September 16, 2022 — Last year Eliza Grames had an unusual request for librarians at the University of Connecticut, where she was pursuing a Ph.D. in ecology and evolutionary biology. Grames, now a postdoc at the University of Nevada, Reno, wanted to find decades-old Russian-language articles on bird starvation as context for her dissertation research on on songbird population dynamics. What made Grames’ request uncommon is that researchers often ignore research reports published in non-English languages.

“People will just decide that they’re only going to search for articles in English,” says Grames. Over the years, English has become the default language of science. Currently, more than 95% of scientific articles are published in English, and these articles receive more attention from other scientists than do non-English papers.

“In terms of having your ideas spread or your findings acknowledged, and consequently having your credit as a scientist recognized, you must write in English,” says Constantino Macías Garcia, an ecologist at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM).

But some researchers say that ignoring non-English papers could have disastrous consequences for conservation. That’s because some researchers choose to publish their findings in their own language so that policy- and decision-makers in non-English-speaking countries can more easily find and understand them — as guidance for conservation projects, for example. A singular focus on English-language research can miss information on certain species or habitats, which in turn can affect conservation efforts. So conservation researchers are now trying to find solutions to cross the language barrier to ensure that no crucial information is missed.

Losing Biodiversity Data

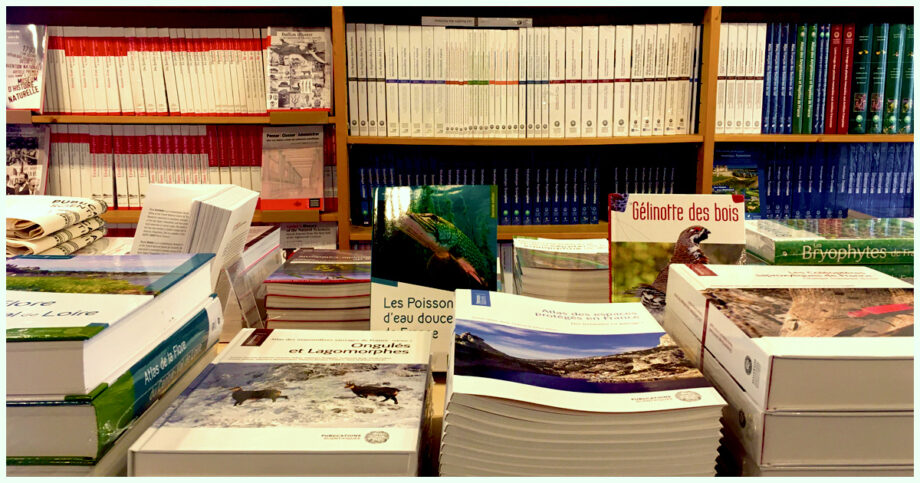

Laurence Bénichou, head of scientific publications at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN) in Paris, noticed the pattern of publishing research of value to resource managers in the vernacular in the museum’s publications. While most of the 10 journals published by the MNHN are shifting to more English-language articles, the ecology journal Naturae still publishes mostly in French. “It’s because of the target audience,” Benichou says. “Naturae is targeting managers of regional parks [in France].”

While publishing conservation research in the language of local policymakers helps conservation efforts, it can become a problem for scientists who study global patterns. For example, if researchers want to find out how animal migration has changed over time or how climate is affecting breeding sites across the world, they often analyze information from many studies. These combined analyses, also known as “systematic reviews” or “meta-analyses,” can lead researchers to new insights. But it’s difficult to gather information from papers in different languages.

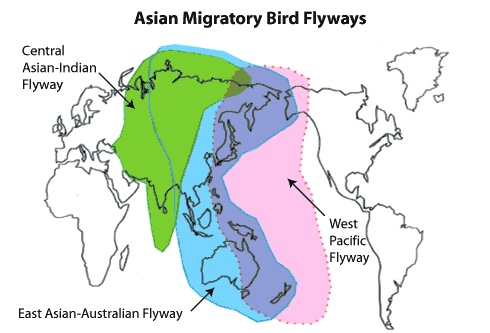

Tatsuya Amano, Australian Research Council future fellow at the University of Queensland, gives an example from his own research field: Shorebird species that migrate from Australia and New Zealand to eastern Russia fly through many countries along the way, each with their own languages. “I’m sure there are many papers published in each of these local languages on the ecology and conservation of shorebird species,” says Amano. But finding those papers and getting the relevant data is not easy.

