March 5, 2018 — On a blustery January day at Seahurst Park, a tree-fringed shoreline in the town of Burien just south of Seattle, Jason Toft searches for a promising beach log among the many specimens at hand. Beachgoers sit or climb on top of these washed-up pieces of wood, but Toft, a research scientist at the University of Washington School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, is more interested in their undersides.

He squats in the sand, rolls back a fire-log-size chunk of driftwood with gloved hands, and scrapes back a tuft of beach wrack on the sand beneath it — a mix of green eelgrass and bits of red algae, sprinkled with twigs and leaves; a fertile meeting of land and sea.

“There they are,” he says, pointing at the hollowed-out sand beneath, which is teeming with beach hoppers. Protected by vegetation and beach logs, these tiny creatures burrow in the sand and feed on beach detritus. They, too, are food: In Alaska, where hoppers are known colloquially as “grizzly popcorn,” bears scoop up pawfuls of them for a dietary supplement. Here on Puget Sound they are a vital part of the food web, providing sustenance for birds and fish, including young Chinook salmon, a totemic and threatened Pacific Northwest species.

Scientist Jason Toft surveys the habitat created when living shoreline protection replaced a seawall along the Washington coast. Photo courtesy of Kathleen Pozarycki

This seems an idyllic place, where nature is in balance with itself. Yet, just a dozen years ago, this beach was nearly bare of driftwood or beach wrack, and sheltered many fewer invertebrates like those hoppers. A seawall along this nearly mile-long stretch of shoreline encroached on the beach, narrowing its size, changing its character, and making it nearly impossible for driftwood or wrack to settle.

This is true on many of Puget Sound shorelines with seawalls, rip-rap (jumbled boulders) or other forms of what’s often called shoreline armoring. A 2016 paper describes detailed research led by Toft’s colleague, University of Washington research professor Megan Dethier, that shows how Puget Sound armoring can change everything from the texture of the beach (beaches get coarser, with less sand and more cobble) to the presence of logs and washed up plant life. The more armoring along a stretch of beach, the more impact it has.

Conventional shoreline armoring helps prevent erosion, but it can also reduce the quality of coastline habitat. © iStockphoto.com | gmc3101

In many cases, armoring can temporarily protect land — and structures — from erosion. But it’s also a problem at marine and freshwater shorelines across the country. Armoring puts a wall between the upland shore and the water, creating a disconnect and often loss of important habitat such as wetlands. A National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)–funded study found that shoreline hardening, particularly rip-rap, was associated with a reduced abundance of vegetation even below the water’s surface, such as the eelgrass that shelters juvenile fish, crustaceans and shellfish and helps ecosystems function in other ways. Along beaches with seawalls, researchers find less diversity in fish and invertebrates.

Seahurst’s wall was created, along with the park itself, in the 1970s. “I think it just was the culture of the time,” says Toft of the wall, which wasn’t serving much practical purpose, but looked tidy — at least until it began to crumble.

When that happened, Burien started removing it in two phases, starting in late 2004. The liberated beach was then “nourished,” in restoration parlance, with sediment and gravel, and strewn with logs.

“It’s kind of a perfect situation,” says Toft, gesturing toward the larger beach, a picture-perfect crescent with a distant view of islands and a gleaming white and green ferry. “Why pay for the maintenance of that armoring that’s falling down if we can remove it and just allow this to happen?”

A Watershed Moment

Some 14 percent — or 14,000 miles (23,000 kilometers) — of U.S. tidal shoreline is currently behind some form of shoreline armoring, put in place by both local and federal governments and private landowners. This number is projected to grow as sea levels rise and more severe storms give shoreline property owners more to worry about and as more properties are built in shoreline locations that are vulnerable to erosion. If trends continue, researchers estimate up to one-third of U.S. shorelines could be armored by 2100.

