. Then he ended with a somber comment on the relation between Western and indigenous views. “Some things might gel, but I don’t think our realms can work or fit together.”

A few years earlier, Gerth would have felt far out of her depth to follow that speech. But on this day, she beamed.

“I don’t think that’s true,” she opened. “I think it’s all about finding the right people.”

Members of the Te Roroa iwi welcome participants to a four-day conference on the health of kauri, an iconic New Zealand tree. Photo courtesy of Per Liljas

Despite centuries of colonization, finding Māori culture in New Zealand takes no effort. All rugby games start with the traditional war dance haka. Māori language is mixed into everyday speech, and elements of their art are ubiquitous. However, marginalization is still a fact of the day, and cross-cultural collaboration is anything but frictionless. Spending a year reporting on Māori influence on conservation work, I found myself wading into a scene rife with conflict. Eventually, though, the conflict also struck me as a sign of vigor.

Decimated Giant

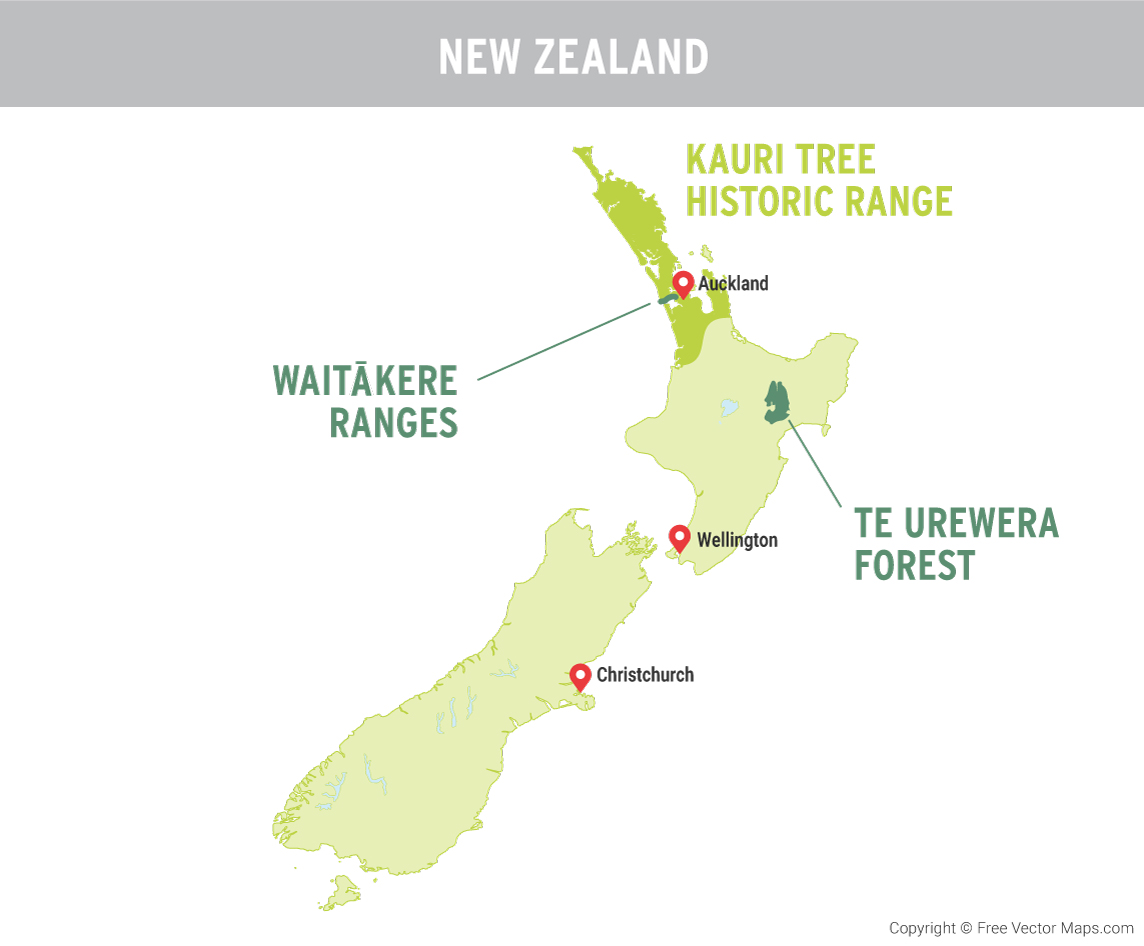

It would be fair to some extent to call kauri the redwood of New Zealand. Like its distant North American cousin, kauri is a giant conifer that can live to be over 2,000 years old. It and its ancestors dominated its habitat — about 30,000 square kilometers (12,000 square miles) across the northern tip of New Zealand — for over 100 million years, successfully coexisting with the first people of that area.

Then, in the mid-19th century, Europeans started arriving in numbers with modern tools and a price on the tree’s head. In little over a century, over 95% of the kauri forests were logged or burned. The remainders are fragmented and surrounded by pastures and monocultures. This has left them vulnerable to pests, climate change and infection by organisms carried by international trade.

Phytophthoras are particularly good travelers. These moldlike organisms can hitch rides on nursery plants or outdoor equipment, staying dormant through long voyages until, when released into soil, they are able to propel themselves toward their prey. Phytophthora was first detected in New Zealand kauri in 1972, but incorrectly identified first as P. heveae, and later P. cinnamomi, a species that has caused rampant damage on plantations and woodlands across the world, especially in neighboring Australia. In 2006, the New Zealand strand was finally recognized as a distinct species targeting kauri, and in 2015 it was named P. agathidicida, “kauri killer.”

