August 13, 2021 —  Editor’s note: This story is part of a year-long investigation of drinking water contamination across the U.S. The series is supported by funding from the Park Foundation and Water Foundation. Read the launch story, “Thirsting for Solutions,” here and the other stories in the series here.

Editor’s note: This story is part of a year-long investigation of drinking water contamination across the U.S. The series is supported by funding from the Park Foundation and Water Foundation. Read the launch story, “Thirsting for Solutions,” here and the other stories in the series here.

In the 1970s and 80s, an initiative spearheaded by UNICEF drove pipes into the ground in Bangladesh to create tube wells that could tap into the country’s groundwater. These wells provided local people with drinking water that was free of surface water microbes, which had led to children’s deaths due to cholera and other diarrheal diseases.

At the same time, though, the wells introduced another contaminant into the water supply: arsenic, an odorless, tasteless metalloid that is naturally present in Bangladesh’s aquifers, as it is in many other places worldwide. This element is considered a potent carcinogen.

A paper published in 2000 in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization called this outcome “the largest poisoning of a population in history.” And today, tens of millions of Bangladeshis may now face a heightened risk of death due to arsenic exposure.

“It’s a horrible story that taught us a lot about the health effects of arsenic in drinking water,” says Carolyn Murray, a New Hampshire public health and preventive medicine physician and a director at the Community Outreach and Translation Core for the Dartmouth Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research Center, who studies the impact of environmental contaminants in the U.S. — including arsenic — on fetal and childhood development.

A nine-month investigation by the Guardian and Consumer Reports (CR) found alarming levels of forever chemicals, arsenic and lead in samples taken across the U.S. Image courtesy of The Guardian/Consumer Reports Water Investigation

A greater understanding of the devastation wrought by arsenic-tainted water in Bangladesh and other places led to greater scrutiny of arsenic in U.S. water and food supplies — which continues to be an issue, especially in communities most likely to face other social inequalities.

Tightened Regulations, But Disparities Exist

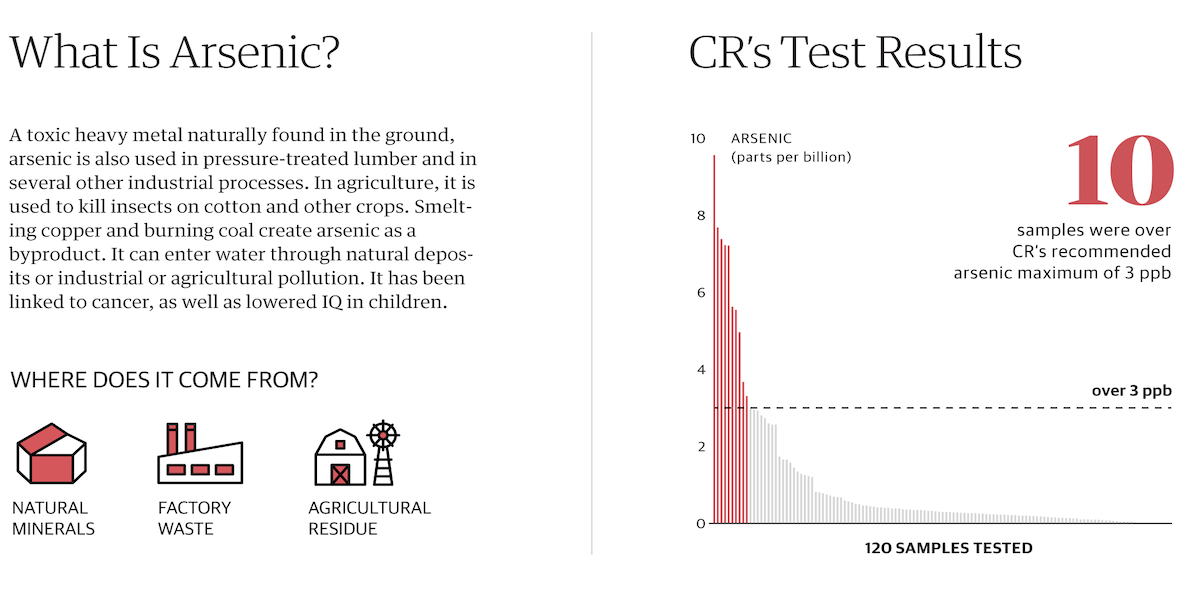

Some arsenic in U.S. drinking water seeps in from rocks and soil, and the element also enters the water through human activities such as industrial pollution and historical pesticide use. (Americans may also be exposed through food that can contain higher levels of arsenic, such as some rice and fruit juice and hijiki seaweed, or through smoking cigarettes.)

In addition to arsenic, lead, copper and manganese are other metals known to have caused contaminated drinking water in the U.S. and elsewhere.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) first limited the maximum contaminant level (MCL) for arsenic in public water systems in the U.S. to 50 parts per billion (ppb), but the EPA’s Final Arsenic Rule, which took effect in January 2006, lowered the arsenic MCL in public water systems to 10 ppb (or 10 micrograms per liter). Today, all but two states use that standard — New Jersey and New Hampshire chose to lower their MCL to 5 ppb. Research suggests that the reduction of MCL from 50 ppb to 10 prevented an estimated 200 to 900 cancer cases per year.

