November 4, 2016 — A 310-megawatt wind farm sprouting up in a remote, barren landscape near Lake Turkana in northern Kenya has the clean energy world buzzing — and for good reason.

Africa’s largest wind farm, with 365 towering turbines, is creating more than 500 stable jobs in an impoverished area where goat herding is often the only work available. It will boost Kenya’s electric grid capacity by about 15 percent, at a far lower cost than the imported oil the local utility now uses. And when it begins producing juice next year, it will signal to investors and companies that big clean energy projects like this are viable in sub-Saharan Africa.

“The impact we’re having makes me feel quite proud, frankly,” says Phylip Leferink, general manager of Lake Turkana Wind Power, who was all smiles when I met with him because the 142nd turbine had just been installed.

Megaprojects like these are deeply important for solving sub-Saharan Africa’s colossal energy access challenges at the pace governments there want. But they are not the complete answer. They are often expensive, take years to build and can’t reach everyone. In fact, the US$700 million Turkana project has been in the works for nearly a decade and the exact timeline for finishing the key 270-mile (435-kilometer) transmission line is still in question. Moreover, all of the electricity is going to southern Kenya; none will end up in the power-starved north, where high-polluting kerosene and charcoal are used for cooking meals and getting light.

So what is the best path to get electricity — preferably, modern green electricity — to the more than 1 million people in northern Kenya and 620 million people in all of sub-Saharan Africa living in the dark?

I recently spent 12 days traveling in Ghana and Kenya trying to find the answer. I was most interested in understanding the extent to which large, grid-scale renewable projects like the Turkana project can meet the region’s vast demand for power and whether more attention should be focused on off-grid renewables and other decentralized green energy efforts, which are smaller and not linked to the electric grid. The extent to which the countries can grow their economies with renewable energy — instead of costlier fossil fuels, a huge contributor to climate change — was another key question.

One thing is clear, according to government leaders and non-governmental organization experts: Plummeting costs for off-grid renewables — over 80 percent since 2010 for solar photovoltaics — are a game changer. Look no further than the remarkable rise of M-KOPA Solar, a Kenyan company that has seized on Africa’s mobile phone/mobile money phenomena (more than 90 percent of Kenyans use mobile phones and more than 70 percent are mobile money customers) to bring off-grid household solar to 425,000 customers across East Africa.

A recent study from the public-private collective Power for All, which aims to accelerate rural clean energy globally, shows these off-grid technologies can be installed in half the time and at one-tenth the cost of large utility-scale projects. Yet despite this vast potential, off-grid power is being impeded by a lack of access to capital, particularly from the World Bank and multilateral development banks, which have long been predisposed to funding big-ticket projects.

“I have no doubt, this is a millions-of-homes proposition,” M-KOPA founder and managing director Jesse Moore told a packed crowd of 500 at the recent International Off-Grid Renewable Energy Conference in Nairobi hosted by the International Renewable Energy Agency. “But we’re still very much a sideshow.”

Kenya: Leader in Renewables

Kenya is widely seen as a leader in Africa in pursuing renewables — both grid and off-grid projects — to tackle the energy access challenge. Three years ago, fewer than 30 percent of Kenyans were getting electricity from the country’s meager 2,000-MW power grid, which was powered primarily by fossil fuels. (New England’s population is less than one-third of Kenya’s, yet its grid is about 31,000 MW.) To attract power plant developers, the government adopted policies like risk-protection guarantees, standardized power purchase agreements and feed-in tariffs — all of which help ensure satisfactory payments for power that is produced. The government is especially eager to tap the country’s bountiful clean energy resources such as geothermal. A 280-MW geothermal power plant came on line in December in the Great Rift Valley, where the continent is gradually tearing apart and so providing easy access to hot water and steam below the surface, and several more geothermal projects are in the works. A new 55-MW solar plant was also announced in late September.