There is no cure for phytophthora. Kauri plantations can be replaced with more resistant varieties, but that is no way to save existing forests. This is one reason New Zealand is trying a novel approach: The government and indigenous people are tackling the problem together.

Monica Gerth is familiar with both Māori and kauri. She arrived from the United States in 2007 for a postdoctoral fellowship at Massey University in Auckland on chemotaxis, the science of how cells sense and move toward chemicals. When she first heard about P. agathidicida, she figured there must be some chemical that attracts the pathogen to kauri. And if so, there might also be a way to lead it astray. Perhaps another plant could send out a “smell” that would disrupt its path. The question was where to look.

“I’m not a plant person, so I didn’t have the faintest idea where to start,” she says.

New Zealand’s largest kauri, known as Tāne Mahuta, grows in Waipoua forest. It’s estimated to be 1,250 to 2,500 years old and is more than 51 meters (160 feet) tall. Photo courtesy of Per Liljas and Te Roroa

Casual conversations opened her eyes to Māori knowledge about the local ecosystem. For example, she learned that the first step in harvesting timber is to listen for birdsong early in the morning. A particular call will mean that there are insects burrowing through a recently deceased tree. That means the tree is also ripe for harvest, as the Māori practice is to only pick dead or dying trees.

“All of that really excited Monica,” says Te Rangitākuku Kaihoro, a carver who told her the story. In turn, he says that her talk of chemotaxis interested him. “We have a similar way to describe this movement of water and proteins through root membranes. Simply put, chemotaxis are how plants talk to each other.”

Step by step, the two started getting to know each other and talking about how they might work together. Chris Pairama, another Māori knowledge-holder, joined too. It was eventually agreed that the two men would identify a number of plants that grow in proximity to healthy kauri, and Gerth would sic P. agathidicida on them in her lab to see what effect it would have. A proposal to that effect received funding from the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

“The premise of the experiment wasn’t to look at the mold or the host,” says Te Rangitākuku Kaihoro, “but at companion plants and their connection through the soil.”

