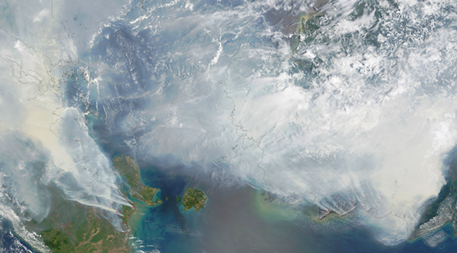

August 10, 2017 — Two years ago, Indonesia experienced the largest fire event in modern human history, with more than 2.5 million hectares (6 million acres) of tropical landscape burning, emitting more greenhouse gases than all of Germany does in a year. But the most visible sign of the disaster was the haze that spread across a huge swath of Asia; the particulates in the smoke sullying the air that tens of millions of people breathed. According to one study, the haze resulted in an estimated 100,000 deaths.

It was a watershed moment — and one the world knew could not be repeated as global attention focused on the role forests play in regulating climate during that year’s COP-21 climate conference. Fires in the tropics are dangerous, emitting huge amounts of greenhouse gases and releasing toxins, especially when they sit atop carbon-dense peat bogs. But these disasters have become commonplace in Indonesia due to exploitation of peatlands.

“The root cause of this crisis was forest clearance and peatland drainage at large scale by the plantation sector, which has turned previously valuable ecosystems into huge monoculture plantations, while leaving remaining forests and peatland at high risk of burning,” says Annisa Rahmawati, forests campaigner at Greenpeace Southeast Asia. For years, both palm oil and paper pulp industries built canals to drain peatlands across the country to expand production, which cause them to turn from wet landscapes to dry ones, ready to burn.

“Fires were a symptom of failed policies,” says Arief Wijaya, senior manager for climate and forests at the World Resources Institute Indonesia. “How the government managed land use was not effective.”

Historically, agencies at national and local levels distributed land to smallholders and large plantation companies under a patchwork system with no comprehensive national oversight. The result was overlapping and conflicting boundaries, making it impossible to determine who controls burned land.

Fixing decades of mismanagement is a tall task, which is why Nazir Foead, head of the Indonesian government’s new Peatland Restoration Agency, known as BRG, raised so many eyebrows earlier this year when he promised neighboring countries a haze-free 2017. Could Indonesia, in just two years, really have made so much progress?

While eliminating all fires and haze in such a short time might be a stretch, even observers in neighboring nations, who have suffered the health and economic consequences of haze and previously criticized Indonesia, agree that there are signs of real change.

“Singapore is glad to see Indonesia make such efforts,” says Pek Shibao, policy research analyst for sustainability at the Singapore Institute of International Affairs. “We believe that as a result of these efforts, future haze events, if any, will likely be of reduced intensity and duration as compared to that of 2015.”

Real Action

Since deforestation became widespread in Indonesia in the early 1990s, nearly every El Niño event, which results in lower rainfall in much of Indonesia, has meant massive fires and haze. It happened in 1998 and again in 2006. Both times, the government made proclamations that the country would act. And yet, when the next El Niño came, not only had little been done, the situation was worse. In 2015, Indonesia’s dried out landscape was a ticking time bomb, and it went off.

This NASA satellite image shows the haze from Indonesia’s 2015 fires over that country and its neighbors. Photo Courtesy of Adam Voiland (NASA Earth Observatory) and Jeff Schmaltz (LANCE MODIS Rapid Response)

But the response this time was different. Indonesia’s new president, Joko “Jokowi” Widodo — a populist elected due to his image as an uncorrupted, effective politician who happened to study forestry at Gadjah Mada University — immediately took action.

“In 2015, there was a public outrage with regards to the fires, so a lot of commitments and promises were being put out,” says Almo Pradana, energy and climate manager at WRI Indonesia.

Robert Field, an associate research scientist at Columbia University with expertise in Indonesian fires, says that the commitments in 2015 went beyond rhetoric.

“The response afterwards was different from previous events,” he says. “And it came right from the top.”

Experts say there are two main aspects of the post-haze push. One is to restore degraded land. To address this, Jokowi announced the creation of the BRG, headed by Nazir Foead, formerly the conservation director at World Wildlife Fund Indonesia, with a mandate to restore 2 million hectares (5 million acres) of degraded peatland across the country. The agency has said the plan is to restore 700,000 hectares (more than 1,700,000 acres) by the end of this year by building 20,000 dams to block drainage canals and using land swaps to encourage those currently planting on high-carbon peatland to move to already cleared or degraded areas.

“To tackle fires, we first need to know who controls the land where they are happening.” –Annisa Rahmawati

The other focus, which is potentially an even bigger challenge, is fixing the country’s broken land management system and improving the ability of government officials at all levels to monitor and respond to practices that could or do lead to fires.

Since the 2015 fires, Indonesia has put into place a moratorium on new palm oil permits aimed at preventing more drainings of peatlands, expanded efforts to map peat and increased investment in fire prevention and monitoring. One concern, says Greenpeace’s Rahmawati, remains the lack of action around haphazard land management. “To tackle fires, we first need to know who controls the land where they are happening,” says Rahmawati. “Unfortunately, the reluctance from parts of the Indonesian government to put accurate concession maps in the public domain makes it harder to identify those responsible for the fires or the destructive practices that cause them.” Greenpeace is calling on the government to speed up its promised One Map — a single, cross-agency land concession map — which would clarify some of these issues and allow for real fire and haze accountability.

The Ultimate Test

2017 will not be an El Niño year, meaning there won’t be the extreme dry conditions that created such a perfect storm in 2015. While the restoration efforts may be having some effect, determining if less haze is due to higher rainfall or efforts being taken by the Indonesian government is tough.

For once, scientists, environmentalists and even neighboring nations are cautiously optimistic.

“As far as the rehabilitation goes, it’s currently too wet for any serious burning to happen,” says Field. “We will only know once we go through another dry year what progress has been made.”

That may come sooner than expected, due to changes in the El Niño–Southern Oscillation cycle, a warming and cooling cycle in the Pacific Ocean that directly impacts rainfall amounts in Indonesia.

“Based on the latest projections, by 2019 there will be another El Niño event,” says Wijaya.

That will be the ultimate test of whether the restoration efforts and top-down structural changes implemented since 2015 have made a difference. When fires rage, Indonesia is the world’s fourth largest emitter of greenhouse gases, the majority of which come from land-use changes directly connected to fires and deforestation. Reducing those emissions would go a long way in helping meet global climate goals.

For once, though, scientists, environmentalists and even neighboring nations are cautiously optimistic. For a country long known for environmental negligence, that alone is a success. Soon, Indonesians and those in neighboring nations might be able to breath easily, no matter how dry it is. ![]()

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!