April 17, 2013 — On a fast-moving stretch of the Mississippi River in downtown Minneapolis, a 9.2-megawatt hydroelectric dam generates enough electricity to power 7,500 homes. Built by Brookfield Renewable Energy Group and Nelson Energy, the Lower St. Anthony Hydroelectric Project sits in a lock of an existing U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dam.

The Lower St. Anthony is the first major new hydroelectric project on the upper Mississippi in decades. It represents a budding movement to begin tapping into the world’s most overlooked yet reliable power source — moving water. Although most of the rivers best suited for large hydropower plants already have seen the installation of massive dams and turbines that use the power of trapped water gradually let loose to generate electricity, what’s left is still a pretty rich trove of potential. Energy developers are now eyeing large and small river systems, tidal basins and even big western irrigation ditches as sources of a less common but very promising approach to tapping the power of water: small hydro.

Developers have focused on two broad types of small-hydro proposals: placing low-head hydro on existing locks and dams in rivers, and installing marine hydrokinetic turbines, which capture the energy of currents while being tethered to floors of rivers and tidal areas.

“We have a chance to squeeze some new energy out of little spots,” says Matthew Nocella, spokesman for the Washington, D.C.-based National Hydropower Association. “Folks working in this market say there is a lot of interest right now on the small hydro side.”

Only 2,500 or so of the existing dams in the U.S. use the energy in flowing water to turn turbines that create electricity, leaving at least 54,000 (some suggest the number may be 80,000) unpowered.

It’s a global trend. In collaboration with the United Nations, China created the International Center on Small Hydropower to gather data and promote small hydro, and is seen as a global leader in its development. The center’s February 2012 newsletter highlighted low-head projects in Peru, South Korea, Uganda, China, Scotland, Switzerland and Tanzania.

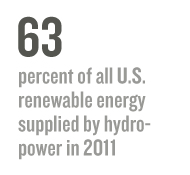

Like big hydropower, small hydro offers utilities the rarest of attributes among renewables: a steady stream of power day and night, unlike intermittent sources such as solar and wind. That trait is one of the reasons hydro supplies more than 90 percent of all electricity produced by renewable power sources, according to the World Energy Council.

A low-head hydropower facility installed on an existing dam in Minneapolis turns the power of the Mississippi River into electricity. Photo courtesy of Brookfield Renewable Energy Partners L.P.

Small hydro systems have additional advantages. They are seen as less disruptive and more widely applicable than conventional hydropower facilities because water dropping less than 30 feet can turn their turbines, and installation does not dramatically change a river’s flow or create pools of water.

“The idea is to create more distributed generation,” says Trey Taylor, co-founder of the marine hydrokinetic firm Verdant Power. “When you think about it, most people live near water, in some form or another.”

And there’s power in that water.

Lock and Dam Hydro

Only 2,500 or so of the existing dams in the U.S. use the energy in flowing water to turn turbines that create electricity, leaving at least 54,000 (some suggest the number may be 80,000) unpowered, according to an April 2012 report by the NHA and the U.S. Department of Energy. The vast majority of dams, in fact, are used for navigation, irrigation, municipal water supplies and flood control. The Army Corps’ National Inventory of Dams of 2007 shows half of those nonproducing dams are at least 25 feet tall. By simply adding a smaller version of conventional turbines to the dams with the greatest potential, as much as 12 gigawatts of capacity could be installed, an amount equivalent to roughly 10 to 12 nuclear plants, according to the NHA’s report. The International Energy Agency, meanwhile, reports only 19 percent of hydro’s potential has been tapped, much of which can only be unlocked with low-head hydro.

Low-head hydro operations have been around for decades, but the field is seeing a mild resurgence as improved technology makes capturing the power of moving water all that easier, as tax credits create opportunity and as interest in green energy grows. Filings from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which vets all U.S. hydro projects, reveal that nearly every Army Corps lock and dam in the country has a hydro project proposed on it, ranging from 5 MW to more than 100 MW. FERC has issued more than 1,000 licenses for new hydro projects since 2007, and several hundred sit in the pre-filing-phase queue. Applying and getting a license is just one step toward building a plant, but the numbers seem to indicate a renewal interest in hydro.

Low-head hydro operations have been around for decades, but the field is seeing a mild resurgence as improved technology makes capturing the power of moving water all that easier, as tax credits create opportunity and as interest in green energy grows. Filings from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which vets all U.S. hydro projects, reveal that nearly every Army Corps lock and dam in the country has a hydro project proposed on it, ranging from 5 MW to more than 100 MW. FERC has issued more than 1,000 licenses for new hydro projects since 2007, and several hundred sit in the pre-filing-phase queue. Applying and getting a license is just one step toward building a plant, but the numbers seem to indicate a renewal interest in hydro.

The agency even created an exemption from several aspects of the usual regulatory process for hydro of less than 5 MW. Jeff Wright, FERC’s energy projects office director, urged Congress last year to increase the exemption to 10 MW and to allow for a two-year, rather than three-year, application process.

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!