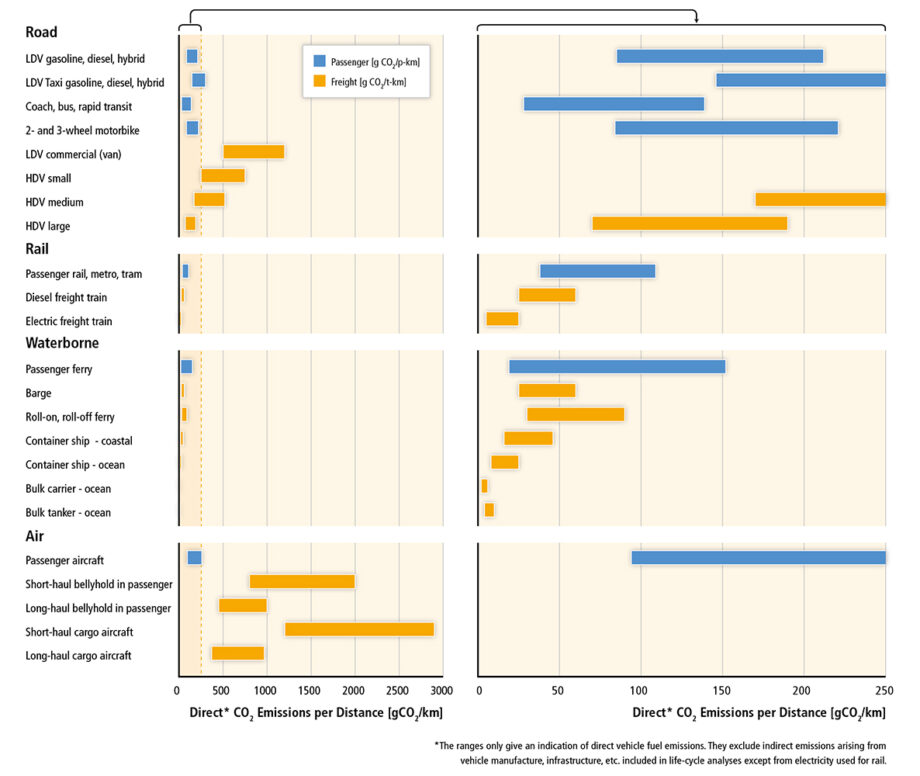

September 18, 2019 — In early June 2019, the three of us were having a conversation at the University of British Columbia when Lior expressed some dissatisfaction about an activity at his kids’ school that suggested airplane travel is bad for the climate. In fact, he said, per passenger mile, air travel carbon emissions are of the same order of magnitude as other modes of transportation, so it doesn’t matter  much whether you drive or fly. However, he further explained, since larger planes are more carbon-efficient and since takeoff and landing are particularly costly, the carbon efficiency of air travel significantly depends on distance. In other words, short-haul flights tend to be inefficient relative to driving, while transcontinental flights are very efficient.

much whether you drive or fly. However, he further explained, since larger planes are more carbon-efficient and since takeoff and landing are particularly costly, the carbon efficiency of air travel significantly depends on distance. In other words, short-haul flights tend to be inefficient relative to driving, while transcontinental flights are very efficient.

The other two of us looked at each other, bewildered. We had both calculated our carbon budgets and seen that a single transatlantic flight would blow our annual carbon budget. Many prominent climate scientists were touting #flyingless. But was Lior right? Had we been drinking flight-shaming Kool-Aid?

That evening, we looked up the numbers on Wikipedia and found, to our surprise, that Lior seemed right! At least to some extent. We tweeted about it to let the experts weigh in.

.@NRamankutty & I have a #flyingless question.

First, CO2 emissions by transport mode:

air~0.18-0.24 kg CO2/passenger mile

car~0.13-0.44

bus~0.3

rail~0.19-0.2

These look similar to me.

Is the problem flying, or should we be talking about #travelless?

Or am I missing something?— ElenaBennett (@ElenaBennett) June 5, 2019

Quickly, the Twitter community pointed us to more accurate data, and engaged in nuanced discussions. This essay is a summary of what we learned.

