August 20, 2020 — Lately, you may have heard someone say that we have reached a “tipping point.” This year alone, with the economic downturn caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and the sustained civil unrest sparked by the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, we have witnessed dramatic shifts in our social and economic states of being.

These events may even have resulted in you or someone you know reaching a personal tipping point, such as the loss of a job or a large rift in a family regarding social perspectives. Big or small, these shifts — spurred by disruptions — indicate that in some way a point between the way things were in the past and the way they’ll be in the future has been met and passed.

A wildfire is a classic example of a tipping point that moves a system into a new state of being. Photo by Kari Greer/USFS Gila National Forest (Flickr/Creative Commons).

Ecosystems are also subject to disturbances and major shifts. A wildfire clears a forest, creating conditions for new tree species. Agricultural runoff pollutes local waters, depleting the oxygen fish need to thrive.

Sometimes the change that is taking place is relatively small and reversible. But sometimes the change is large and extremely difficult, if not impossible, to reverse. It’s as though the entire system has taken a plunge over the edge of a precipice to a new place. That, in essence, is what a tipping point is.

Being aware of when systems are headed toward this kind of change is the first step to being able to avoid undesirable plunges, encourage desirable ones or nudge systems that are in an undesirable state toward a desirable one.

Visualizing Tipping Points

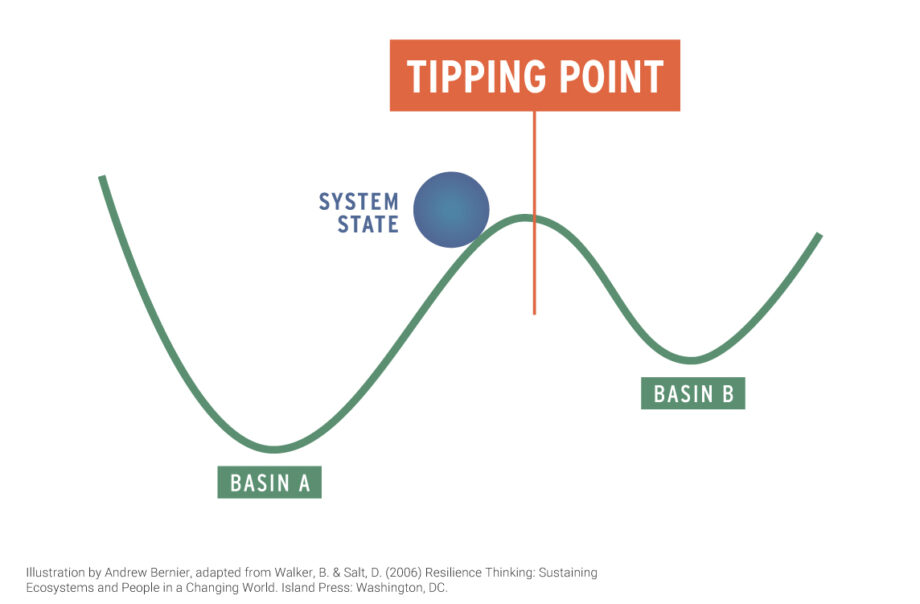

In Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World, Brian Walker, a resilience researcher with Australian National University and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Organisation, and science writer David Salt offer a mental picture to help visualize a tipping point: They describe a system’s state of being as a ball rolling around in a basin where the depth and diameter is constantly changing and the ball is adjusting its movements accordingly.

The basin is a regime, a set of patterns and occurrences. The edge of the basin is the tipping point — the point at which the ball can leave the basin entirely and enters an entirely new state. The deeper and wider the basin, the more likely the ball will stay in it, even though it’s in constant motion.

A basin’s width and depth are always changing due to variables such as events (such as demonstrations), levels of something (such as greenhouse gases in the atmosphere) or public sentiment (such as attitudes toward wearing masks). These variables interact with feedback loops, in which the effects of a change in a system themselves affect the system.

In this illustration, the ball is the current state of the system. Basin A is deeper and wider than Basin B, suggesting a more resilient regime. If the system is sufficiently disrupted, the ball may pass the Tipping Point into a new regime depicted by Basin B. Note that because Basin B is shallower and more narrow than Basin A, the ball will more easily escape it to return to Basin A or move onto another regime.

Feedback loops come in two types. Balancing feedback loops help temper the rate of change in a system. Reinforcing feedback loops speed up the change. If reinforcing loops outweigh balancing loops, the system may flip over the edge of the basin and into a new regime.