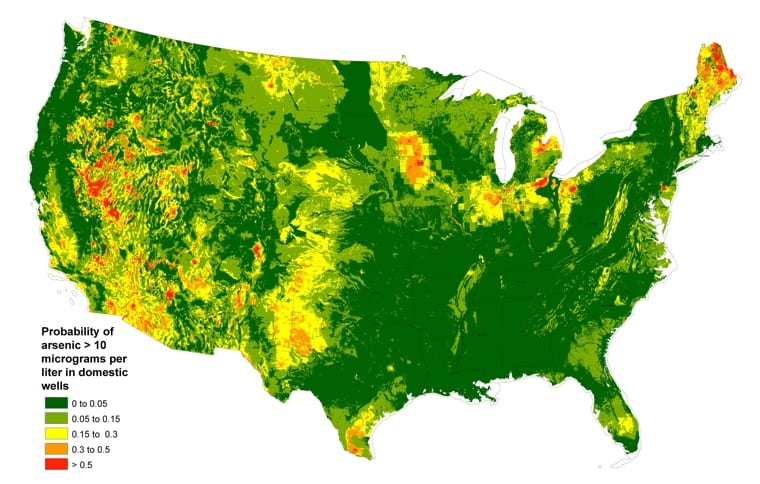

An estimated 2.1 million people in the U.S. still get their drinking water from private wells with high levels of arsenic. Click map to expand. Map courtesy of United States Geological Survey.

Despite these tightened regulations, an estimated 2.1 million people in the U.S. still get their drinking water from private wells with high levels of arsenic, according to a United States Geological Survey (USGS) study, and some public water systems still exceed EPA standards, with exceedences found in places from Kern County, California to Riesel, Texas. The Southwestern U.S. has the highest rates of elevated arsenic in drinking water in the country.

“Arsenic is one of the contaminants most likely to have a violation reported to the EPA across all public water systems in the U.S.,” says Anne Nigra, a postdoctoral research fellow in environmental health sciences at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, and lead author on the first study to assess differences in U.S. public drinking water arsenic exposures by geographic subgroups.

In most cases, the amount of arsenic contaminating U.S. drinking water is still low compared to what was found in Bangladesh, but scientists have been learning that, even at lower levels, exposure to arsenic over long periods of time is associated with a myriad of health effects, including skin cancer, bladder cancer, changes in heart structure, an elevated risk of heart disease and high blood pressure.

In New Hampshire, Maine and Vermont, studies suggest that an elevated risk of bladder cancer (about 20% higher than elsewhere in the country) among the population may be due to the presence of arsenic in drinking water drawn from private wells.

The research by Nigra and researchers indicates that the burden of elevated arsenic in drinking water in the U.S. falls particularly hard on communities that frequently bear the burden of other social inequalities, including semi-urban Hispanic communities, and incarcerated people in the Southwest who have no alternative water source.

“It is a major environmental injustice,” says Nigra.

Inequalities in Public Water Arsenic Concentrations

The study by Nigra and colleagues looked at the inequalities in water arsenic concentrations in public water systems across the U.S., comparing concentration levels from 2006-2008 with 2009-2011, the initial compliance period for the EPA’s MCL of 10 micrograms per liter. The researchers report that despite declines in arsenic concentrations in water systems, some groups were still exposed to arsenic concentrations in drinking water that exceeded the MCL, including Hispanic communities, communities in the Southwestern U.S., those dependent on groundwater, and those serving smaller populations.

Of 18 counties categorized into the High/High compliance category (water arsenic greater than 10 micrograms per liter during both time periods covered by the study), seven — or nearly 40% — were Semi-Urban, Hispanic counties. “These results could have important implications for future efforts aimed at reducing the arsenic MCL further and for the regulation of similar drinking water contaminants,” the researchers write.

A study by Columbia University’s Anne Nigra and others looked at the inequalities in water arsenic concentrations in public water systems across the U.S. Click on the map for an interactive version of this map from the Columbia Arsenic Map. GIF courtesy of Anne Nigra.

Nigra says people in those Hispanic communities with high public drinking water arsenic exposure may also be eating rice as part of their normal diet, which could add to their total arsenic exposure. “It’s potentially a double whammy,” she says.

Water systems serving counties in the study that are classified as “Rural, American Indian” had the second highest average arsenic concentrations, regardless of whether the water systems were tribal or not, Nigra says. However, she says, “because we know we are missing the majority of tribal water systems, this finding may not hold for all American Indian communities. But it is an important observation and finding nonetheless that warrants further investigation.”

In a related paper published in 2020 using the same data set, Nigra and researchers looked specifically at prisons, jails and other correctional facilities with their own water systems in the U.S. Southwest. Those systems fall under the EPA definition of a public water supply, and are subject to EPA regulation. The researchers found that those systems had arsenic exposure levels twice as high as other types of water systems in the Southwest, and that they were significantly more likely to exceed the regulatory standard.

