January 10, 2013 — Since he founded Solar Works in 1986, John Parry has focused on a lot more than profits. Through the Sebastopol, Calif.–based business, which installs solar energy systems in residential and commercial buildings, Parry aims to help address what he sees as an urgent environmental emergency facing the planet. “From my point of view we are in a major crisis here on Earth, and taking action is necessary if we want to have any chance of surviving,” says Parry.

So last year, when Parry heard from a friend and colleague about a new corporate form recently passed into law in California, he immediately knew it was a structure he needed to adopt. Called the benefit corporation, it targeted companies just like Parry’s—for-profit firms that consider environmental and social missions as important as their money-making goals. Commonly known as B corporations, businesses incorporated under this structure are required to consider how their decisions affect not just shareholders, but the environment, society and employees as well.

Solar Works founder and president John Parry (left, with spouse and Solar Works vice president Laura Goldman) jumped on board the B corporation bandwagon the day California began accepting applications. Photo courtesy of Solar Works.

In early January, Parry found himself at the office of California’s secretary of state, near the head of a line of 40 like-minded companies waiting to hand in their documents and become B corporations. “This is a corporate structure completely aligned with my way of thinking,” he says.

Solar Works is typical of more than 120 businesses that have signed on to become B corporations over the past year and a half or so in the 11 states that have adopted such legislation. The companies range from well-established household names like Patagonia to fledgling start-ups. They function as a type of hybrid—for-profit businesses with altruistic missions at their core.

Bottom-Line Bind

The desire to do good while doing well is not an unheard-of trait among businesses: Perhaps 50,000 enterprises with that goal exist in the U.S. today, according to B Lab, the Berwyn, Pa., nonprofit that has been the prime force encouraging states to adopt B corporation legislation.

However, their ability to do so has been hindered by a legal stumbling block. Traditional corporations must, by law, consider first and foremost the financial interests of shareholders. Profit, in other words, before anything else.

That leaves triple-bottom-line companies, as they’re called, in a bind. If they want to take an action that helps achieve their environmental mission—say, buy from a supplier with a low carbon footprint—it could hurt their profits. The vendor, after all, might charge higher prices than a less environmentally friendly competitor. But if they were to choose that less profitable path, it would mean they had violated their fiduciary responsibilities to their shareholders. At the same time, it’s hard for investors and consumers to tell whether a company that claims to be triple bottom line is the real thing.

B corporation legislation aims to address that quandary by baking into articles of incorporation some important requirements. Companies have to create what’s called a “general purpose benefit,” defined as a “material positive impact on society and the environment.” In most states, B corporation directors must consider the effects of their activities on employees, customers, the community and the environment in addition to shareholders. And if the corporation takes an action that can harm its mission, shareholders can sue to hold the business accountable. In addition, to prove their bona fides, companies have to produce an annual report detailing their social and environmental performance using a third-party standard. “Our belief is the strongest protection for these companies is to have a statute ensuring their right to consider things other than maximizing profit,” says Erik Trojian, director of policy at B Lab.

Definite Draw

Most company owners, like Parry, seek to become B corporations to align their corporate structure with their principles. But there’s also a financial motivation—the belief that the seal of approval will help them raise money from impact investors interested in financing businesses that are trying to create substantive societal change. According to some studies, there’s as much as $3 trillion worldwide in such money available. In addition, because a B corporation’s triple-bottom-line mission is protected by law, investors would have to respect those priorities later on.

Gary Gerber, CEO and co-founder of Berkeley, Calif.–based Sun Light & Power, which does solar power installations, registered to be a B corporation in January. He says he’s seen the competition heat up significantly over the past two years or so as more venture capital–backed players have entered the market. To compete, he figures he needs to raise outside money. But he doesn’t want to do business with investors who might want him to make compromises in areas such as quality of service or benefits for his 70 employees. That’s one reason why he jumped at the chance to become a B corporation. “There’s the possibility now of finding money to help us grow while protecting the triple-bottom-line nature of the business.” he says.

