April 20, 2020 — In the 1960s, the U.S. was enjoying an unprecedented economic expansion, and the Great Lakes region was humming with industry supplying materials to build a growing nation with well-paying union jobs and an increasingly comfortable lifestyle for a large middle class.

This story is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative. For more information, go to pulitzercenter.org/connected-coastlines-initiative. “From Rust to Resilience” is also part of Covering Climate Now, a global collaboration of more than 250 news outlets to strengthen coverage of climate change.

At the same time, the lakes themselves and many of the tributaries running into them were in tough shape, thanks in large part to the steel mills, manufacturing plants and other enterprises that had sprouted up along their banks and shores since the Industrial Revolution. Across the region, industry was dumping waste into the lakes and rivers and spewing pollution into the air with seeming impunity. The oil-slicked Cuyahoga River, which empties into Lake Erie, famously caught fire multiple times over the decades.

The 1970s brought rapid changes on the environmental front: The U.S. Congress passed the Clean Water and Clean Air acts, President Richard Nixon created the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and public awareness of environmental issues skyrocketed with the founding of Earth Day. Canada similarly adopted legislation aimed at assessing and limiting environmental pollution.

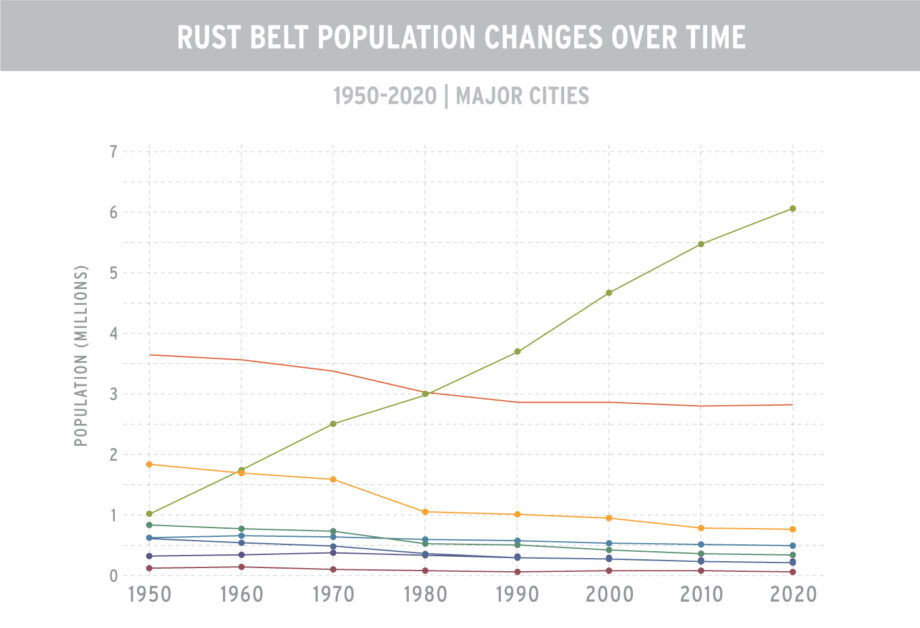

But not long after new regulations began compelling industries to clean up their act, emerging forces such as a shrinking market for steel, growth of global trade and migration of manufacturing to the Sun Belt started reshaping the Great Lakes region’s economy. Competition from foreign manufacturers caused a rapid decline in U.S. industry in the early 1980s, and cities like Gary, Detroit, Cleveland and Buffalo lost jobs and population. Buildings stood vacant, and infrastructure fell into disrepair. The region took on the name “Rust Belt,” a nod to its deteriorating physical and economic condition.

Today, the Great Lakes themselves and their tributaries are in many ways healthier. Great Lakes Fishery Commission communications director Marc Gaden, who has spent much of his life on or near the Great Lakes, says the changes over the past half century have not been unequivocally positive, “but certainly the trajectory is very encouraging. Instead of viewing the Great Lakes as a repository for pollution, we shifted to thinking of it as a source for clean water, wholesome food and recreation.”

In tandem with this ecological recovery, many Great Lakes cities and towns are enjoying an economic renaissance. And in many cases they’re leveraging their ecological assets to do so — turning once-fetid and industrial rivers and lakefronts into amenities, and building new economies based on information technology, health care, tourism and other post-industrial sectors. In 2017, Business Insider calculated that if the Great Lakes region was a country, its economy would be the third largest in the world, with education/health and trade being the largest sectors, making up a combined third of the economy.

As East Chicago, Indiana, mills smelt iron ore to make steel in the distance, beachgoers enjoy the abundant freshwater that could turn Great Lakes communities into climate oases in the decades ahead. Photo courtesy of Eric Allix Rogers from Flickr licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

However, just as Great Lakes municipalities are beginning to heal from economic shifts and traumas, they face yet another threat: climate change. From the headwaters of the St. Lawrence River in the east to the shores of Lake Superior in the west, the communities that grew up along these magnificent lakes and weathered so many transitions along the way are bracing for what could be the biggest transition of all.

Continue reading at Edge, Ensia’s multimedia platform.

Have a question about how climate change is affecting the Great Lakes region? Share it here to guide future reporting.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!