April 16, 2019 —  Detroit’s narrative over the past few decades has been grim and oft-told: auto industry abandonment, depopulation and blighted neighborhoods. But these changes have also made space for new opportunities.

Detroit’s narrative over the past few decades has been grim and oft-told: auto industry abandonment, depopulation and blighted neighborhoods. But these changes have also made space for new opportunities.

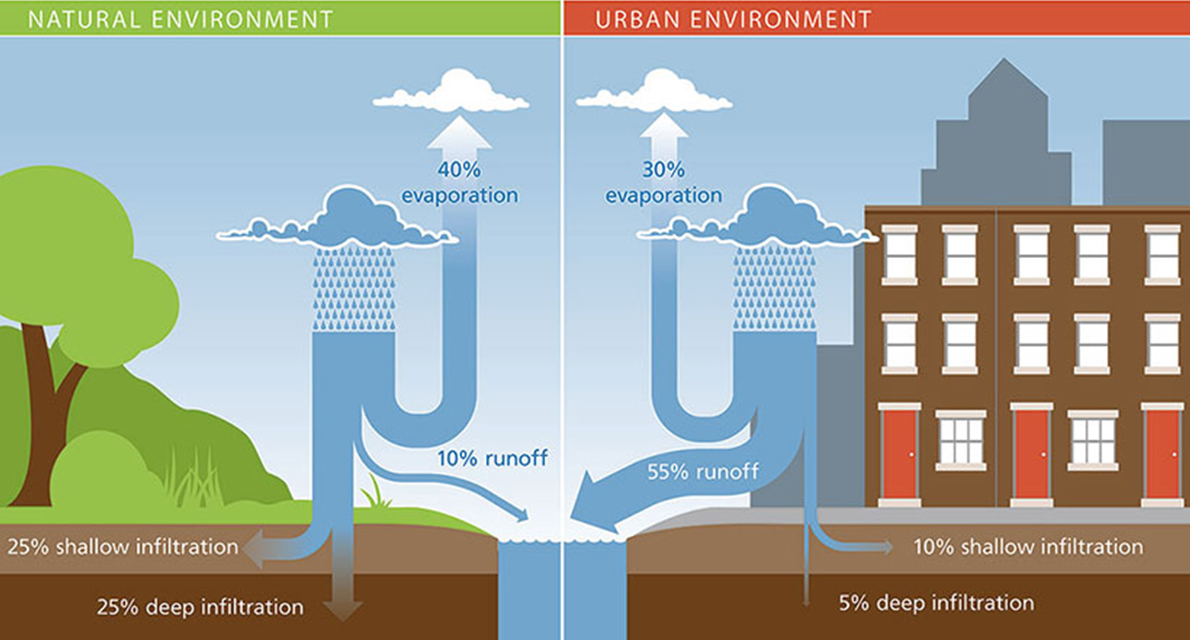

One of those opportunities is around how the city develops going forward. As with many cities around the world, as it grew Detroit followed an urban sprawl model of development, paving over grasslands and wetlands, making it so water is unable to soak into the ground. Today, that impervious development, coupled with the more intense storms brought by climate change, is making flooding a major issue for many cities. Detroit is joining a growing movement worldwide to reclaim space for water in cities and implement what is known as green stormwater infrastructure (GSI) to either absorb water where it falls or to direct it in a more controlled way to treatment plants, which today can get overwhelmed by more rushing water than they are capable of handling.

At Maheras-Gentry Memorial playground, the endpoint of a road next to the Detroit River, Khalil Ligon, senior planner at Detroit’s Planning and Development Department, explains her vision for Motor City as birds call nearby. From the city’s famous 8 Mile neighborhood to this spot, Ligon envisions a corridor of parkland and porous GSI, absorbing the floods and standing water common along the route. Her vision is shared by the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, which has built 16 GSI projects already as part of its efforts to reduce flooding and water pollution.

Green stormwater infrastructure, or GSI, helps to either absorb water where it falls or to direct it in a more controlled way to treatment facilities. Photo courtesy of City of Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, from Stormwater Management Design Manual 2018

In the same way that solar panels on people’s roofs contribute to the electricity the city needs, rain gardens, gently sloped channels covered in water-friendly plants known as bioswales, and other GSI can absorb stormwater over a large area, reducing the need to build new treatment facilities. And unlike those concrete plants, which only provide water treatment, GSI projects deliver multiple benefits, including water storage and cleaning, wildlife habitat, neighborhood beautification and recreation space, and carbon dioxide storage to help mitigate climate chaos.

Engineered Nature

The changes Detroit has experienced in recent decades have left the city with a lot of abandoned land, which makes it comparatively easy to make space for GSI. But more tightly built cities can also find a way. In fact, Detroit’s GSI program is following the lead of Philadelphia’s Green City Clean Waters, a project that began in 2011.

Like many cities in the Northeast and Great Lakes regions, Detroit and Philadelphia route stormwater runoff into the sewer for treatment. But when too much rain comes at once, the system pushes raw sewage into nearby rivers, a problem called combined sewer overflow. To deal with this problem, Philadelphia has almost 600 GSI projects, which decrease the volume of combined sewer overflows by more than 1.71 billion gallons (6.5 billion liters) annually. Bioswales along the city’s zoo parking lot collect runoff from the nearby avenue. Indian Creek, long ago buried in a sewage pipe, is once again flowing on the surface in a public park, where people and wildlife can enjoy it and where it has room to spread out when waters run high. Other cities have reclaimed routinely flooded properties along rivers to widen floodplains. And urban areas are constantly in flux. Many buildings last for just a few decades before they’re torn down and replaced. City codes can require new development to manage runoff on their sites.

