March 11, 2013 — Land provides us with resources aplenty. We grow crops for food and fuel in its soil, extract metals from its rocks, raise livestock on its surface and drill for oil beneath. But as demand for these resources grows, humans are looking to the ocean to meet many of the same needs: pulling metals from the seafloor, farming and harvesting fish, growing algae for fuel and food, drilling for oil in ever-more-remote locations, seeking novel natural products, and harvesting wind or wave energy offshore. On land these activities often have degraded our environment and forced regulations to play catch-up. As our sights move to the sea, might there be a chance to do things right earlier?

“We have 3 billion people on the planet who are working to become middle class. The reality is that in order to do that, where are the resources going to come from?” asks Simon Reddy, executive secretary of the newly formed Global Ocean Commission, an independent body of political leaders, business leaders and development specialists. “It’s clear that the high seas is going to play a major role in the future as the technology develops to be able to exploit them.”

For some resources, the sea may offer opportunities with fewer impacts than on land, as long as we proceed with care.

Make no mistake, all too much damage has occurred already. Many wild fisheries are devastated, some irreversibly. Lack of regulation of the high seas has led to an estimated 11 to 26 million metric tons of illegal and underreported fish caught each year. The Deepwater Horizon disaster showed that offshore oil wells pose huge environmental risks — risks that could be even greater if thawing Arctic seas allow increased drilling in that region, where cold waters could hamper cleanup.

But for some resources, the sea may offer opportunities with fewer impacts than on land, as long as we proceed with care.

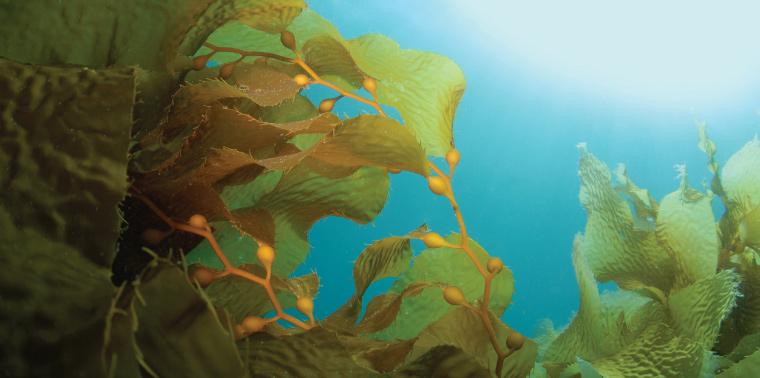

Seaweed biofuels, for example, could skirt the competition for land between food and fuel crops, and seaweed does not have the difficult-to-digest lignin that makes woody land plants tough to convert into fuels. As a result, some are looking to expand the ancient industry of seaweed cultivation. While fuel applications are still a ways off — Pål Bakken, CEO of Seaweed Energy Solutions based in Trondheim, Norway, projects large-scale fuel production by 2020 — production of higher value chemicals such as bioplastic components or growing seaweed to soak up excess nutrients from contaminated waters could come sooner. In one scenario, rigs for growing seaweed would be placed in areas of high nutrient concentration, whether from aquaculture or agricultural runoff. The seaweed would consume the nutrients and could then be used for fish feed, to make specialty chemicals or for biofuels. Bakken’s company is developing rigs that can grow seaweed offshore, hatcheries, and breeding programs to select the optimal strains for fuel production.

Deep sea mining — specifically the harvesting of copper, gold, silver and more from the sulfide deposits that comprise the towers and chimneys made by deep-sea hydrothermal vents along mid-ocean ridges — has the potential to be a success story. “I wouldn’t have any prejudgments as to whether it’s better or worse” than land mining, says Alex Rogers of the University of Oxford, UK. “If these resources are required, they’ve got to be taken from somewhere, [and] if we’ve got to extract them from somewhere, what’s the least harmful way of doing this?”

Mining deposits at or near the seabed surface using robotic machinery could be less destructive than land-based mining. On the other hand, hydrothermal vents are unique ecosystems that would be damaged by the mining. Several researchers commend one leading company, Nautilus Minerals, for its apparent intention to mine with care, leaving areas untouched that could repopulate the region with endemic larvae.

“If we can get it right to begin with, wouldn’t that be amazing?” — Cindy Lee Van Dover

“On the international scene, it’s very much an opportunity to try to work with industry to make sure that best practices are used,” says Cindy Lee Van Dover, a deep-sea oceanographer and director of the Duke University Marine Laboratory. “If we can get it right to begin with, wouldn’t that be amazing?”

As natural resource development turns to oceans, regulation and enforcement become big concerns. Many activities aimed at harvesting the oceans’ resources will happen in waters that fall under the control of particular nations. But beyond these boundaries lie the high seas.

While there is opportunity to be proactive in regulating how we tap the oceans, when profit is involved there is reason to be wary, notes Maurice Tivey, a geophysicist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Although the International Seabed Authority, an organization established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to regulate the seabed outside of national waters, has established regulations only permitting exploration at this point, Tivey says enforcement is difficult. “Exactly how companies or countries are going to abide by these rules, who knows? You’re out in the middle of nowhere and nobody else is out there for weeks, months, years on end.”

The Global Ocean Commission was set up to tackle the problems of overfishing, habitat and biodiversity loss and governance of the high seas. When the U.N. Law of the Sea was signed in 1982, Reddy says, “I don’t think it expected technology and demand to increase so rapidly. We now have the ability to go much deeper and much further into our oceans.” Over the next year or so, the commission will come up with a short list of recommendations for managing areas beyond national waters — some 45 percent of the planet’s surface. The group plans to release its findings in early 2014 ahead of the U.N. General Assembly’s planned discussions on protecting high seas biodiversity.

“All too often we make policy measures once the horse has bolted, so to speak,” Reddy says. “I hope that this is an opportunity to get the policy measures and the governance in place, so that our use of the high seas is effective and efficient from the get-go.”

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!