1. Mode of transportation is less important than distance traveled (with some key exceptions)

Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment of Climate Change (2014). Click to expand.

2. Energy source matters

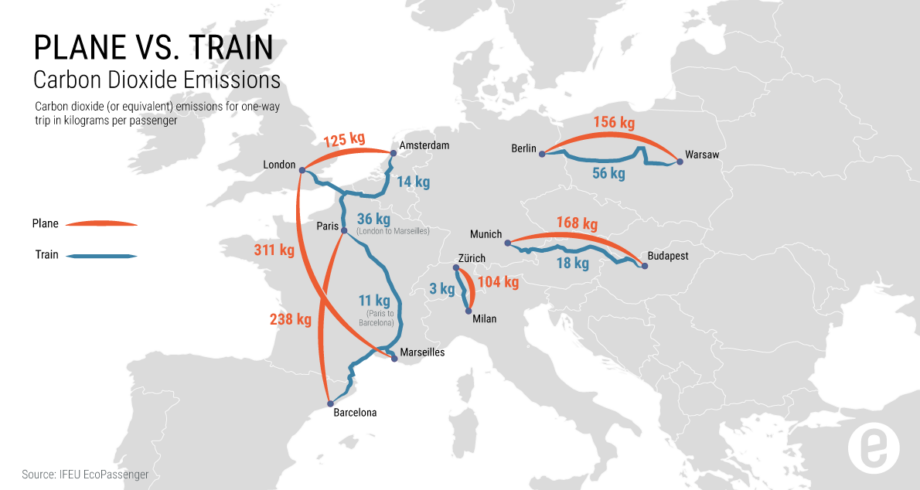

While the IPCC figure suggests that trains aren’t much better than planes, many Europeans responded to our tweets with figures showing a big difference (see below). What’s going on here? Turns out that trains in Europe are mainly electrified, with a recent push to supply them with energy from renewable sources, while those in North America use fossil fuels (often diesel). In Europe, trains are by far the best choice in terms of climate benefits, even if that’s not as true elsewhere.

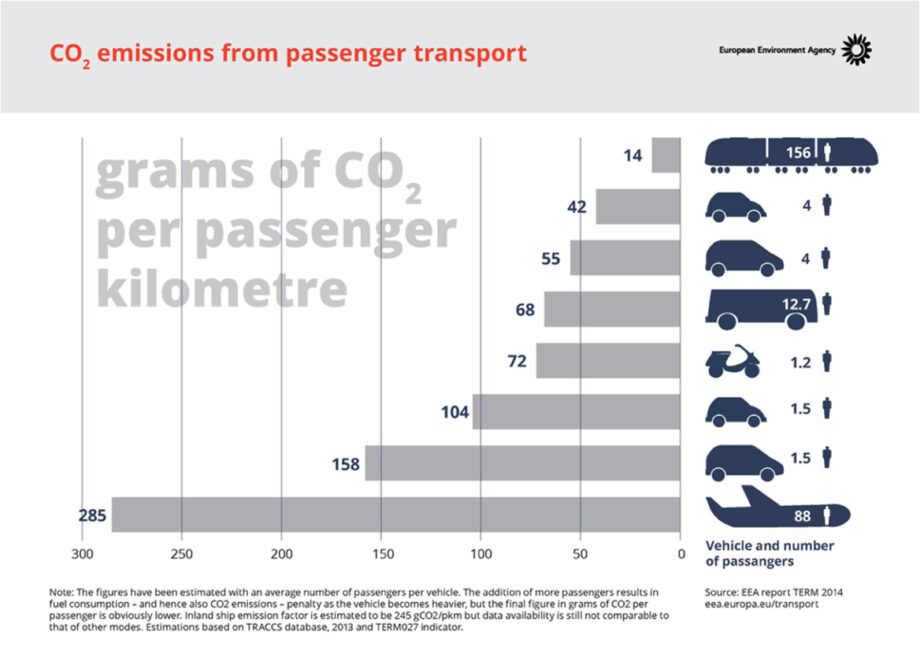

3. Passenger number matters, too

All of the above estimates of emissions are reported per passenger. However, the data don’t indicate the assumptions made about how many people are in the car, train or plane. But other graphs are explicit, and show how emissions vary along those assumptions. The figure below clearly shows the assumption that on average a train will have 156 people; a plane, 88; and a bus, 12.7. It also shows how car emissions vary by the size of the car and the number of people in the car. In North America, given the similarity of emissions per kilometer among car, train and plane, it might be more important to carpool than to find another mode of transportation.

