May 14, 2021 — Editor’s note: This story was originally published in New Mexico In Depth and is republished here as part of a collaboration, Tapped Out: Power, justice and water in the West, in which eight Institute for Nonprofit News newsrooms — California Health Report and High Country News; SJV Water and the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism; Circle of Blue; Columbia Insight; Ensia; and New Mexico In Depth — spent more than three months reporting on water issues in the Western U.S. The result documents serious concerns including contamination, excessive groundwater pumping and environmental inequity. It was made possible by a grant from The Water Desk, with support from Ensia and INN’s Amplify News Project.

Early this year, five of Gallup, New Mexico’s 16 water wells stopped producing water, including two of its biggest. After a few days of maintenance, two worked. The other three were out of commission for more than a month. Had it happened in summer, the city might have asked residents to dramatically reduce use.

“I’m not in crisis mode,” says Dennis Romero, water and sanitation director for the City of Gallup, but “it could go to crisis mode very quickly.”

The shortage isn’t wholly surprising — 20 years ago, the city decided it could limp along on aging groundwater wells with dropping water levels until a new water project began delivering San Juan River water in late 2024. The project is also connecting nearby Navajo communities, where many residents lack running water, an issue the Navajo Nation says is long past due and in need of a fix. But now a potential four-year delay could force a growing number of people to rely on these strained groundwater sources. A plan to keep taps from running dry will come with a price tag.

The situation highlights how precarious water has become for this city of almost 22,000 in western New Mexico and offers a peek inside the complicated mix of relationships, creativity and familiarity with multiple government agencies that’s required to manage water in the 21st century.

The situation highlights how precarious water has become for this city of almost 22,000 in western New Mexico and offers a peek inside the complicated mix of relationships, creativity and familiarity with multiple government agencies that’s required to manage water in the 21st century.

Gallup sits in the high desert along the red sandstone mesas of the Colorado Plateau. For much of its history, it has functioned as an industrial town and a bustling commercial center. Named in 1881 after railroad paymaster David L. Gallup, freight trains and Amtrak still rumble through, in addition to a steady flow of semi-truck traffic around the exits for Interstate-40. Surrounded by the Navajo Nation, on the first weekend of the month the town swells by 100,000 as people stream in for supplies. Those with no running water at home fill water containers. People do laundry, wash cars, go out to eat.

For decades, the Navajo Nation bordertown has relied on groundwater stored in sandstone layers deep underground. With no nearby rivers, wells tapping that water have been the city’s only option. But because annual rain and snowfall don’t replenish the water, levels have dropped over recent decades. In the 1990s, the city projected shortages by as early as 2010.

“Not only was Gallup running out of water, everybody was running out,” says Marc DePauli, owner of DePauli Engineering and Surveying, which the city has hired to work on the water systems. About 20 smaller surrounding water systems had “straws in the same bucket,” all leaning on dwindling reserves.

Help is coming in the form of the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project, the result of a historic agreement that settled Navajo Nation claims to water in this arid region of the Southwest after decades of discussions.

Consisting of two major pipelines that run through Navajo communities in western New Mexico, the project will bring water from the San Juan River to within reach of some of the one in three homes without it on the Navajo Nation. One of the pipelines, the Cutter Lateral that branches to northwest New Mexico, is complete. The other, the San Juan Lateral, will move 37,700 acre feet (47 million cubic meters) of water each year for 200 miles (322 kilometers) along the western edge of the state, up to 7,500 acre-feet (9 million cubic meters) of which will come as far south as Gallup. In the future, the city will rely largely on water from the San Juan.

Gallup is also set to become a hub for a regional system of water tanks and pipelines that will transport water to nearby Navajo communities, including Church Rock, Yah-ta-hey, Gamerco and Williams Acres. The city will supply those people with water even before San Juan water arrives.

“We’re seeing an increase in water demand without an increase in population simply because these communities and water districts that have done water hauling, that have done small well co-ops, they really want a reliable water supply and they’re looking to us to give it to them — and we want to help them, we’re neighbors,” Romero says.

Workers fill in crevasses inside a holding tank for 2 million gallons that will be piped to Red Rock Chapter and eventually, on to Chi Chil Tah Chapter. Chapters are the most local unit of government on the Navajo Nation. Images courtesy of Marjorie Childress

The water was supposed to flow by 2024, but a new design proposed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation will now likely push that date back by three to four years, putting Gallup in a tight spot, monetarily and water-wise. The construction delay coupled with the city shouldering more demand will require new wells to supply everyone until water from the San Juan arrives.

