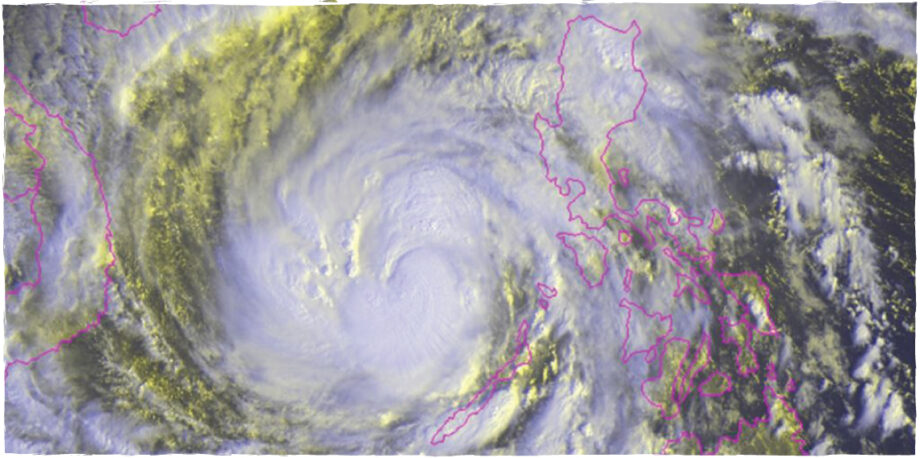

November 18, 2013 — Typhoon Haiyan, considered one of the strongest storms ever recorded, made landfall in the Philippines three days before the United Nations convened in Warsaw for the 19th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 19) on climate change. Many climate policy advocates were quick to call the timing prophetic, pointing to the wreckage of the fatal storm as a wake-up call for the conference delegates to reach a meaningful climate agreement.

U.N. climate chief Christiana Figueres made reference to [PDF] the devastating impact of the typhoon in her opening speech, urging delegates to “go the extra mile” in their negotiations. Olai Ngedikes, the lead negotiator for an alliance of small island nations, said that Typhoon Haiyan “serves as a stark reminder of the cost of inaction on climate change and should serve to motivate our work at Warsaw.” But it was the Filipino delegate to the conference, Yeb Saño, who made the most emotional plea to the delegates. With tears in his eyes, he told the assembly: “What my country is going through as a result of this extreme climate event is madness; the climate crisis is madness.”

Despite the fact that the scientific community has repeatedly cautioned against linking single weather events to climate change [PDF], numerous climate advocacy organizations quickly joined the chorus, arguing a direct link between global warming and Haiyan, urging conference delegates to reach a climate agreement. In an email petition, the online global activist organization Avaaz argued that “Climate change killed [the victims of Haiyan]” and a “greater commitment to fund climate change management efforts is a key piece in the global deal we desperately need to save the world.”

As delegates in Warsaw begin their second week of negotiations, they should consider how greenhouse gas mitigation is tightly linked to the process of development.

The irony of using Typhoon Haiyan as a political tool in Warsaw is that the climate agreement under discussion has very little relevance to protecting the Philippines or other vulnerable nations from climate disasters in the near term or even the medium term. The delegates in Warsaw are passionately pleading to set nonbinding goals on carbon dioxide emissions reductions that wouldn’t begin until 2020. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s projections suggest climate change will not likely begin to alter tropical cyclone intensity and frequency before mid-century. While CO2 emissions are a crucial topic for the global community, the more important goal for a country like the Philippines, whose average resident emits a 10th the carbon of the average European, is basic development, infrastructure and resiliency.

The Philippines and other vulnerable countries need immediate protection against storms like Haiyan, which are happening now and will likely happen again before any emissions reductions go into effect in 2020. The real lesson from Typhoon Haiyan, therefore, is the need for better disaster preparedness infrastructure, including robust surge barriers like the one under construction in Louisiana; modern electricity supply and distribution; robust transportation infrastructure; and well-prepared, noncorrupt disaster response agencies. Indeed, this will mean that the Philippines’ greenhouse gas emissions will rise before they fall as the country builds out its electricity and transportation infrastructure and achieves access to modern energy services. Only such a build-out will protect the Philippines from the consequences of a warming planet.

As delegates in Warsaw begin their second week of negotiations, they should consider how greenhouse gas mitigation is tightly linked to the process of development. The pattern of history shows that countries first must go through a period of rapid energy intensification as they build steel and concrete cities and move to modern infrastructure, before stemming energy demand and reducing emissions. Virtually all industrialized countries, many of which are now reducing their greenhouse gas emissions, have experienced this development trajectory. While today’s industrialization need not emit as much carbon as in the past, industrialization is absolutely essential for future climate mitigation, and for the more immediate needs of storm-vulnerable countries such as the Philippines. ![]()

Editor’s note: The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily of Ensia. We present them to further discussion around important topics. We encourage you to respond with a comment below, following our commenting guidelines, which can be found here. In addition, you might consider submitting a Voices piece of your own. See Ensia’s “Contact” page for submission guidelines.

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!