April 26, 2018 — Imagine discovering that a U.S. government agency was operating a 90-year-old program designed with the best of intentions, but wasted a precious commodity. Suppose, for example, that to help out wheat farmers during the Great Depression, the Department of Agriculture began to buy wheat, ship it down the Mississippi River, and dump it into the Gulf of Mexico. And suppose you learned it was still going on today, nearly a century later.

Believe it or not, that is a good analogy for what is happening today with the Mississippi River. Right now, 100 million tons (90 million metric tons) of suspended sediment flow downriver annually, destined for the gulf and guided by levees built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in response to the great flood of 1927. While this complex levee system helped reduce flood-related problems, it also contributed to conditions that have allowed the loss of 40 percent of America’s coastal wetlands.

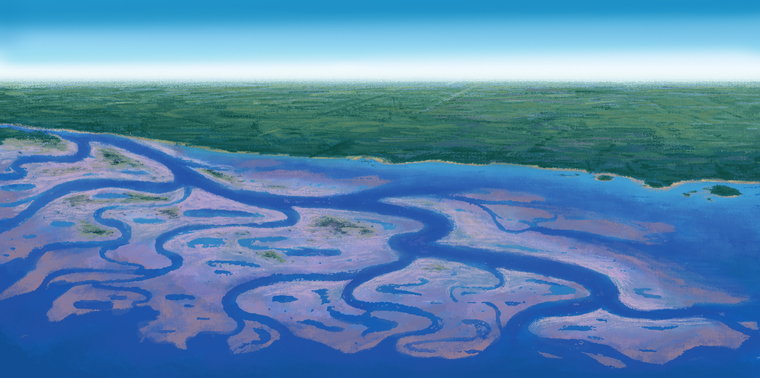

For thousands of years before the levees’ construction, the river’s mouth whipped across Louisiana’s coast like the nozzle of a loose garden hose, constantly seeking the easiest path to the gulf. Depositing fresh water and sediment into shallow bays, it steadily built the Mississippi River Delta, which comprises some of the most ecologically and economically productive wetlands on Earth. Countless wildlife, billions of dollars of navigation and petrochemical interests, world-renowned commercial and recreational salt and freshwater fisheries, unique cultures, musical traditions and cuisines — all of these were born of, and remain dependent on, that great delta.

More than 2,000 square miles (5,000 square kilometers) are already gone, and we continue to lose a football field of land every 100 minutes.But when the levees straightjacketed the river, they not only controlled floods but also halted this natural land-building process and cut the river off from its wetlands. As a result, the land is now sinking and eroding, vanishing before our eyes. More than 2,000 square miles (5,000 square kilometers) are already gone, and we continue to lose a football field of land every 100 minutes.

This spring, heavy rain and melting snow throughout the Midwest have caused the Mississippi River to flood. In response, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers opened the Bonnet Carré Spillway — a flood-control structure located just northwest of New Orleans — for a few weeks in March, decreasing pressure on New Orleans’ levees and diverting water and up to 100,000 tons (90,000 metric tons) of sediment per day from the muddy Mississippi flow into Lake Pontchartrain.

Decreasing pressure on the levees was a much-needed move. Sending the water into Lake Pontchartrain was not. Instead, we should have used it to build and sustain wetlands in nearby basins. We wasted the retail value equivalent of $1.2 million worth of sediment per day while the spillway was open. And that does not even begin to measure the economic value of the healthier ecosystem that sediment could create.

What might we have done instead? If the Mississippi River infrastructure included sediment diversions — structures built into the levee system that can direct water and sediment from the Mississippi into nearby areas suffering land loss when the river is high — we could have used the floodwaters to mimic the natural delta-building process, reconnect the river with its wetlands and rebuild coastal wetlands.

Congress has already directed the Army Corps of Engineers to add ecosystem restoration to its flood control and navigation mission. And it recently passed a bill that increased funding for the corps to deal with aging systems, the levees that channel the Mississippi River.

It is time to use sediment diversions to move beyond the old, tired paradigm of managing the river for flood protection and navigation alone toward a future that restores and protects ecosystems as well. It is time for us to use lessons from decades of managing the river system, as well as the power of the river itself, to address the collapse of the Mississippi River Delta we have caused. It is time to use sediment diversions to move beyond the old, tired paradigm of managing the river for flood protection and navigation alone toward a future that restores and protects ecosystems as well.

Can the corps that tamed the great river for flood control and navigation rethink the purpose and advisability of the current outdated, expensive-to-maintain, and counterproductive crumbling infrastructure and include sediment diversions and other strategies that embrace ecosystem restoration in its upgrade plans?

If it can, the current focus on infrastructure could spell the beginning of an exciting, new, restorative era for the Mississippi River Delta. If it can’t, then perhaps U.S. Rep. Bill Shuster, retiring chairman of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, is right when he questions whether the Army Corps of Engineers is the right agency for managing our nation’s river infrastructure needs. ![]()

Editor’s note: The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily of Ensia. We present them to further discussion around important topics. We encourage you to respond with a comment below, following our commenting guidelines, which can be found on this page. In addition, you might consider submitting a Voices piece of your own. See Ensia’s Contact page for submission guidelines.

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!

Highly successful, rather small sustainable projects, initiated & completed soon after Hurricane Katrina. Specialized containers were designed and applied. The plans & methods demonstrate Nature-cooperative values.

In restorative remediation work, after the Deepwater Horizon estuary & shoreline damages that caused shoreline losses of well rooted, stabilizing plants, similar Nature-cooperative design worked.

Clearly, the values of a “softer engineering” approach can be seen in quickly restored natural shorelines, reestablished by methods focused on correct planting of deeply rooting plants, natural to effected areas.