“No public water system should exceed the arsenic regulatory standard,” says Nigra. “That’s very clear. But incarcerated populations are especially susceptible to the adverse impacts of all types of contaminants. And that’s because these communities don’t have alternative drinking water sources or access to water filters. When their water quality is threatened, they have no alternative.”

She continues: “It’s an injustice and inequality that public health researchers and policymakers should really be paying attention to and should be doing everything they can to mitigate, reduce and eliminate as soon as possible.”

Solutions for Public and Private Water Supplies

Public water suppliers that run afoul of MCL standards often must make costly adjustments. On Vashon Island, Washington, for instance, a public well brought online in 2010 to increase the community’s summer water supply cost several hundred thousand dollars and produced nearly four times the MCL for arsenic. It is now blended with surface water from a creek to reduce contamination to the standard.

A public well meant to increase the summer water supply on Vashon Island, Washington, produced nearly four times the maximum contaminant level for arsenic, and is now blended with surface water from a creek to reduce contamination to the standard. Photo courtesy of The West End, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

The Texas town of Riesel, which has been out of compliance with the EPA standard for fifteen years, recently received a US$5.36 million no-interest loan and a US$500,000 grant from the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund in order to drill a new well.

Sometimes it’s the consumers themselves who discover public water violations of the arsenic standard, as well as excesses of other contaminants.

In 2010, Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta, of the University of Arizona Superfund Research Program Center, co-created the Gardenroots project with residents of Dewey-Humboldt, Arizona, a rural community adjacent to the Iron King Mine and Humboldt Smelter Superfund site. Residents wanted to measure arsenic in their soil and home gardens. The elevated arsenic levels they found during the project eventually led to the discovery that the local public water system was exceeding the arsenic drinking water standard. The utility was issued a notice of violation and a fine, and eventually installed a new filtration system, according to Ramírez-Andreotta.

Unfortunately, says Ramírez-Andreotta, the years out of compliance — and a further delay in bringing the water up to EPA standards — broke trust with many residents. “These families have a memory of the utility not meeting the standard and of not being notified of that,” she says. “So they don’t trust the utility anymore and they drink bottled water.”

For the estimated 15% of U.S. residents who get their drinking water from private wells, the solution to elevated arsenic is also often either drinking bottled water, or installing a treatment system, ranging from a point-of-use system that is installed at the kitchen sink and the refrigerator/ice maker to whole-house systems that remove arsenic from bathing water. One water pitcher filter can also remove the contaminant.

Is Any Level Safe?

Some studies suggest that the EPA standard of 10 ppb may not be low enough to provide safe drinking water. New Jersey and New Hampshire have passed statewide MCLs of five micrograms per liter. In the Netherlands, a voluntary agreement among drinking water companies targets an MCL of one microgram per liter. The EPA’s health-based MCL goal for arsenic is zero micrograms per liter, but that number is considered unenforceable.

Murray, the Dartmouth physician, is currently doing research focused on the New Hampshire Birth Cohort Study, which investigates the impact of environmental contaminants such as arsenic on fetal and childhood development. The study recruits women in their second and third trimesters of pregnancy who get their drinking water from private wells and follows their health over time.

“I think we know what we need to know for action to be taken. And there’s no reason why any water system should be exceeding the arsenic Maximum Contaminant Level at 10 micrograms per liter.” –Anne Nigra

“And we keep seeing health effects as we go lower,” she says. “Our findings so far have included evidence of increased risk of lower respiratory tract infections, more antibiotic use and treatment for upper and lower respiratory infections. We’ve also seen some impact on weight and growth that’s consistent with how much exposure the mom and child have had to arsenic in their drinking water.” Multiple researchers in the U.S. are conducting epidemiological studies on possible correlations between arsenic exposure and neurological and cognitive dysfunction.

Murray would like to see a patient’s drinking water source be part of their medical health record, “especially in rural areas where it is more common for people to have private water systems,” she says. She also wants doctors to encourage private well testing.

In the meantime, interventions are a way to reduce exposure to arsenic and other contaminants in water. For example, pregnant women in New Hampshire on the federal Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food assistance program who drink arsenic-tainted well water can now get a free pitcher and filters to remove the contaminant.

For public water systems, Nigra and others say the research is clear enough that all U.S. drinking water should be at — or below — the EPA maximum. “I think we know what we need to know for action to be taken,” says Nigra. “And there’s no reason why any water system should be exceeding the arsenic Maximum Contaminant Level at 10 micrograms per liter.”

The work of reducing drinking water arsenic exposures will likely take many forms. One sometimes overlooked solution, says Ramirez-Andreotta, is in forming partnerships with communities, such as her Gardenroots effort and another recent citizen science effort to inventory water pipes, Crowd the Tap. “Community members are experts in their own right,” she says. “They can generate new knowledge and help translate it into action. We’re focusing right now on vulnerabilities but these communities have a lot of strengths that can propel them to the next level for environmental health.”

Editor’s note: The main image is of Freer Water Control and Improvement District manager Diana Adame, right, and plant worker Anthony Arredondo, comparing a test to a chart that shows arsenic levels in water from Freer, Texas. The original can be found here.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!