May 7, 2019 — Editor’s note: This story was the result of a reader question. If you have a question or a topic that you think needs more coverage, please email us at contact@ensia.com.

The term “resilience” is everywhere. And everywhere, it seems, it means something a little different.

Resilience has been used to describe people and systems that bounce back from negative experiences and disturbances. It has also been used to refer to systems that survive being jostled around — whether or not they go back to where they were before, or to any stable state, for that matter.

While some have argued resilience is an empty concept, the widespread use of the idea of resilience across disciplines, sectors and professions suggests it is a necessary concept. Resilience is related to change. And given the rapid change happening in the environment, technology and society, such extensive use of the term reflects this need.

It does, however, lead to some questions. Where did the idea of resilience come from, and how has it developed? More importantly, how can the concept be used in ways that help us navigate a rapidly changing planet?

Roots of Resilience

According to Ann Masten, a professor at the University of Minnesota College of Education and Human Development, the idea of resilience “emerged in ecology and psychology, or the social sciences, around the same time [the 1970s] and completely independently.” The common thread, Masten says, is that it involves interactions within and among complex systems.

Masten is a leading scholar of resilience in child development. In her book Ordinary Magic: Resilience in Development, she defines resilience as “[t]he capacity of a dynamic system to adapt successfully to disturbances that threaten system function, viability, or future development of the system.”

This definition assumes resilience is desirable. However, that is not the case in all uses of the idea.

In ecology, the idea of resilience emerged in the 1970s from the work of ecologist C.S. (Buzz) Holling, now an emeritus professor at the University of Florida. In a seminal paper, Holling described resilience as “a measure of the persistence of systems and their ability to absorb change and disturbance and still maintain the same relationships between populations or state variables.”

Lance Gunderson, a professor of environmental science at Emory University and one of Holling’s collaborators, says Holling was trying to understand how ecosystems could “flip” between different states. For example, a lake can have clear water and, given certain environmental inputs like additional nutrients, the lake can rapidly flip into a cloudy water state.

According to Gunderson, Holling used the word resilience to describe what it was about ecosystems that enabled them to fluctuate widely within a state while also avoiding moving into a different state that is also resilient. Importantly, different states can be resilient, but not desirable, like a cloudy lake. Persistent poverty is an example of a social state that is both resilient and undesirable.

Two Key Ideas

Resilience thinking has further developed in recent decades in the study of systems in which humans and nature are strongly connected (or social-ecological systems).

Lisen Schultz, acting deputy science director at the Stockholm Resilience Center at Stockholm University, describes resilience as “a capacity to persist, adapt or transform in the face of change in a way that maintains the basic identity of a system.” In the case of social-ecological resilience, she says, “we are interested in really enabling long-term human survival and well-being as part of the biosphere. … So, it’s quite closely linked to sustainability.”

Two key ideas come out of this definition of resilience. First, resilience in human and natural systems is often associated with sustainability in the face of constant change. Second, resilience involves two kinds of response to that change.

The first, adaptation, supports the resilience of a system by helping it stay in essentially the same state. However, if this state becomes untenable, the system can undergo transformational change, moving to a different stable state. So resilience is not always a matter of “bouncing back”; sometimes it involves “bouncing forward” to a new state.

Transformational change helps explain why it is important to think about scale in resilience.

“We often say resilience at one scale might require transformation at other scales,” Shultz says. “So, it could be that a farm needs to transform in order to maintain the resilience of the landscape. Or the landscape needs to transform in order to maintain the resilience of a nation.” Another example would be efforts to transition the world’s energy systems away fossil fuels with the aim to transform the global energy system to maintain the planet’s ability to adapt to climate change.

What’s common among these three meanings of resilience — rooted in psychology, ecology and the study of social-ecological systems — is the focus on change in complex systems, the interactions among different scales and resilience as a way to describe how a system handles change. The definitions differ in the what kind of system is being described as resilient and whether to define resilience as a desirable thing.

Tip of the Iceberg

While this discussion highlights some of the important threads of thinking about resilience, it’s only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the diffusion of the idea.