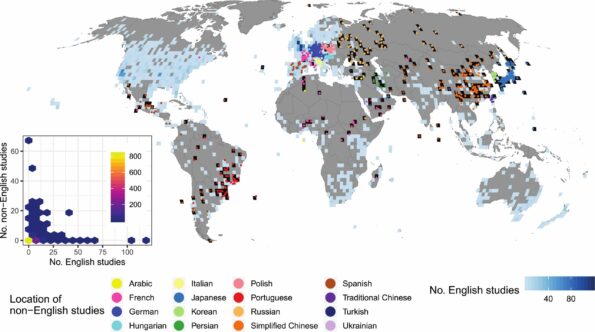

In the study, “Tapping into non-English-language science for the conservation of global biodiversity,” researchers found that crucial information could get missed if scientists ignore non-English publications. Amano T, Berdejo-Espinola V, Christie AP, Willott K, Akasaka M, Báldi A, et al. (2021) Tapping into non-English-language science for the conservation of global biodiversity. PLoS Biol 19(10): e3001296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001296. Click image to expand

Last year, Amano and his colleagues published a study in PLOS Biology revealing that crucial information could get missed if scientists ignore non-English publications. They found that including non-English research papers could greatly expand the geographical areas for which data are available, and possibly include scientific information for up to 32% more species.

Amano envisions a way to include those papers through a network of researchers translating relevant research. “I think it’s really effective to develop collaboration with native speakers of relevant languages,” he says. That’s what he did for his research study on non-English literature — he found more than 60 researchers to help identify relevant information from articles in 17 languages (including English).

Promising Options

Translation by native or fluent speakers is currently the most reliable way to get information from research papers converted to other languages. For popular languages like Spanish or Chinese, Amano says it’s relatively easy to find native speakers willing to help. But translating papers is a time-consuming task — and one that brings inequity with it: Multilingual scientists put in extra hours while monolingual English-speaking scientists are getting on with research.

But that might be changing.

One promising option is automated translation software, which is continuously getting better and easier to use. To collect crucial information from the Russian journal articles she found, Grames took advantage of a feature of the Google Translate phone app that allows a user to point a phone camera at an image of text and view the translation on screen. Even though it could only grab a few words at a time, this was easier to manage than automatic translation of the old papers, which were usually formatted in two columns with many words split between lines. “You end up with bizarre phrases,” she says. “Without being able to actually see the original side by side it’s pretty much indecipherable.”

The study of bird migration is one example of research that could benefit from access to papers in the languages of the various countries through which birds fly, but finding those papers and getting the relevant data is not easy. Image in the public domain, courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service/Alaska

Automated translation also doesn’t capture the full nuance of some of the words used in scientific papers. Grames had to ask a colleague for help when trying to understand whether a Dutch paper she found was describing a floodplain or an underground water reservoir because direct translation didn’t make that clear.

It’s also possible to get information from research publications without translating them. In Europe, where a short train ride often passes through several language regions, a new international EU-funded project, the Biodiversity Community Integrated Knowledge Library (BiCIKL), is trying to change the way biodiversity data can be accessed.

Launched in May 2021 as a collaboration among 14 research institutes, botanic gardens and other organizations, BiCIKL is building a hub of biodiversity research data that all use the same format, so they can be combined, reused and read by computers and people alike.

The MNHN is one of the institutions involved in this project, and Benichou is optimistic about the potential for using machine-readable standards for biodiversity data. “We’re trying to make sure that all the machines are able to talk to each other, and that ecologists can find anything they want, even if it’s written in Russian or Chinese.”

But BiCIKL is new, and there is still a lot of work to be done. Grames, whose work now includes developing better methods for scientists to use to build on existing knowledge, points out that there is a lot of variation in the type of data that biodiversity research collects, so it could be difficult to determine which information should be included and standardized.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

Isnt doesnt take a PhD to figure this out. If you want to be heard. Have your work translated.