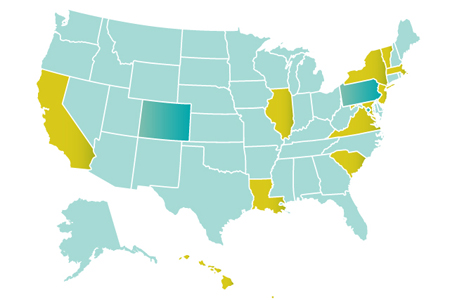

STATE-BY-STATE As of this writing, 11 states—California, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, South Carolina, Vermont and Virginia—have passed legislation enabling businesses to incorporate as benefit corporations. Colorado, Pennsylvania and Washington, D.C., are among those formally considering such legislation. To learn more, go to ensia.us/bcorpstates.

Or take Pennye Jones-Napier, whose company in 2010 became the first in Maryland—and in the nation—to incorporate as a B corporation. Jones-Napier and her partner run The Big Bad Woof, a franchise and store that sells eco-friendly pet food and supplies. They also hold regular events for the community—for example, showing films such as “Fresh,” a documentary about the local food movement, and “A Chemical Reaction,” about a community in Canada that worked to ban the use of pesticides for lawn care.

“Becoming a B [corporation] fit us like a glove,” she says. “It was an appropriate way to formally state we’re concerned with people, planet and profit.”

But, like Gerber, Jones-Napier also signed on as a B corporation to help the company raise money. By registering under the new corporate form, she was able to attract several like-minded investors who were impressed by the move and provided low-cost loans. “I would say we would not have been able to open the store were it not for angels who said they believed in what we were doing,” she says.

For Jones-Napier, there’s also been a marketing benefit. The Big Bad Woof’s website touts the company’s standing as the first registered B corporation in Maryland, and she and her partner tend to talk it up with customers. They also speak frequently at events in the area about the corporate form. While she can’t say whether customers patronize her store because of the B corporation status, she has found they often bring the topic up in conversation. What’s more, it has been a definite draw for prospective employees “who want to work for a company that believes in following the three Ps,” she says.

The B corporations structure fits her pet supply company’s business philosophy “like a glove,” says Big Bad Woof co-owner Pennye Jones-Napier, shown here at the company’s Hyattsville, Md., store. Photo courtesy of the Big Bad Woof.

Way to Go

Still, the new structure has a way to go before it becomes standard operating procedure. “A lot of firms just don’t know about it,” says Andrea Chen, executive director of Propeller: A Force for Social Innovation, a startup incubator in New Orleans that helped several fledgling companies become B corporations when the Louisiana law went into effect in August. She’s held three workshops recently for companies interested in finding out about the law, featuring lawyers who discussed the legislation. The most recent one attracted about 40 attendees.

Then there’s the LLC problem. Many triple-bottom-line companies are privately held limited liability companies (LLCs). Registering as a B corporation requires them to incorporate—a change that can have tax implications for company partners under certain circumstances. That’s why Maryland created a benefit LLC designation in 2011.

But proponents of the legislation say it’s only a matter of time before a critical mass of states adopt the statute—and triple-bottom-line companies register by droves. It’s been not even two years since the first state adopted the legislation, they point out.

Says Stefan Doering, managing partner of Shift Group, a New York City–based training firm for triple-bottom-line companies and a consultant specializing in that area, “This will help lend further legitimacy to the triple-bottom-line movement, help attract more investment and boost the development of more social enterprises.”

Beyond B

The benefit corporation isn’t the only option for mission-driven for-profit companies. The following two choices are also possibilities:

L3Cs. Nine states and two Native American tribes recognize this form, which is more formally known as a low-profit limited liability company. There are about 600 such businesses, which must have a charitable or educational purpose. L3Cs were created to be treated as program-related investments. In the U.S., foundations are legally obligated to devote 5 percent of their assets every year to charitable purposes. They can do that through a PRI as long as the organization has a charitable or educational goal as its primary objective. The jury is still out, however, as to whether many foundations will be willing to treat L3Cs as a PRI investment.

Flexible Purpose Corporations. Companies that adopt this corporate form, which has been passed only in California, don’t have to meet general public benefits. Instead, the law allows these corporations to include in their bylaws one or more “special purpose” activities, which may (but does not have to) include charitable and public-purpose activities. The structure protects directors from claims that they violated their fiduciary duties by considering nonfinancial goals. While they don’t have to produce annual assessments based on third-party standards, these corporations are required to deliver annual reports that include a discussion of their special purpose activities.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2012 issue of Momentum magazine, Ensia’s predecessor, as “B is for Better.”

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!