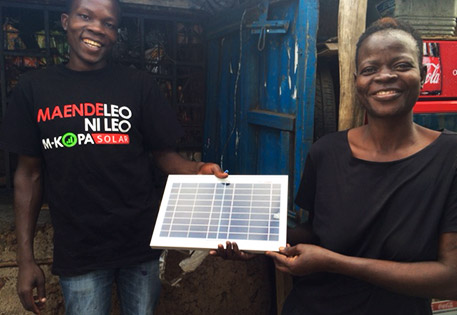

An M-KOPA sales rep talks about the company’s solar product with villagers in the Bandani neighborhood in Kisumu in western Kenya. Photo by Peyton Fleming

Government officials are pleased with the progress. “In just three years, we’ve doubled connected customers to the grid,” Kenya’s top energy secretary, Charles Keter, told the off-grid renewable energy conference audience. But he concedes Kenya will never achieve its universal energy access goal by 2020 without off-grid renewables. “In areas far from the grid, such as northern Kenya, we have to find other solutions in the near future.”

Companies like M-KOPA, Off-Grid Electric and Mobisol are already stepping in — all using pay-as-you-go business models to deliver off-grid solar services to millions of rural customers.

With a US$30 deposit and daily 50-cent payments, all via the ubiquitous M-PESA mobile money transfer system, M-KOPA’s customers get a solar panel, a couple of lights, a cellphone charger and a solar-powered radio. After a year of payments, customers own the system. Customers also develop a credit history enabling them to finance larger solar equipment that can run bigger appliances such as televisions and, M-KOPA hopes soon, small refrigerators.

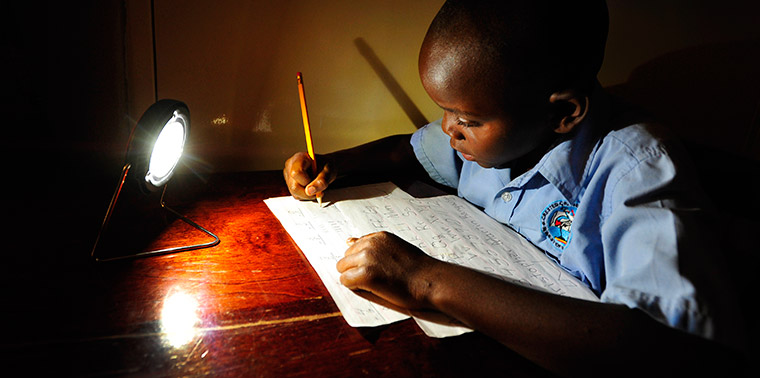

As I walked with two sales representatives through Bandani, a poor neighborhood of mud huts, dirt roads and charcoal stoves in Kisumu in western Kenya, half a dozen people ask for M-KOPA brochures. Several others were already using the service. One of those customers, Consonlata Andhiambo Odero, lives in Bandani with four children in a tiny shack and runs a shop selling charcoal, eggs and bread. Discouraged by the constant power outages, she bought an M-KOPA system a month ago. Now she has two lamps for her shop and pollution-free light so her kids can read at night. “I’m very much excited,” she says with a big smile.

Consonlata Andhiambo Odero, who lives in western Kenya and is seen here with an M-KOPA sales rep, is all smiles as she shows off new M-KOPA solar panels that are powering solar-powered lamps so her kids can read at night. Photo by Peyton Fleming

In just five years, M-KOPA has hired about 1,000 workers who are pitching and servicing customers in three East African countries. The company’s model is also being expanded to West Africa. But despite the company’s growth, a number of Africans can’t even afford the up-front costs. “The [US$30] deposit, that’s the biggest block,” said Edwin Amollo, a field sales manager for the company in Kisumu.

Ghana: Catching Up

About 4,000 miles (6,400 kilometers) to the west, Ghana is adopting many of Kenya’s strategies in expanding energy access. It lags a few years behind, especially when it comes to renewable energy. But the country is working to catch up.

Ghana’s government is expanding its electric grid with new power plants, using feed-in tariffs, competitive bidding and power purchase agreements to attract outside developers and investors. The biggest ones so far have been natural gas plants, which are being fueled by the country’s first offshore natural gas field developed last year. Solar projects are also being added to the grid, but they’re smaller — including a 20-MW solar PV project that went on line in April and a second 20-MW project awarded to a South African firm in September. Several more renewable energy projects are in the works up north, including a US$4.5 million solar installation for an agriculture venture in Yagaba Basin.

Meanwhile, off-grid solar provider PEG-Ghana launched two years ago using M-KOPA’s business model: It targets regions where people have no electricity or are dissatisfied with constant power outages, known locally as dumsors — and where mobile money is in common use.