Indigenous Traditions, Sustainable Management

Many scholars around the world have lifted up indigenous traditions as an exemplary way to sustainably manage forests. In New Zealand, one might think the promotion of Māori values should come naturally, since they are enshrined in an 1840 treaty between the Brits and Māori. But despite the treaty, for a long time intercultural relations were dominated by newcomers wresting land from iwi (indigenous communities). Forests were turned into pastures. Aspects of indigenous culture was banned. At the turn of the last century, New Zealand scholars suggested that both the Māori and the kauri would soon be extinct.

Over the last couple of decades, however, there has been a resurgence. The Treaty of Waitangi has gained the stature of a constitutional document. Its principles of “partnership, participation and protection” of Māori culture run through much of society. Many iwi have settled lengthy court battles and moved back home.

Waitākere Ranges, a regional park in the outskirts of Auckland, is home to threatened kauri trees as well as a magnet for outdoor adventurers. Photo courtesy of Jeff P | Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0

The struggle for the kauri is a potent testing ground for an even deeper range of influence. Most kauri stand on land over which Māori hold customary rights or for which Māori are an integral part of the management team.

Waitākere Ranges, a regional park in the outskirts of Auckland, is one such place. This forested swath of low mountains cascading into the Tasman Sea is the home or weekend destination of many outdoor enthusiasts. After almost being forced out of existence, its historic guardians, the Te Kawerau ā Maki iwi, are not as prominent.

Yet the iwi settled its differences with the Crown in 2014, and is now a treaty partner, granting it a significant say on the stewardship of the land. As the iwi’s management felt little heed was taken to the worsening kauri dieback and its connection to off-track hiking, they imposed a rāhui, cultural prohibition, against entering the woods. After a lengthy battle against authorities, and very vocal protests from hikers, this prohibition has largely started to be enforced, and offenders have been prosecuted in court.

“It’s all about being a good ancestor.” – Taoho Patuawa“We knew we’d get a lot of shit, but it was a crisis situation and nothing was happening,” says Robin Taua-Gordon of Te Kawerau ā Maki. She emphasizes that they are not looking at the well-being of this generation of Aucklanders or the next, but rather the health of the whole ecosystem. “As responsible stewards, our perspective has to be hundreds of years.”

In Waipoua Forest, home to the largest kauri, the Te Roroa iwi is managing one of the greatest tourist attractions of New Zealand’s far north. Since it regained management over the forest, it has taken the lead on the security of and accessibility to these trees, even considering largely restricting or banning visits. “It’s all about being a good ancestor,” says Taoho Patuawa, science adviser for the iwi. Another way in which Māori perspectives are actively promoted is through state funding to projects such as Gerth’s.

This has all played a part in shifting views on the environment. When the Tūhoe iwi in 2014 regained rights over Te Urewera forest, in the far east of the North Island, for example, it declared it a legal person and started assessing its health by customary means, such as the amount of awe a flock of kereru — a native forest pigeon — inspires.

New generations are starting to bring Western and indigenous knowledge together. Amanda Black, a senior lecturer in bioprotection at Lincoln University, Christchurch, is part Tūhoe. She points to the importance of younger Māori such as herself coming through the educational system while still being rooted in their culture.

“Māori get a lot of airtime superficially, which frustrates me,” she says. “A lot of environmental issues fly under the radar while people mind their daily business. But New Zealand could really lead the way. There are policies in place to bring out Māori research and unlock whatever potential,” she says.

Respect and Trust

Mixing worlds is not unproblematic. For one thing, there is the colonial baggage. Indigenous people may be less objectified these days, but Western academia still extracts and monetizes new findings.

“The threat of rape and pillage of our traditional knowledge is always there,” says Te Rangitākuku Kaihoro. On his insistence, Gerth fought her university not to claim intellectual ownership of her study. It took a good couple of months, but she succeeded.

The only way researchers know to halt a phytophthora attack is to inject a tree with phosphite, which stops the internal rot. Some iwi have refused this treatment, though, since they find it too intrusive. Then there are the different world views. For instance, the only way researchers know to halt a phytophthora attack is to inject a tree with phosphite, which stops the internal rot. Some iwi have refused this treatment, though, since they find it too intrusive.

