June 29, 2017 — On a warm May evening in the southern German town of Stuttgart, citizen scientists gather in the basement of the city library with laptops on their desks and sparkling water by their sides. Known as “OK Lab Stuttgart,” this group meets regularly with an aim “to create useful applications for citizens using open data,” according to the website of the project’s umbrella organization Code for Germany.

This night’s discussion revolves around sensors that are helping citizens in Stuttgart and elsewhere around the world to measure air quality in their neighborhoods.

Homegrown Data

Two years ago, in one such meeting, Jan Lutz, a Stuttgart-based social entrepreneur, suggested pursuing a project that would allow citizens of his city to build easy-to-assemble sensors to measure air quality. Stuttgart has a reputation as the bad-air capital of Germany. Last year alone, particulate matter levels in the city crossed the official limit of 50 micrograms per cubic meter of PM10 — particles 10 micrometers and smaller — for 63 days, well above the European-Union-permitted 35 days.

Exposure to PM10 particles can cause or exacerbate respiratory and cardiovascular problems such as coughing, decreased lung function, asthma, chronic bronchitis and even lung cancer. The city government issues air-pollution alerts on days when the pollution is above the permissible limit, advising citizens to leave their cars at home and use public transportation.

According to a 2014 WHO report, outdoor air pollution was linked to 3.7 million deaths worldwide in 2012. The numbers are increasing each year as industrialization and vehicle emissions increase, threatening air quality in cities and rural areas alike.

Lutz’s project, called Luftdaten (German for “air data”), quickly took off because the citizen scientists thought government sensors were not sufficient for measuring air quality. The government-installed sensors in Stuttgart are placed at traffic intersections where there’s heavy traffic, and the air-quality data from these sensors represents at least the 200 square meters around the sensor. Lutz’s sensors are placed in many locations, from balconies of residential apartments to public parks, potentially providing more comprehensive data.

Der Wettbewerb ‘Wer baut den schönsten Feinstaub-Sensor?’ ist gestartet! Gesammelt wird unter #meinairrohr https://t.co/6PbAhSlrJ0 pic.twitter.com/FxylzEJmzH

— OK Lab Stuttgart (@codeforS) May 15, 2017

Inspired by the simplicity of building these sensors, the movement picked up momentum. There are now 251 of them active in and around Stuttgart.

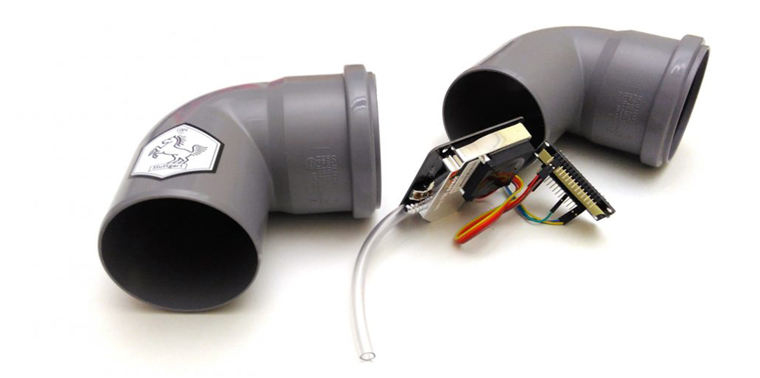

DIY Sensors Around the World

Using do-it-yourself techniques explained in a user manual that’s also been translated into several languages, including English, by citizen scientists around the world, the air pollution sensors are connected to a wireless chip, a USB power supply source and a thermometer that measures humidity in the air, which is crucial for measuring particulate matter levels. These instruments are encased in standard PVC plumbing tubes and hung from balconies at homes and at various outdoor locations. After being connected to a home’s internet, the device transmits data to the Luftdaten website and to the Luftdaten Twitter handle, which posts alerts when the PM levels exceed 200 micrograms per cubic meter. The devices cost about €35 (US$39).

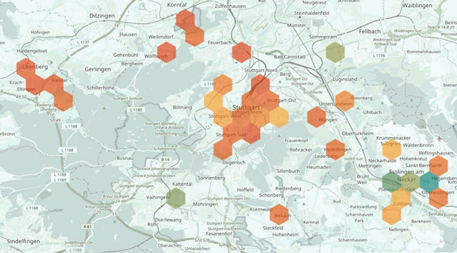

The Luftdaten website has a map with sections that indicate clean (green) and dirty (red) air. Photo Courtesy of Luftdaten

Using a map with sections that change from green (clean air) to red (dirty air), the Luftdaten website lists the concentration of particles in the air, distinguishing between larger particles (PM10) and smaller ones (PM2.5).

