February 15, 2018 — Driving down U.S. 20 toward Cleveland, Cullen Naumoff knew something had to change.

Naumoff, director of sustainable enterprise for the Oberlin Project in Oberlin, Ohio, had recently launched a food hub with colleague Heather Adelman. Food hubs bring together what small farmers produce into quantities needed by big buyers like schools, restaurants and supermarkets. The problem? The Oberlin Food Hub was so successful that demand was outstripping the ability of participating farmers to meet it. Naumoff turned to other regional food hubs — and soon found herself driving all around the region to pick up and deliver lone bushels of produce — encumbering the expenses of big food companies without benefiting from the economies of scale they enjoy.

“All we had done with the food hub was shrink their model,” she says, “so local produce would never be able to compete.”

Then Naumoff met Ohio State University entomologist Casey Hoy at a food conference. She told Hoy of her frustration trying to incorporate a higher level of complexity into her food hub enterprise.

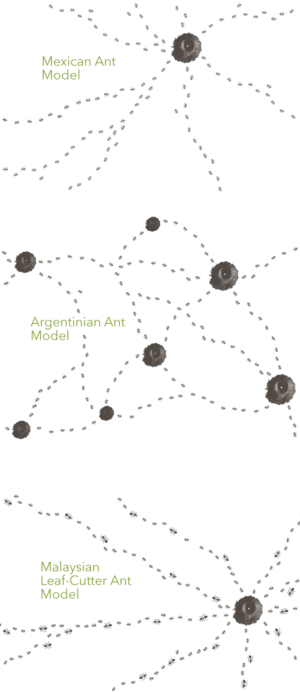

Stylized versions of three ant foraging patterns offer insights into strategies for boosting efficiency of a growing sustainable food system. Illustration by Sean Quinn

“Insects are so diverse they have probably already solved it,” Hoy responded. He then shared what he had learned from ants about efficient transportation.

Ant colony optimization is an approach to applying ant behavior to solving engineering and operations problems. Different ant species, Hoy said, use different kinds of networks of nests and paths in between them to optimize food transportation. In the process, they create a library of strategies humans can tap to solve our own food transportation challenges.

Mexican ants, for example, use a hub-and-spoke model like big food distributors, with a central nest and ants that make trips fanning to and from the center as they search for food. Argentinian ants, rather than using permanent nests, are constantly on the move, splitting and joining in new groups and nesting temporarily as they go. Malaysian leaf-cutter ants create central nests, but the ants are different sizes and carry different loads to match — with small ants, for example, carrying small leaf-cuttings and larger ants carrying bigger ones.

Hoy’s insights provided Naumoff with new ideas for meeting her food transportation challenge. She began moving her food transportation strategy from the Mexican ant model toward the Argentinian ant model Hoy described.

The resulting network, called Farm Fare, uses information technology to display food available from participating food hubs online. The various hubs can use this information to purchase needed foods in bulk and locally from the region. For example, if a buyer needs more red carrots than its own hub can provide, it can see — and purchase — red carrots available from other hubs in the network.

The Oberlin Food Hub is working to distribute locally produced food to major buyers as efficiently as possible. Photo courtesy of Oberlin Food Hub and partners.

Naumoff is now exploring a new model inspired by the Malaysian ants’ approach. Her thought is to offer local truck fleet owners the opportunity to take on food hub orders when returning empty from other jobs. Essentially, the various truck drivers would be the equivalent of different-size ants transporting different-size loads among hubs.

“It is a win-win-win,” Naumoff says. “Good for the local fleet owners who make extra money on a run they have to do anyway, good for local food that does not have to make multiple trips to finish an order, and good for the environment because trucks are always full and traveling short distances so emission levels are lower than conventional agricultural systems.”

“I am using the economies of cooperation to compete with the economies of scale.” – Cullen NaumoffAdopting the ant-inspired distribution strategy has helped Naumoff move closer to her goal of paying small farmers a reliable living wage and meeting the food needs of wholesale customers while competing with the large food distributers. “I am using the economies of cooperation to compete with the economies of scale,” she says.

Naumoff and others working to create more sustainable food systems face many other challenges, such as degraded soil, loss of food knowledge, poor nutrition, poverty, obesity, hunger and food access, just to name a few.

As Naumoff looks with satisfaction on the food system distribution solutions ants have inspired, one can’t help but wonder: What other problems does society have that nature has already solved? ![]()

Editor’s note: Liv Scott produced this feature as a participant in the Ensia Mentor Program. The mentor for the project was Sarah Gilman.

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

are there any suggestions to our economists ?