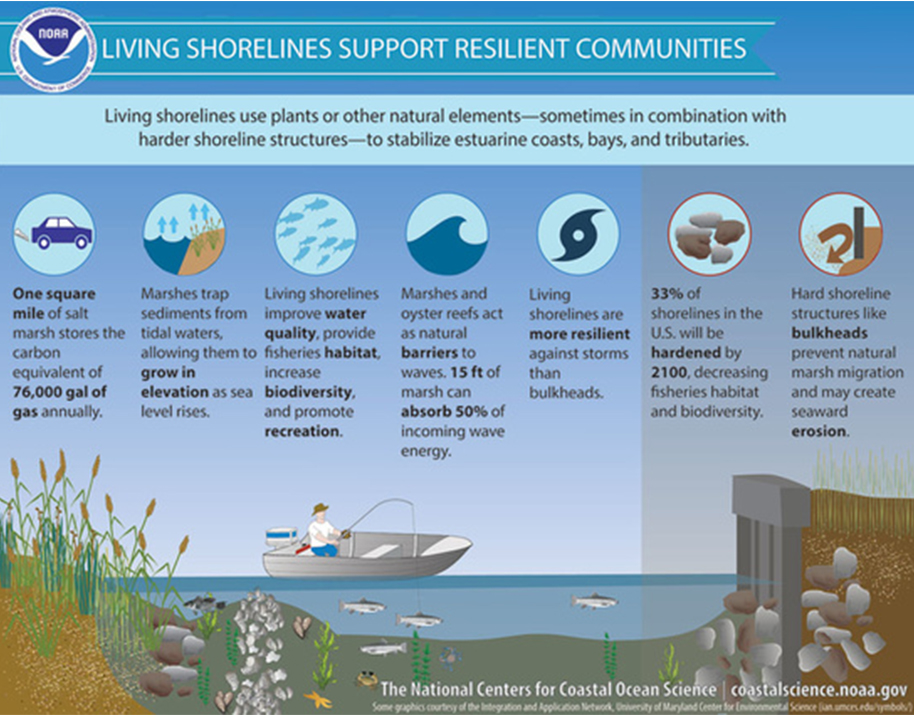

Hard structures like sea walls were once seen as the single method to slow or control erosion. Many examples of armoring were installed long before scientists learned how the structures impact beach and intertidal habitat. Now, researchers are developing nature-based alternatives that can be more effective at storm protection in some locations than shoreline armoring, allowing a movement towards “living” or “softer” shorelines to take hold along many coastlines. These nature-based protections are region-specific and can be a simpler beach nourishment, as at Seahurst, or include mangroves, coral reefs, saltmarshes, oyster reefs or even a hybrid of these with some harder components.

Listen: NOAA scientist Carolyn Currin describes what living shorelines are and the benefits they offer.

“It’s really a watershed moment,” says Donna Marie Bilkovic, a research professor at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science studying coastal ecosystems and lead editor of the 2017 book Living Shorelines: The Science and Management of Nature-based Coastal Protection. “In the past couple of years, living shoreline projects have gotten a lot more attention.” She says that people began questioning the use of armoring in the 1970s, and that on Chesapeake Bay, where the institute is located, living shorelines have been in place for many years.

“Living shorelines are seen as an approach that both protects coastal communities and private property as well as maintains ecosystems, fishery habitat and water quality,” says NOAA scientist Carolyn Currin.

In late 2017, for example, New York State unveiled guidance for living shorelines in the state, encouraging nature-based answers to controlling shoreline erosion in the wake of recent hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria. Some coastal states and federal agencies even provide incentives for communities and private landowners to invest in these projects, such as expedited permits, low-interest loans, tax breaks and federal funding.

There are some unlikely partners. For instance, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, known in the past for canals, dams and other distinctly “hard” structures, has been supportive of the concept and in 2017 issued a streamlined permit specifically for living shoreline projects. The Department of Defense has used hybrid living shoreline techniques to stop erosion while improving habitat at several sites, such as installing shell-based reefs for oysters at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa (see video above).

Some municipalities have even established regulations to make armoring a last resort. For example, Maryland’s living shorelines regulations require shoreline property owners who want to install structural stabilization to obtain a waiver from the requirement to use a living shoreline instead.

Better Protection

While habitat improvement is a big benefit of living shorelines, one of the major reasons they’re getting attention today is research showing how effective they can be in protecting property from storms. “We started to learn that some of these natural habitats were providing even better storm protection because they were more resilient,” says Bilkovic. “A bulkhead may fail during a storm, whereas a marsh is able to bounce back really quickly.”

Unlike seawalls, living shorelines such as salt marshes also reduce the force of waves before they reach the shore, in part by capturing natural sediment that builds up and raises the elevation of the seafloor near the coast.

Additionally, salt marsh meadows may help slow climate change — one of the drivers of some storms — by storing carbon dioxide. According to research published last year by University of California, Santa Cruz, civil and coastal engineer Siddharth Narayan and colleagues, coastal wetlands have protected many properties from flood damage during storm events, specifically helping property owners avoid US$625 million in direct flood damages during Hurricane Sandy. The researchers estimate a 16 percent average reduction in annual flood losses — and up to 70 percent in some locations — in Ocean County, New Jersey, due to the presence of salt marshes, indicating that wetlands help protect shorelines outside major storm events, too.

Additionally, salt marsh meadows may help slow climate change — one of the drivers of some storms — by storing carbon dioxide. According to NOAA researcher Jenny L. Davis and colleagues, salt marshes can store more carbon per acre over the course of a year than mature tropical forests.

Armor’s Place

Living shorelines may be gaining ground, but there are places where armoring is likely to stay, say experts, such as at marinas, or along coastal train routes. And many cities depend on an armored waterfront.

Even in such spots, however, designers are devising strategies to soften the hard edge. Toft and colleagues are working with the Washington State Department of Transportation on studying ways to adapt a 7,000-foot-long (2,000-meter-long) replacement seawall under construction in Seattle to be more fish-friendly. This includes adding features such as a texture that encourages algae and barnacles to attach and create habitat, and installing glass panels to walkways over the wall to allow light to penetrate the water below, attracting fish.

“One of the biggest barriers is people’s perception of effective shoreline hardening.” – Carolyn Currin Yet, according to several experts, one of the biggest hurdles to halting or removing armoring isn’t a lack of good options for doing so, but a, well, hardened idea of what makes a shoreline secure. It can be challenging to explain that the more varied, responsive qualities of a living shoreline can sometimes offer more protection than the blunt force of a wall.

“One of the biggest barriers is people’s perception of effective shoreline hardening,” says NOAA’s Currin, “because people are very accustomed to seeing armoring. I think the first response for many people is, ‘I want what I see’ — which makes sense.”

Perhaps soon what people will see — and want — will be more living shorelines. ![]()

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!