Planetary Points

In 2009, Johan Rockström, executive director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University, and colleagues introduced nine “planetary boundaries” — identifying what they call the “safe operating space for humanity” in areas of climate change, biogeochemical nitrogen and stratospheric ozone, among other critical ecological systems humans depend on. The team assigned specific boundaries for seven of these.

Originally they wrote that we had passed three of them (nitrogen biochemical flows, biodiversity loss and climate change) and were approaching others at an increasing pace. In a 2015 update, they included land-system change and phosphorus biochemical flows boundaries among those being passed. While they don’t say we’ve gone over any tipping points, exceeding these boundaries weakens balancing feedback loops and could indicate that the system is headed toward the edge of the basin.

Although we may not have actually passed tipping points, planetary boundaries defined by researchers at the Stockholm Resilience Centre suggest we could be headed in that direction for biodiversity loss, nitrogen flows, phosphorus flows, land system change and climate change. Photo courtesy of the Stockholm Resilience Centre. Click to expand.

Focusing on climate change, there is some temperature at which ecosystems reach tipping points. Estimates of what that is change as scientists collect more data. Last year in the scientific journal Nature, Timothy Lenton, director of the Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter and colleagues provided evidence that myriad ecological systems will undergo regime shifts if planetary warming exceeds the tipping point of 1.5 °C (2.7 °F). This number is lower than goals set to limit warming at 2 °C and current projections of 3 °C.

“In our view, the evidence from tipping points alone suggests that we are in a state of planetary emergency: both the risk and urgency of the situation are acute,” they wrote. Although acquiescing that we already may be past the point of no return on climate-related regime changes, they observe the reinforcing feedback loops can still be slowed, reducing planetary harm. They call for international action, noting that “the rate at which damage accumulates from tipping — and hence the risk posed — could still be under our control to some extent.”

Why Think About Tipping Points?

Thinking in terms of tipping points is a worthy endeavor because it provides a clear picture of variables and risks that decision makers can use to craft policies.

To start, decision makers need to decide whether we should stay in a particular situation or flip the system into a new basin and adopt a new regime. In the case of climate change, wanting things to stay the same would involve heeding identified greenhouse gas thresholds.

Once that decision is made, the next step is to figure out how to achieve the goal set in the first step. As policy makers debate how to mitigate climate change, options include reducing reinforcing feedback loops (for example, by reducing the amount of greenhouse gas emissions produced) or increasing balancing feedback loops (for example, by reducing deforestation and actively restoring carbon sinks).

With limited resources to do both, Donella Meadows, in her landmark work Thinking in Systems, says the more effective decision is to reduce reinforcing feedback loops before increasing balancing feedback loops.

Lenton and his colleagues, for their part, suggested that it might be possible to avoid the regime shifts they describe by stabilizing the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere within 30 years. At the same time, they admitted that there’s a chance we may have already gone over the edge.

One example of wanting to flip to a new regime is currently unfolding, as seen in the global protests in response to police killing unarmed black people. It could be said the killing of George Floyd was the tipping point, though his killing is one of many in a long succession.

Protests in the wake of the killing of George Floyd suggest we may be on the brink of entering a new regime of racial equality. Photo courtesy of Fibonacci Blue from Wikimedia, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Right now we appear to be in the cascading effects of entering a new regime, be it protests, social media discord or city council resolutions regarding police funding. Crafting law and policies that foster social justice, along with reforms to police budgeting, would keep the system in this new regime of racial equality. If not enacted, the system can flip back to the old regime.

Once we cross a tipping point, the new basin may be too large to escape. And even if we want to go back, the original basin may now be so altered that the regime we once knew, with its familiar patterns and behaviors, is no more.

In the age of Covid-19 and talk about when things will go back to “normal,” those who argue we cannot go back to what once was for various reasons — be it ecological harm, economic inequality and/or social injustice — may be right simply because what was normal may no longer exist. Time will tell what visiting restaurants, salons and movie theaters will be like a year from now — but there’s good chance it won’t be like a year ago.

A forest may regrow in the wake of a fire, but it’s not the same forest it was before. Photo courtesy of Timo Newton-Syms from Flickr, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Ecologically, we see this when a forest recovers after a fire. Vegetation returns, but it’s mostly new tree species better suited for damaged soil.

Similarly, as our planet warms, efforts to return to the world we knew before climate change may be beyond our capacity. To the extent this is the case, our job becomes, not avoiding change — which may be impossible — but figuring out and adapting to the new circumstances.

Editor’s note: In line with Ensia’s ethics statement, we disclose that Ensia editor in chief Mary Hoff met Andrew Bernier while she was a journalism fellow at Arizona State University.

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!