Even at the building scale, HOK is using the principles of biomimicry to improve design. One pro bono design, an orphanage in earthquake-ravaged Port-au-Prince, Haiti, used lessons from the local kapok tree to provide passive cooling, collect rainwater and mimic the tree’s protective bark for shielding the building from excessive heat. With no water, sewage or electrical connections, the building’s design is heavily reliant on these sort of natural systems. “It wasn’t like an aspirational goal,” Lazarus says. “It was like we have to have a closed-loop solution.”

Lazarus says that applying the lessons of nature to urban design and architecture has such obvious benefits that there’s no reason not to.

“In a way, I don’t consider it an urban issue or not an urban issue,” she says. “It works at all scales.”

Cleansing Power

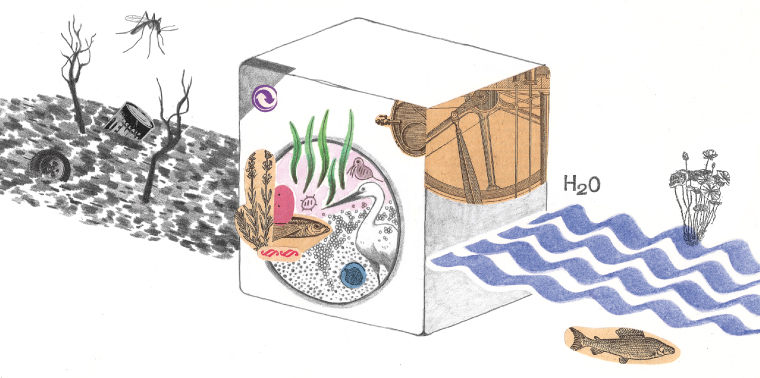

Most often, infrastructural biomimicry happens at the smaller scale and with a focus on water. One of the most prominent examples is the Eco-Machine, a trademarked water treatment technique created by John Todd and his firm John Todd Ecological Design. Based on ideas that have evolved over the last three decades, the Eco-Machine is a type of constructed wetland that mimics the cleansing power of a marshland or estuary by combining plant life, aquatic tanks and various forms of living organisms to clean wastewater through a cycle of passive processes that doesn’t require any hazardous chemicals. By traveling into and out of a series of specialized tanks filled with specific plants, fish, zooplankton and bacteria, water is refined from polluted to clean. Eco-Machines have been used at a variety of scales to process water, from the sewage of office buildings to the groundwater of contaminated sites.

Illustration by Samuel Castano

One of Todd Ecological’s latest applications of the Eco-Machine technique takes on an intimidating problem. In Grafton, Mass., the firm is working with the site of a former mill on the Blackstone River. The mill burned down in the 1990s, and a new owner is hoping to turn the site into a small village. But along with the remnants of the mill are a series of buried storage tanks that have degraded over time, leaking a heavy oil known as Bunker C into a canal leading to the nearby river.

“Our results are showing over a 90 percent reduction of petroleum hydrocarbons within the system.”

Removing the tanks and the contaminated soil would be far too expensive for the site’s owner or probably any single person. So, with a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Todd Ecological was contracted to install an advanced version of its Eco-Machine that combines a floating system of plants and a biofilter within the canal to clean and draw water up to the system of tanks on the shore. The water cycles through the various tanks, and also a series of closed cells containing special fungi that perform even more intense cleansing before returning the water to the canal.

The system began operations in June 2012. Since then, the water has shown significant improvements. “Our results are showing over a 90 percent reduction of petroleum hydrocarbons within the system,” says Camron Adibi, a project manager at the firm.

“It cost the EPA $1 million to remove oil-contaminated sediment and took six months to dredge 300 feet of the canal,” Adibi says. “The Eco-Machine cost less than half this amount.”

Heal Thyself

Though water treatment is one of the most important functions of urban infrastructure, perhaps the most visible and ubiquitous example of urban infrastructure is concrete. From sidewalks to buildings to highway dividers to bridges, concrete is what our cities are made of. Though typically thought of as a blunt tool with a limited lifespan, concrete is actually becoming better and smarter. Researchers at the University of Michigan have been developing a new type of concrete that’s modeled on the self-healing properties of biological systems. Like human skin or the bark of a tree, this new concrete is able to fill in tiny surface fractures—essentially healing itself as it degrades. By absorbing moisture from the air, microfibers in the concrete slowly expand and harden, replacing cracks in the material with the material.

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

Have read a tiny bit about bio-mimicry in the past, but nice to learn more about how it's developing in the here and now.

Thanks!

Dr. Korkmaz would be a great asset to get as a professor at a US University.

Another example of biomimetic thinking applied to urban planning is the emerging field of "urban metabolism" -- which looks at the flows of water, waste, and other nutrients through urban ecosystems. A great application of this approach is the design of Lloyd Crossing by Mithun Architects Designers + Planners, in which the design team compared flows of water, carbon, etc. against a "pre-development baseline."

My colleague Lyle Solla-Yates and I have also used this approach in our research, for instance investigating the impact of alternative waste management systems: http://www.carlsterner.com/research/2010_toward_the_green_city.shtml