4. Marginal effects need to be considered

Public transit runs based on expected average number of passengers, whether you personally use it or not. It will require large shifts in numbers of passengers to change the numbers of buses, trains or planes running. An individual’s decision to take or not take public transit does not affect the emissions of that trip. But a decision to drive does. So, if you choose to drive because it is more climate friendly than flying short-haul, you are adding an extra car on the road while the plane would have flown anyway. However, in the long run, if many people choose to drive (hopefully in a full car), it is likely there will be fewer short-haul flights.

5. Short-term effects differ from long-term effects

Trends suggest that ground transportation is increasingly being electrified (with the potential for using renewable sources). However, there is likely no such technological breakthrough on the horizon for planes. Thus, flying less is an important long-term commitment because it helps to make sure there are more alternative transportation options, and shows where we want government and industry to prioritize efforts toward efficiency and transit.

6. The bigger picture is important

While we want to reduce the climate impacts of aviation, we need to remember that flying produces only 2% of total emissions today. Even if everyone were to stop flying, the total climate mitigation impact would be negligible. While flying is the biggest culprit in terms of climate impacts for those who can afford to fly (including most climate scientists), the majority of the world’s people do not fly and road transportation remains the largest share of transportation emissions. While refusing to fly does send an important message, it’s important to make sure a narrow focus on flight emissions doesn’t cause us to lose sight of the need for impactful climate action in multiple sectors.

7. Our decisions are not all just about climate change

Navin’s mother lives in India. Elena has family in the United States. Lior has family in Israel. We all have friends all over the planet. Science is also a social endeavor, and it is hard to replace face-to-face gatherings with telepresence. Feeding our souls with family and friends and collaborating on our work requires travel, and sometimes the only way to get to these people or events is on a plane.

So, where does all of this leave us?

First, we should be thoughtful and selective about traveling. “Meaningful travel” (#travelless) means carefully considering whether a trip is worth the climate impacts.

Second, when we do decide to travel, we should try to bundle trips.

