October 11, 2024 —  Beyond Ireland’s rolling green hills and storied countryside, the nation’s marine territory spans more than 10 times its landmass. Its rocky, rugged coast borders a frigid, slate-hued ocean where kelp forests, seagrass meadows and cold-water coral reefs dwell beneath the water’s surface, providing habitat for an array of sea life.

Beyond Ireland’s rolling green hills and storied countryside, the nation’s marine territory spans more than 10 times its landmass. Its rocky, rugged coast borders a frigid, slate-hued ocean where kelp forests, seagrass meadows and cold-water coral reefs dwell beneath the water’s surface, providing habitat for an array of sea life.

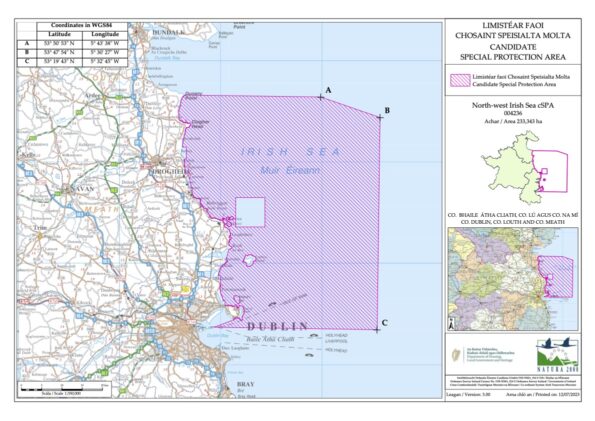

Confronted by diverse pressures, these marine ecosystems are under threat. Microplastics, industrial pollution, destructive fishing practices and rising water temperatures due to climate change, among other stressors, are contributing to the accelerating uncertainty faced by the world’s oceans, including those around Ireland. To relieve pressure on these vulnerable ecosystems, Ireland is proposing to legally designate up to 30% of its sea space as Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) by 2030 (currently that number is at 9%). It also plans to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, with offshore renewable energy (ORE) serving as a cornerstone of this effort. The country is aiming to increase ORE from a single 25 megawatt (0.025 gigawatt) offshore wind farm to 37 GW by 2050.

“Inaction to address climate change will be bad for marine biodiversity,” warns Donal Griffin, campaign coordinator at Fair Seas, a coalition of Irish environmental groups championing ocean conservation. He maintains that offshore wind farms are important to Ireland’s climate strategy but insists that environmental considerations must guide their placement. Griffin also says that placing MPAs and offshore wind farms together should be a last resort and that any protected marine space co-located with a wind farm should not contribute toward Ireland’s 30% protection goal.

Peter Coyle, executive chairman at the Marine Renewables Industry Association (MRIA), says that “the space ORE will take up will be tiny, even at a very large scale.” He assures that offshore wind farms can exist entirely outside Ireland’s 30% MPA coverage target. That said, Coyle adds, “there’s no reason why co-location can’t take place” if it doesn’t disturb the environment.

Meanwhile, as Ireland prepares to divide its waters between MPAs and ORE, the fishing industry’s role in this evolving seascape remains uncertain.

“There’s no one more concerned with making sure there’s going to be fish in the future than someone whose job relies on it,” says Edward Farrell, chief scientific and sustainability officer for the Killybegs Fishermen’s Organisation (KFO), a leading group supporting the interests of the European Union’s, and more specifically, Ireland’s, commercial fishing industry. Farrell explains that KFO members have years of experience with evidence-based marine protection. “They might not always like the result, but they accept it as long as it’s the best science.”

Still, Farrell recognizes the “spatial squeeze” from MPAs and offshore wind farms and expresses concern that Ireland’s coastal communities could be marginalized if their voices are overlooked during designation decisions.

As Ireland approaches these challenges, it raises the question: How will the government balance these diverse interests while creating an effective network of marine protection? And can other areas around the world dealing with competing interests in their own coastal waters learn anything from Ireland’s efforts and decisions?