There are currently more than 1,000 sensors around the world with 23 countries listed on the Luftdaten website, and according to Lutz, each day the website sees 10 new sensors added. People from Malaysia to Portland, Oregon, have built them.

In March, Sascha Siekmann, a solution architect who lives in the Cully neighborhood in northeastern Portland, built one.

“Cully has some mixed-zone industrial facilities and in particular, an asphalt production facility that emits an odor,” he says. “I installed this sensor to quantify if my home and neighborhood really has an air-quality problem.” After analyzing the data, Siekmann concluded that particulate matter levels in his neighborhood don’t seem to be a problem. “My averages of PM2.5 and PM10 are well below 50, which is most likely due to my distance to major highways,” he says.

The majority of sensors — about 1,000 — are in Germany. “We wanted to provide a whole picture of the air pollution problem, not just in Stuttgart but [all of] Germany,” says Lutz.

Sebastian Müller, a sociology student at the University of Freiburg, led sensor-building sessions in Freiburg, Germany, because he wanted to bring awareness to issues related to air pollution and to provide an accurate overview of air quality in his city. There are now 20 sensors in Freiburg, thanks in part to Müller’s workshops.

The Official Response

But does the heightened awareness of air pollution translate into cleaner air? Worried by the high PM10 levels registered by their sensors, two Stuttgart residents sued the city in January. They lost their case, but public backlash followed and the city administration announced it is considering bans on vehicles on air pollution alert days starting in 2018. Currently, the city only suggests residents avoid using their cars on such days.

Ulrich Reuter, environment counselor to Stuttgart, says “all measurements can be helpful in measuring air pollution data.” However, he has reservations about the data provided by these DIY sensors. “The problem is, whether the citizens, having such a sensor, use it correctly,” he says. “One sensor may be positioned at the street, another one inside a building or in a garden. So, I’m afraid the results of the different sensors may not be comparable.”

The state agency for environment and nature conservation, LUBW, which advises the administration of Baden-Württemberg (the state to which Stuttgart is the capital), conducted efficacy tests of the sensors and raised a similar concern. “Sensors from different batches have different measurement results,” the LUBW report (translated into English) reads.

Lutz says the measurements can be unreliable, but only when the humidity is higher than 80 percent, which rarely happens in Stuttgart. “The sensors can’t seem to differentiate well between water droplets and PM10 particulates,” he says. Through firmware updates and by working out a factor to re-compute the variation of humidity, Lutz and the OK Lab Stuttgart team are hoping to address these issues.

Well-rounded Data

Lutz is aware that the PM sensors measure only one dimension of air pollution. His next citizen science project is to build nitrogen dioxide sensors, an initiative being crowdfunded now. In an industrial city like Stuttgart, NO2 emissions from automobiles are a real threat to air quality. Over and above environmental effects such as acid rain, smog and nutrient pollution, the World Health Organization, citing epidemiological studies, warns that “symptoms of bronchitis in asthmatic children increase in association with long-term exposure to NO2.”

“These sensors are a little more expensive than the PM sensors and complicated to build. But I’m confident people will have no difficulty once the initial workshops are conducted,” Lutz says. When built and installed correctly, along with the sensors that measure PM, NO2 sensors would provide a well-rounded view of air pollution, Lutz says.

According to the Luftdaten website there has been a sharp increase in installed PM sensors since the beginning of 2017, suggesting that, given the chance, everyday citizens are interested in knowing about air pollution in their cities — and potentially able to contribute to learning and doing something about it. ![]()

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

- The technology behind such sensors is still in progress, as demonstrated by scientific studies.

- Citizens may have the best intentions, but you cannot expect from them to follow the scientific method.

By definition a State has to provide security to its people. This security must include clean air. To achieve that, the State has the responsibility of monitoring its quality. Passing the responsibility of monitoring to citizens, it’s like given a gun to everybody to safeguard themselves.

In my experience working within a municipal (small city) government, one of the biggest challenges and obstacles to transformational change is the lack of engagement in citizens and voters in the issues in their community. Simply put, elected officials will not support initiatives that are not popular among the majority of voters. This leaves municipal staff such as myself with little to no leverage to suggest or implement progressive and responsible initiatives.

Citizen science is a great way to get the public involved in and aware of environmental topics and concerns in their community. Does it really matter that the data and degree of rigour of application of the scientific method is not of the same quality as that used by researchers and professionals in the field?? Or is there perhaps value in citizen science for its capacity to start conversations, engage citizens, and provide additional data (even though it may have a greater margin of error) to drive change and action where it is needed?

Scientific elitism and snobbery is a barrier to change, and I find this approach to be disappointing and frustrating.

Regards,

Edgar

Thanks

Francis