“The reason we invested (in Ghana) was nobody was tackling West Africa at all,” said Lauren Cochran, director of private investments at the Blue Haven Initiative, a Massachusetts-based investor that helped PEG-Ghana raise US$7.5 million this year to expand its business in West Africa.

Forsaking northern Ghana — “It’s too poor,” says PEG-Ghana country manager Simone Vaccari — the company has set up 29 service centers in southern Ghana that have signed up 14,500 customers to date. Sales are growing 20 percent a month, and PEG-Ghana plans to expand to the Ivory Coast soon. “We’re in a good space,” says Vaccari, who hopes to have 100,000 customers across West Africa by 2018.

Expanding commercially viable clean energy mini-grids — small-scale, off-grid networks that supply power for individual villages or businesses — is a clear priority in Kenya and Ghana, both at the government and private sector levels.

Officials at the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Ghana office say there’s a lot of interest and potential with grid and off-grid solar, and they credit the government for setting renewable energy goals and enacting policies to encourage foreign investment. But it remains to be seen if the country can replicate Kenya’s success with renewables.

Expanding Decentralized Mini-Grids

There is another huge hole that Kenya, Ghana and other sub-Saharan Africa countries must fill to achieve their ambitious energy access and clean energy goals. While household solar systems like M-KOPA’s show promise, what about businesses, manufacturers and entire villages looking for bigger renewable systems instead of relying on a spotty or nonexistent power grid? (Due to Kenya’s unreliable grid, more than half of the country’s businesses operate their own diesel-powered generators.) And what about food suppliers who lack refrigeration due to power outages and no electricity at all?

Expanding commercially viable clean energy mini-grids — small-scale, off-grid networks that supply power for individual villages or businesses — is a clear priority in Kenya and Ghana, both at the government and private-sector levels. And, again, Kenya’s efforts are further along. This summer, the country’s president, Uhuru Kenyatta, announced plans to install 23 solar mini-grids with 9.6 MW of capacity in remote northern Kenya.

Companies such as CrossBoundary Energy are building solar mini-grids for shopping malls, safari lodges and remote hospitals. “In Kenya, 70 percent of electricity consumption is businesses,” says managing partner Matt Tilleard, who is also expanding the business to Rwanda. “That’s our niche.”

In Ghana, Black Star Energy is building solar mini-grids serving seven small communities in the country’s Ashanti region. The company’s first solar-powered mini-grid, in a cocoa farming area, launched last fall. CEO Nicole Poindexter says a key advantage of these systems is that they can run refrigerators, which are critical for solving regional food security challenges. Lack of refrigeration is a big reason why Africa loses enough food annually to feed 300 million people, according to the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization.

A Money & Policy Issue, Not a Tech Issue

For all of their early promise, off-grid renewable solutions are still in their infancy. “We have miles and miles to go. Companies like M-KOPA are doing amazing things, but their market share is still de minimus,” says Christine Eibs Singer, director of global advocacy at Power for All.

So what will it take for off-grid renewable solutions to seriously start filling the region’s energy access gap? It’s less a technology issue than a money issue.

Broadly speaking, Africa is not attracting nearly the investment dollars it needs for energy projects of all sorts. Current energy-sector investments in Africa are about US$8 billion a year; that’s less than one-sixth the US$55 billion a year that is needed to achieve universal energy access by 2030, according to a 2015 African Progress Report.

And, of the limited money that exists, very little is going to off-grid renewables, such as household solar and mini grids. From 2011 to 2014, only 11 percent of World Bank energy access funding and 1 percent of African Development Bank funding went to decentralized renewables, according to a recent Power for All report.

This funding gap was a clear sore point for participants at the Nairobi off-grid renewables conference.

“If 5 percent of that money went to our sector, you’d see millions more customers getting power far more quickly,” says Graham Smith, senior director of new markets at Off-Grid Electric, a solar start-up with over 100,000 East African customers that is relying mostly on private investment funds and venture capital to expand its business.

Power for All’s Singer says aligning government policies and key financing institutions behind more balanced grid and off-grid renewable strategies will be critical in bringing green power to Africans more quickly and at less cost.

“For overall economic growth in these countries, you’re going to need new large-scale power, but you can’t see that as the only solution,” she said. “There needs to be more deliberate and conscious integration of both centralized and decentralized solutions.” ![]()

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!