Prioritizing Species and Habitats

For once, the Irish sun is shining, but the salty water is shockingly cold as I dive through a meadow of seagrass — a tapestry of green and red leaves swaying gently like submerged lettuce in the outgoing tide. Members of Coastwatch, part of the Fair Seas coalition, have brought me to this stretch of protected coastal waters in County Clare to demonstrate the importance of targeted habitat protection.

“MPAs should protect what is vulnerable, threatened and rare,” says Griffin of Fair Seas. “That includes pristine areas as well as those in degraded condition.”

In Ireland, this could mean protecting biodiversity-enhancing habitats such as seagrass meadows, coral reefs, sand dunes and coastal cliffs. Designations may also target areas that host endangered species of megafauna like the blue whale and basking shark or seabird breeding grounds for the Atlantic puffin and balearic shearwater. Additionally, the country’s 2022 General Scheme of Marine Protected Areas Bill includes cultural value and ecosystem-regulating services, which could include carbon storage and sequestration, as designation criteria.

A recent study from the North Sea showcases the importance of key species and habitat indicators in shaping protective strategies and co-location decisions in MPAs.

Using spatial modeling software, researchers explored how different conservation strategies would perform based on the combination of various factors, including the size of the area, the presence of sensitive habitats or endangered species, and the proximity to other protected areas and human activities like fishing and offshore wind farms. These projections can help shed light on the effectiveness of fishing regulations such as no-take zones and mixed-use restrictions, as well as the implications of co-locating offshore wind farms and MPAs.

Within the North Sea, the study found that the “spillover effect,” in which fish thriving within MPAs move outside restricted fishing zones, can lead to increased fishing pressure on the borders of protected areas. The researchers suggest this pressure can potentially diminish the effectiveness of the designation and recommend considering additional fishing regulations in areas surrounding strict protection zones.

That said, Louise Allcock, a professor of zoology at the University of Galway and current life and ocean science chair of Ireland’s MPA Advisory Group, warns that using models based on data from other areas can lead to incorrect conclusions and emphasizes the need to include local data in models. She also suggests that initial projections should serve as a starting point to guide further local research.

“Modeling the distribution of species can be extremely effective and useful for MPA designations,” Allcock says, “but your resulting data are only as good as your model input data.”

“There’s a lack of local data in a lot of places,” says the KFO’s Farrell, “but I think the fishing industry can help with that.” He envisions fishers playing a valuable role in improving the effectiveness of MPA designations. “We’re aware of sensitive areas where we don’t fish — places where reefs could damage nets or where there’s a high abundance of juveniles or specific species,” notes Farrell.

Allcock explains that managing MPAs requires consideration of the features they aim to protect. “The impact of stakeholder activities should be assessed to determine whether the activity will have a detrimental effect on the features for which the MPA was designated.” She says this philosophy should apply to all stakeholder activities, including fishing.

Marine Spatial Planning

Identifying areas for protection, however, is only one piece of the complex puzzle of ocean management. Ensuring all the parts fit together seamlessly is far from simple. Among the stakeholders I spoke with, there’s a common agreement that MPA and offshore wind farm co-location should be a last resort. The Irish government also agrees.

“We have abundant space to create protected sites while seeking to avoid impacts on economic activity,” says Richard Cronin, principal adviser for the marine environment in the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, the government body responsible for an upcoming MPA bill that will set the legal foundation for MPA expansion in Irish waters.

Still, the government must tread carefully if it intends to avoid conflict. So far, its track record is varied.

In December 2022, the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage announced the establishment of Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) in the northwest and south of Ireland. Less than two weeks later, the Department of Environment, Climate and Communications unveiled a Phase 1 map for ORE projects, moving seven proposed ORE projects into the early stages of the approval process, including an area that overlaps with a designated protected area.

“It’s smack in the middle of an MPA,” says Griffin of Fair Seas, referring to one of the proposed ORE project locations. “That’s not ideal for the MPA and not ideal for the developers.”