Possible, if Expensive, Fixes

A shift in the design for where and how river water joins the system has caused the potential wait. The Public Service Company of New Mexico (PNM), the state’s largest utility, is closing the San Juan Generating Station as early as next year and has offered to sell the power plant’s reservoir, which draws from the San Juan, as an alternative staging ground for water for the Navajo-Gallup Water Supply Project.

The benefit to Gallup is negligible, Romero says. But the Bureau of Reclamation believes the change would result in beneficial long-term cost-savings for this massive, over-budget federal project.

Pooling water in a reservoir would enable mud from spring runoff and monsoon storms to settle, saving on costs to make the water safe for human consumption. Using the existing facility could cut US$50 million from construction expenses, according to a 2019 letter from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation to the city.

It also offers a protected reservoir, should the river see another spill like the one in 2015 that flooded the San Juan River with 3 million gallons (11 million liters) of orange, mine-waste-filled water. That’s a priority for tribal members, says Jason John, director of the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources. Without a reservoir, the Navajo Nation would be forced to turn off water to dozens of communities if a similar spill happened.

“We’re trying to make sure we have a project at the end of the day that’s going to be able to provide the water that was promised and to provide that water in a reliable fashion and one that makes sense in terms of operations and maintenance costs as well,” John says.

PNM’s offer came late in the planning process.

“The timing wasn’t the greatest,” says Pat Page, manager of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Four Corners office, which is overseeing the project. But after an initial look at the facilities, “We felt like we couldn’t walk away from that, even as bad as the timing was.”

A more detailed analysis is still wrapping up, Page says, and everything points toward this new option.

The problem is, Gallup developed its current water use plan assuming surface water would arrive by December 31, 2024. Leaning longer on already over-tapped wells puts the city and all its customers, including Navajo communities that have begun buying water from it, at risk.

“A four-year delay is going to be expensive. It’s going to take money and more wells,” says DePauli, the engineer.

The city is already in for US$75 million for the new water system. Now comes an added expense of drilling new wells, at a price of about US$3.5 million each.

When the work is done on the pipeline, operations and maintenance transfer to the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority, and Gallup will contribute to ongoing costs. The Bureau of Reclamation has proposed to reassess Gallup’s share of future utility costs in return for supporting the new water intake system.

The city has recently added to its water rights, positioning it to weather this delay and provide for nearby communities in need, says George Kozeliski, a former city attorney who has worked on water rights for Gallup. The Office of the State Engineer recently approved Gallup’s use of other well fields, with water opening up now that the Escalante Generating Station, just east on Interstate-40 in Prewitt, and Marathon Petroleum’s refinery have shut down. That well field reaches into an aquifer Gallup hadn’t yet tapped, and the city now has rights to more water than its average annual use.

“That aquifer has got a lot of water in it, and these others, if they do fall — and they are falling — then that one can take care of Gallup,” Kozeliski says. “Everybody was worried about the same thing, and I don’t want to say we did a shotgun approach, but everything just kind of came together now.”

But, Romero says, it’s only a right on paper Kozeliski is talking about: The city still needs money to drill wells to access that water.

Gallup began pursuing more groundwater in 1983, but the Navajo Nation and Bureau of Indian Affairs challenged the application to increase the town’s groundwater rights. Last year, after Covid-19 made the need for water even more urgent, both challenges were dropped as Gallup agreed to use some of that water to supply additional Navajo communities.

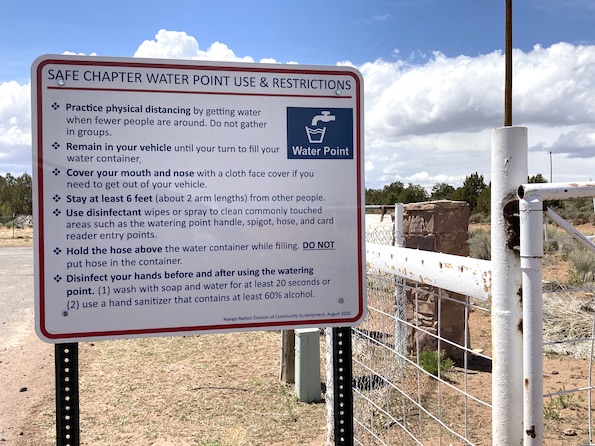

A sign outside the Chi Chil Tah Chapter House explains how to safely fill water containers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Image courtesy of Marjorie Childress

“A lot of Navajos feel like the water in a lot of this region belongs to the Navajo Nation, but we’ve been able to try to set aside some of those long-standing disputes about groundwater,” Jason John says. “We’ve fought very hard to make sure that the city, if it’s going to continue to use water, that some of the use of that water should go to the benefit of Navajo families adjacent to the city of Gallup.”