But in Detroit, simply making a park where there was once a building is often not enough to prevent flooding due to its topography and geology: “The world is round, but Detroit is extremely flat,” says Palencia Mobley, chief engineer and deputy director for Detroit Water and Sewerage Department. “We don’t have a lot of elevation to move water.” Another problem is that “Detroit is full of clay soil,” says Mobley, which doesn’t readily absorb water. So many GSI projects here excavate the clay and mix it with sand or gravel so water can move underground faster. Sometimes, beneath those layers, engineers install a partially open tank that holds water for a period of time, allowing it to seep into surrounding soils. Some projects also have conduits to funnel excess water the site can’t absorb to sewage treatment pipes. All GSI projects in Detroit are engineered to manage about 2.4 inches (6.1 centimeters) of rain within a 24-hour period.

City Investment

That wouldn’t have been enough to handle the August 2014 storm that brought a 500-year flood to Detroit, but it could have taken some of the flow. Ligon grew up in the city and says she’s never seen anything like that storm. It “really inundated the entire tri-county region. Our system is just not designed to manage all of that,” she says.

At a time when water infrastructure is aging, GSI can help reduce cities’ water costs. In Detroit, with its hollowed-out tax base and recent city bankruptcy, the economic strain is particularly acute. The city has comparatively high water rates, especially for its low median income, and the water utility shut off water to 13% of households in 2016 for late payments. Contamination is also a problem: last year 57 Detroit schools tested positive for lead, copper or both.

Detroit built nine “wet weather treatment facilities” between 1993 and 2012 at a cost of US$1.5 billion, says Mobley. They don’t provide full-on sewage treatment. Instead, they perform triage on stormwater overflow: a quick settling out of solid human waste and trash and application of disinfectant before discharging it into the river. Their raison d’être is to help Detroit to comply with Clean Water Act regulations. “Having those nine facilities has allowed us to reduce [combined sewer overflow] discharges up to 95%,” says Mobley.

For that last 5%, Detroit is relying on GSI projects. The city invested US$15 million in GSI between 2013 and 2017, detaining about 40 million gallons (151 million liters) of stormwater annually. Projects included disconnecting home gutters from the sewer, instead dispersing water onto the property; removing vacant structures to create more permeable land; planting trees; and building bioswales along roadways and parking lots. The department will invest a further US$50 million by 2029, says Mobley, including six new projects this spring and summer.

Drainage Charge

The Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, like many cities’ water utilities, had long charged residents and businesses a drainage fee to pay for the wet weather facilities. But in 2016, the department changed the way it assessed the fee, and people took notice. “Everybody now is charged based on their impervious area,” says Mobley, referring to spaces that do not absorb water such as asphalt parking lots or building roofs. But business owners can earn credits against their charge — a reduction of up to 80% — by planting rain gardens or installing pervious pavement to reduce the volume of stormwater running off their property.

“Property owners who have bigger properties and pavement are reeling,” says Sarah Hayosh, who works on GSI for Detroit Future City as the local nonprofit’s director of land use and sustainability. “For the average homeowner, it might be US$15 to US$20 a month,” she says. “If you have a large industrial building or church, drainage charges might be thousands of dollars a month. It could be a breaking point for small businesses.”

Roger Skrzynski says the fee might break his business, Central Avenue Auto Parts, which has been in the same location for 90 years. He says his drainage charges are now US$8,000 per month and, in response, he has started a group called Detroit Alliance Against Rain Tax.

Other businesses support the drainage fee and are upgrading their properties to capture stormwater. Alessandra Carreon co-founded PizzaPlex restaurant in Southwest Detroit with her husband, Drew McUsic, in 2017, with goals of turning a profit but also serving the community and the environment. Because the property that holds their business is small, their drainage tax was too: just US$50 per month. But building green stormwater infrastructure fit with their values. Pizza Plex got a community grant from Detroit Future City to collect water via a grassy picnic area in the back of the restaurant. They built the project in spring 2018 — excavating soil, inserting an infiltration gallery to hold water underground and give it more time to seep away, then replacing the lawn on top. The picnic area is surrounded by vacant buildings and pavement and had been prone to flooding. But since the project was installed, Carreon says she has seen reduced flooding.

Making Water Local

GSI can work in tandem with built infrastructure to achieve municipalities’ goals around water management. But in order for GSI projects to reach their full potential, “it can’t be a bunch of sparse projects, littered about the city,” Ligon says. City managers should target problem areas where water is pooling, she says. GSI planners in other cities take it further, with a big picture plan to move flows through the watershed. So far, Detroit doesn’t have that, Ligon says, so she is part of a city council group called the Green Task Force that is championing a citywide strategy. “Hopefully we’ll see some movement toward what that looks like in the next year or two,” she says.

World population and urbanization continue to grow, spreading pavement and buildings over open land. At the same time, traditional water infrastructure like levees, river channels and dams are failing in the face of bigger storms brought by climate chaos. We are seeing the limitations of 20th century urban development and our efforts to control water. If we want fewer flooded cities in the coming years, we need to invite water in, finding it space within our human habitat.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!