“You have to respect that,” says Ian Horner, a plant pathologist with Plant & Food Research, a New Zealand science company, who has led a project to inject thousands of kauri. “We have to come up with solutions that make cultural sense to the people living with these trees.” Applying ground-up whale bones to the lesions of ailing kauri could even be beneficial, he says. “For all I know, the calcium could have a positive effect.”

Few elders are willing to let scientists test their methods without first earning trust. Te Rangitākuku Kaihoro thinks this guardedness sometimes goes too far, and tells of an argument in a board of elders about his collaboration with Monica Gerth.

“Two of the ladies were saying ‘don’t tell everyone everything, this is really secret stuff, we should keep it to ourselves.’” In his mind, they should let it go after the lengthy dispute he had championed against the university on intellectual property. “Sometimes we’re just too long in the tooth.”

My own experience illustrates the importance of trust, too. I met up with Te Rangitākuku Kaihoro at his home in Auckland. In the back, by his power tools, were bone pieces from that whale salvaging operation in Taranaki. He showed me pictures of a helicopter hauling the jaws and vertebrae over a cliff next to the beach.

I asked him about the healing potions, but he told me quite sternly that my presumption that he was involved with them was wrong. It was often like that during our conversations. He generously shared of his expertise and then, inadvertently, I said something he found ignorant or disrespectful, and he delivered a reprimand.

“Many people would stop talking to you if you said something like that,” he could say after a long pause. “Consider that a rap on the knuckle.”

Gerth laughs when she hears of how Te Rangitākuku Kaihoro tested me. Challenges are not necessarily a sign of distrust for Māori, but also an educational technique and a cultural feature in order to size each other up.

“I have been challenged more in this project than in any other research I’ve been involved in,” she says, “and that’s been very good.”

She describes how conferences hosted by iwi, such as the one in Waipoua Forest, put a lot of emphasis on personal relations, so it’s important to introduce oneself by describing one’s family and lineage.

“The first few times, it was very confusing and outside my comfort zone. I would typically only talk about my research at a conference, not put myself out there.” Now, she has started doing a short version of this when lecturing too. “You can see connections happening, people being more engaged and more ready to ask questions.”

Strengthened Understanding

That day in Waipoua Forest, Gerth went on to present the results of her study on the chemotaxic effect on P. agathidicida of extracts from the plants Māori elders had selected. According to traditional knowledge, forest regeneration happens in three waves, with the first one involving plants that cleanse, prepare and connect the soil for future generations of plants. Therefore, four plants that are involved in this wave in kauri forests were selected for the study.

Kānuka, one of four plants selected by Māori for study, shows promise for potentially helping kauri fight off P. agathidicida. Photo courtesy of Kathy Warburton from Wikimedia, licensed under CC BY 4.0

The effectiveness of these four plants was much higher than that of over 100 commercially available antimicrobial compounds that previously had been tested. Also, the most effective plant — kānuka, a native shrub of the myrtle family —dramatically outperformed all competition in its ability to slow down P. agathidicida’s propulsion through the soil.

“Woo-hoo,” one of the participants yelped and clapped her hands.

These are still early results produced in a laboratory. But Black is now working with Gerth, and planning to use her expertise in soil health and cultural practice to test if kānuka can be used in the wild to repel phytophthora from kauri.

Over the years it has taken to reach this point, the understanding and connections between Western and Māori advocates for kauri health have strengthened. These are slow changes, and not all are persuaded that this is the right path for Māori, Western science, New Zealand or environmental conservation. But on the scale that matters to this iconic tree and its stewards, perhaps there is time to work all that out.

UPDATED 5.21.20: Māori elders selected the plants for study.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

I am with the North Carolina Sierra Club and I will share this story with everyone I know.