Tackling Both Long-term Concerns and Immediate Needs

Gallup’s problems are not unique in an increasingly arid Southwest, where cities are facing the need to get creative and think large-scale for solutions as historic water sources dry out. Infrastructure to move water from one place to another based on changing supplies and demand, and solve these problems regionally, not city-by-city, will be key for resilient water supplies in the future, says Kathryn Sorensen, former director of the City of Phoenix Water Resources, and now with the Kyl Center for Water at Arizona State University.

Take Phoenix. For 40 years after the Central Arizona Project began delivering Colorado River water to Phoenix, the city invested hundreds of millions in surface water treatment plants and avoided pumping its aquifer. But it also stopped investing in its wellfield. Now, the amount of water in the Colorado River has decreased and climate change will exacerbate the decline.

“The city of Phoenix found itself in a place where, if shortages got steep enough, it was facing the possibility that it would not be able to get wet water to customers in north Phoenix,” Sorensen says. “That was not acceptable.”

Even rehabbing the old well field in Phoenix didn’t look like a solution. So the city partnered with Tucson, piping some of its Colorado River water to be stored in the aquifer under that city.

“The idea is that when there’s a shortage on Colorado River water, they can call that water back,” Sorensen says.

Gallup is essentially at the spot Phoenix was 40 years ago, but has no plans to give up its well field. In the long run, the city and the communities linked to its supplies may enjoy the position of using river water when available and well water as needed. It’s the wait until then that’s tough.

Gallup uses wells that were originally drilled in the 1800s for railroad steam engines. The city recently rehabbed this well, sinking a new pump and motor from about 800 to 1,200 feet. Image courtesy of Marjorie Childress

Already, Gallup is a go-to source in the region among communities that don’t yet have water piped in and rely on hauling. At the height of the summer, almost 2 million gallons (7.6 million liters) of water are pulled from the town’s water loading station each month. When Gallup shut down for two weeks in May 2020 to slow the rampant spread of Covid-19, people contacted Romero concerned that the barricaded roads would cut people off from that water station. The Albuquerque-Bernalillo County Water Authority sent out three 10,000-gallon (38,000-liter) tankers, he says, creating two watering points just outside city limits.

Now, that role is expanding, as construction work around the city reaches nearby Navajo communities, some of which still have a high percentage of residents living without reliable water sources at home. As soon as those pipes are finished, they’re immediately “wet” from the city’s groundwater wells, Romero says, which puts more and more people leaning on a decreasing source. A few are online, and more are coming or interested to link in.

“Realistically speaking, we have these communities that are starting to knock on the door and saying, ‘We’re going to be ready for water in a year or two,’” Romero says.

The Navajo Nation and the city are collaborating on that effort. But what communities do until then is still a problem.

“The water line from north of Gallup, the plan was that it wouldn’t reach us until like 2026 or something like that,” says Roselyn John, community services coordinator for Chi Chil Tah, a Navajo chapter south of Gallup. “It was way into the future, and we couldn’t wait that long, so we started doing a different approach.”

In Chi Chil Tah, 137 homes, each with between three and nine residents, are without running water. Some chapter residents who bought mobile homes as recently as five years ago have ripped out the bathrooms to make other use of the space, John says.

Roselyn John, left, community services coordinator, and Melita Martinez, accountant, describe a planned water system that will connect homes in Chi Chil Tah, a Navajo chapter, to a community well. The community was hard hit by the COVID-19 pandemic, and John said a lack of water was one of the reasons. Image courtesy of Marjorie Childress

Residents often drive 27 miles (44 kilometers) to Gallup on roads they may have to shovel snow off, fill a 250-gallon (946-liter) water container, and drive back, a trip that takes about two hours. For others, a watering station at the chapterhouse is closer.

Water piped from a storage tank miles north flows to a small pump and into a garden hose at the chapterhouse. Filling a 250-gallon (946-liter) container takes 15 to 20 minutes, and as people stack up, the line stretches down the road for a mile. The absence of running water at home to wash their hands, which forced them to go to a water station to replenish, counted among the factors that let Covid-19 spread, hitting the community hard.

“There are plans to get water through the Navajo-Gallup project to them, it’s just a matter of timing and their current need for water,” says Jason John, with the Navajo Nation Department of Water Resources. Given how long it will be before water could arrive from the Navajo-Gallup Project, he says, “We’ve made plans for the possibility of having to supply them with groundwater until the Navajo-Gallup project comes online.”

Chi Chil Tah has secured money from the state of New Mexico for groundwater wells, the first of which could be drilled as soon as this summer. That’s when they’ll find out how much water a well can produce, and whether it’s good to drink. The well for the Family Dollar, one of the few nearby businesses, produces poor quality water, so the hope is these new wells access better water, and more of it.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!