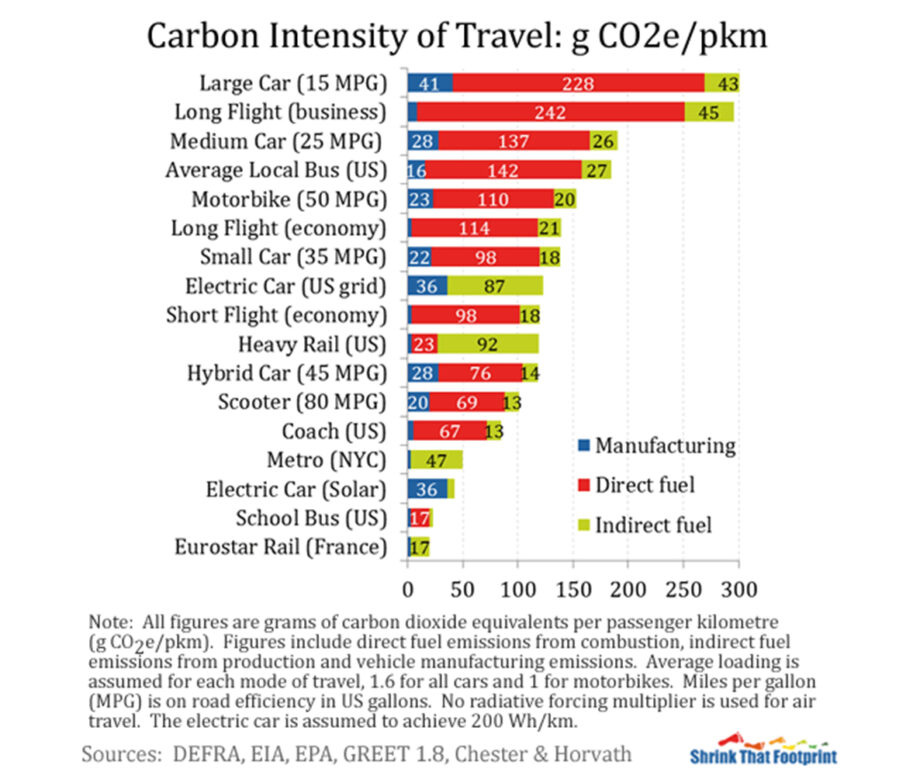

Third, we should choose a mode of transportation based on all the considerations mentioned above. The chart below presents a nice summary of many of the issues we discussed for consideration. (This figure suggests that shorter flights are less carbon intensive than long haul. This is because of the assumption in the analysis that “Short flights (less than 3700 km [2,300 miles]) are often less carbon intensive than long flights (greater than 3700 km) because they generally have higher occupancy and lighter fuel loads. This doesn’t hold for very short flights (less than 1000 km [621 miles]) which are in fact more carbon intensive as they spend little time cruising, and are often not very direct.”)

Finally, we should consider offsetting our travel impact by contributing to a better world. Navin concluded, after another twitter thread on this question, that we can do three things: 1) offset our carbon emissions; 2) contribute to an organization that is driving political action to solve climate change; and 3) contribute to a humanitarian organization, because the people most affected by climate change are the world’s poor already living at the margins.

Editor’s note: For more on this topic, the authors recommend “Fly or drive? Parsing the evolving climate math,” “Aviation Q&A: the impact of flying on the environment,” and “Getting there greener: The guide to your lower-carbon vacation.”

To read more of Ensia’s coverage as part of Covering Climate Now, click here.

The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily of Ensia. We present them to further discussion around important topics. We encourage you to respond with a comment below following our commenting guidelines, which can be found on this page. In addition, you might consider submitting a Voices piece of your own. See Ensia’s Contact page for submission guidelines.

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

Original text: "Another comprehensive study (http://bit.ly/30zovHu) considered not only the climate impact of carbon dioxide emissions, but also other climate impacts such as short-lived warming due to contrails and cirrus cloud formation associated with airplanes, or the cooling effect of sulfate aerosol formation from shipping or rail transport. While aviation impacts are much larger than other modes in the short-term (<5 years), in the long term (50-years), the difference between aviation and other modes of transport are not that large (see their figure 1 showing that rail climate impact is about 40% of aviation)."

Your argument about road emission stands and a macro level is justified, however on an individual level, what matters is the marginal increase of emissions. In other words, we should reduce both road and air emissions, but if you had to take one or the other bad pull, it is better for the earth to use a car (on average).

2% is "negligible"??? When are we going to stop saying things like this. 2% is NOT negligible. An individuals efforts are important.

Also, there are numerous opportunities to reduce inefficiency that would reduce travel and domestic energy footprint similar amounts, but require negligible input...but a lot of education/promotion.

A favorite of mine is to consider the massive number of pots of grains cooked daily, globally. Most people I know maintain heating their pot of grain for 15-60 minutes, when most the actual need for energy is the initial boiling of the water. In other words, as soon as the grain reaches boiling, a lidded pot will in almost every case steam itself to perfection with no further energy input.

(additional benefit can be derived by boiling the water in an electric kettle to begin with--how I always heat water with which I am cooking)

Add to that 1) zero food waste from burning grains, 2) negligible cleaning product use/need, and 3) not having to build those ridiculous plastic/metal/electronics (landfill-in-waiting!) rice cookers.

My estimation is that, assuming 3 billion pots of grains daily, reducing this energy need by 70-80% by this efficient steaming method could very well reduce human energy footprint by 1-1.5%.

It doesn't sound like much, but it also seems to me like it could be preventing the straw that broke the camel's back.

Thanks for accepting this non-travel energy comment--I do not consider any energy efficiency discussion would intend to ignore other readily available forms of remediation in this era of climate crisis.