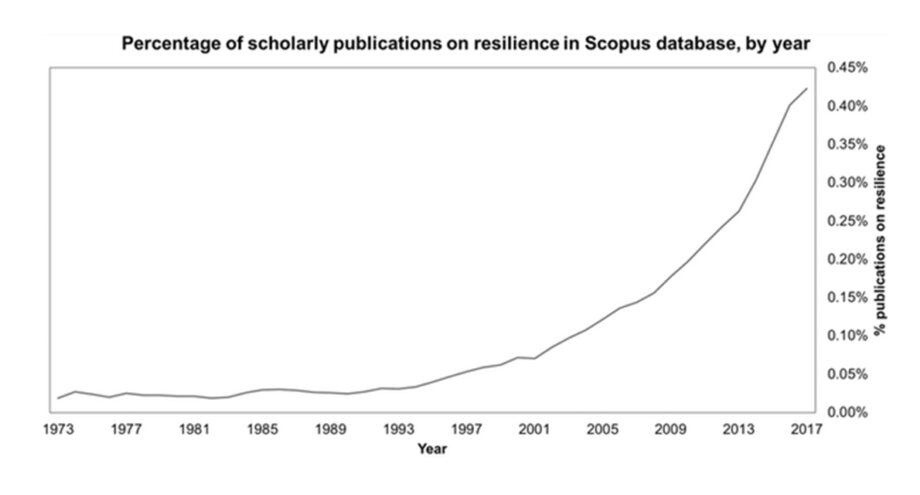

A recent paper by social scientist Susanne Moser and others that used a meta-analysis of review papers to derive seven major themes around the concept reported that a Google search of the word “resilience” yielded 67 million hits. A narrower search of only scholarly literature from 1973 (when Holling published his seminal article on resilience in ecological systems) to 2017 produced nearly 100,000 results.

The proportion of scholarly publications that address resilience has risen dramatically in recent years. Graph used with permission from Moser et al. (2019), Climatic Change, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2358-0. Click to expand.

With all this thinking, writing and work on resilience, what may really be needed is a better understanding of how the concept is being used to build a better world. As Moser and coauthors noted, “many practitioners urgently search for concrete guidance on how to build resilience.”

Resilience in Practice

In recent years, many people engaged in designing, building and stewarding the human, built and natural environment have attempted to build resilience as a way to help people thrive in the face of environmental change. Examples include “climate resilience,” which focuses on adapting and thriving in the face of a climate change, and “community resilience,” which has roots in disaster preparedness and emergency response.

“Urban resilience” is another major area of practical work around the world. In 2013, the Rockefeller Foundation launched an initiative called 100 Resilient Cities (100RC). 100RC has advanced the development of urban resilience by providing support to hire a new kind of city staff person, a chief resilience office (CRO), who leads development and implementation of a city resilience strategy.

100RC defines urban resilience as “the capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses, and systems within a city to survive, adapt, and grow no matter what kinds of chronic stresses and acute shocks they experience.” This definition of urban resilience expands the meaning of resilience by recognizing that the challenges people have to deal with don’t just come in short-term events such as a hurricane. They can also be slow-moving, as in the case of persistent inequity that frays the social fabric and leaves individuals and whole communities vulnerable.

Currently more than 50 cities around the world in the 100RC network have developed resilience strategies, and social issues have emerged as important.

“It is fascinating how [equality] is emerging more and more strongly as an outcome that resilience should achieve at a city scale,” says Braulio Eduardo Morera, director of strategy delivery at 100RC, which is scheduled to sunset later this year.

The importance of social factors, in particular social cohesion, for resilience has also emerged as important in the work of architect Doug Pierce. Pierce has helped develop RELi, a rating system and set of standards for building resilience from building to community scales.

“Even if you have a building, neighborhood or infrastructure that can weather some kind of extreme event, if you don’t have cohesiveness within the population that is part of that, it’s hard for them to respond to the event while it’s happening,” Pierce says. “And they can’t rebuild afterward if they are not cohesive.”

A Path Forward

As practitioners work on building resilience, efforts to ground the concept in specific places and systems is helping contribute to the development of a shared understanding of resilience that enables positive action.

“People respond really well to highly tangible little case studies,” Pierce says.

Masten, for her part, says that discussing specific scenarios helped an interdisciplinary group of scholars she was part of develop a shared understanding of the concept. And, with respect to city resilience strategies, Morera describes “clarity about shocks and stresses” as an essential part of building urban resilience effectively.

More generally, social scientists recommend asking clarifying questions that ground resilience in specific systems and relationships — questions like, “Resilience of what?” and “Resilience for whom?”

For example, a city could ask which climate threats — things like more intense rainstorms or heat waves — it wants to make a priority when focusing resilience planning. Within these priorities, the city can then ask who should be a priority — and could consider groups like residents of low-income neighborhoods, members of certain cultural groups, children or elderly people.

Answering questions like these can be a challenge. But given the state of the planet, resilience will likely continue to be called upon to provide a framework for working across sectors and disciplines to grapple with all kinds of change.

Reflecting on the widespread use of the concepts of resilience, Masten says, “I think it’s because we are as a planet faced with major threats that are challenging multiple systems simultaneously. And if we’re going to respond effectively, whether its climate crisis, terror attacks, pandemics or whatever, we have to be able to integrate what we know.”

Editor’s note: Kate Knuth previously served as chief resilience officer for the City of Minneapolis, a position funded by 100 Resilient Cities.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!