Emma Armshaw, marine and coastal policy officer at the Sustainable Water Network (SWAN), another member of the Fair Seas coalition, refers to the recent release of the draft Offshore Renewable Energy Development as a hopeful indicator.

“People have a lot more information now, and they want to participate with experts, as opposed to being told what to do by experts.” —Richard Cronin

“Before looking at where would be the most cost-effective to put a wind farm — where the wind is strongest, the water depth and all the technical constraints — they first identified and removed areas of high environmental impact from consideration,” says Armshaw. “I think that’s very positive, that they’re not just paying lip service to the restoration of nature and biodiversity.”

However, there is concern that the inherent value of coastal waters could be a future source of conflict. “Not all of that water can be used the same way,” says Armshaw. “It tends to be waters closer to land that are highly productive, important for biodiversity and useful for ORE.”

That’s one reason that some in the ORE industry see the transition to floating offshore wind farms as essential. “It’s the technology of the future,” says Coyle of MRIA. “We’re well past the point where this is a nice to have. It’s a must-have.”

Floating wind farm technology currently faces significant logistical challenges — notably the hurdle of anchoring heavy, buoyant turbines to the seabed, where they’re susceptible to the powerful whims of wind, waves and currents. Additionally, research raises concerns over the potential impacts of floating wind farms on deep-sea habitats. Still, the prospect of locating floating wind farms farther offshore could address MPA and wind farm overlap and reduce conflict with certain fisheries.

Stakeholder Collaboration

The town of Killybegs exists for fishing. Local lobster boats and hulking offshore trawlers crowd the docks alongside the town’s main street. Cross the road, and you’ll find fish merchants, marine technician shops and salty fishing pubs. The small village is built around Ireland’s largest fishing port with nearly every building servicing the industry in some way.Often seen as opponents to MPAs, some within Ireland’s fishing industry are embracing collaboration with environmental groups.

“Fish do come back when they’re given time,” says Tommy Flahert, a lifelong Irish fisherman, pointing to a resurgence of herring in the North Sea following a protective closure. Flaherty is one of several Irish fishers featured in a Fair Seas video series promoting the fishing industry’s role in ocean stewardship.

“When [environmental nonprofit organizations] and the fishing industry are saying the same things, it’s very difficult for the government to ignore,” says Griffin of Fair Seas, “It’s a really powerful combo.”

Stakeholder participation is touted as the key element in the Irish government’s strategy for designating MPAs and balancing diverse interests at sea.

“Building trust takes time. So, the government should start that process sooner rather than later.” —Edward Farrell

“People have a lot more information now, and they want to participate with experts, as opposed to being told what to do by experts,” explains Cronin of the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage. He points to research from Scotland and Northern Ireland referenced in the 2020 MPA advisory group report that showcase the need for local involvement in more effective MPA designations. Underscoring the pitfalls of centralized designation approaches, Cronin notes, “you get the designation, but you don’t get the buy-in.”

“I’m satisfied with the government’s track record — regardless of whether you’re talking about offshore renewables or marine protected areas,” says Coyle, noting the presence of an “elaborate consultation mechanism.”

But not everyone shares Coyle’s experience.

Farrell of the KFO expresses frustration over past difficulties ensuring the fishing industry’s voice is heard. “They all want to be a part of the process,” he says, “but they haven’t always been.” Farrell notes that in the 2023 stakeholder engagement sessions for the Pre-Legislative Scrutiny of the General Scheme of the Marine Protected Area Bill, representatives of commercial fishing and aquaculture were not included, while representatives from environmental NGOs and the ORE industry participated.

Meanwhile, Griffin points to recent marine protection designations as a contrast to the government’s strong rhetoric around stakeholder participation. “There have been quite a number of new [Special Area of Conservation] designations over the past months in Ireland, and stakeholder engagement for those has been pretty much nonexistent and very disappointing.” Though Griffin is concerned about this juxtaposition, he remains hopeful that the upcoming MPA bill will lead to stronger engagement.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!