March 19, 2019 —  In a nameless spring on Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) in southeastern New Mexico, water bubbles up through dark sand and runs into a steep-banked channel en route to the Pecos River. The small pool it creates is clear and cold on a gusty, dry summer day, but it’s unremarkable, hidden by weeds. Yet its water, emerging from a deep aquifer, is coveted by people and animals alike, a critical resource for a nearby city, farmers and tiny endangered invertebrates.

In a nameless spring on Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) in southeastern New Mexico, water bubbles up through dark sand and runs into a steep-banked channel en route to the Pecos River. The small pool it creates is clear and cold on a gusty, dry summer day, but it’s unremarkable, hidden by weeds. Yet its water, emerging from a deep aquifer, is coveted by people and animals alike, a critical resource for a nearby city, farmers and tiny endangered invertebrates.

The Bitter Lake NWR isn’t alone in its ecological importance — it represents numerous spring-dependent ecosystems across the arid western United States. Encircled by rangeland, irrigated farms, and oil and gas development, they are often sanctuaries for species found nowhere else.

Springs from the desert Southwest to the oak savannas of Minnesota face common threats of groundwater pumping, contamination and climate change. Jeanette Howard, director of freshwater science for The Nature Conservancy’s California chapter, says the often-unique organisms that inhabit these springs rely on ancient waters, artesian aquifers that can be very slow to replenish. If the springs dry up, their ecosystems may never be restored.

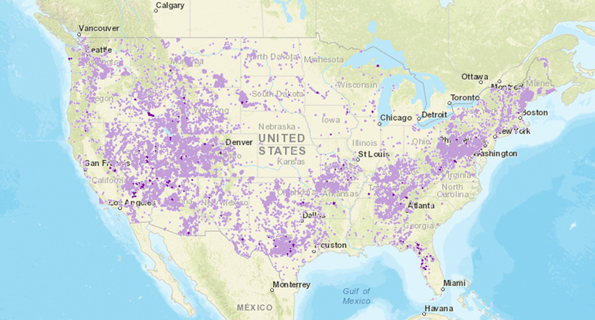

The U.S. is home to thousands of freshwater springs. Click on illustration to access an interactive map.

Not only that, but springs are a barometer for the health of aquifers that people rely on for everything from water in their homes to irrigation for crops. Stetson University biologist Kirsten Work, who studies fish and invertebrates in Florida’s numerous freshwater springs, calls them a “canary in the coal mine.”

“We need to care about springs because they tell us what our groundwater is like,” she says. “If the spring discharges decline, then we’re running out of groundwater and running out of drinking water.”

The Promise of Restoration

Bitter Lake NWR biologist Jeff Beauchamp says what makes the refuge special is its biodiversity. Located at the confluence of rivers and springs where shortgrass prairie meets the Chihuahuan desert, this oasis draws hundreds of species of birds, including the endangered least tern, and is home to two endangered fish, the Pecos gambusia and Pecos bluntnose shiner. Its habitats, which range from marshes to isolated sinkholes to muddy seeps, harbor a handful of endangered endemics: three snail species and a crustacean.

The Pecos gambusia (Gambusia nobilis) is one of two endangered fish found in Bitter Lake National Wildlife Refuge. Photo courtesy of Texas Parks & Wildlife Department © Dave Schlepper

Bitter Lake is one of their last refuges because changes in water quantity and quality have led to local extinction across their historic range of southeastern New Mexico and western Texas: Groundwater pumping, primarily for irrigation and household use, has led to springs drying across the region.

The Roswell aquifer, which feeds the Bitter Lake springs, also faces potential contamination as the Permian basin booms with oil and gas development. Bitter Lake’s greater “Habitat Protection Zone” hosts 20 active natural gas wells, and over 80 active oil and gas wells dot its aquifer’s source water area. Due to these threats, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently proposed upgrading the threat level of Bitter Lake’s endangered invertebrates to “moderate.”

To fulfill the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, refuge biologists keep close tabs on the invertebrates with semiannual monitoring. On a hot July morning they’re out surveying a small spring, sieving through algae and mud for snails the size of a sesame seed.

“They’re cute little critters,” says biologist Tim Huckaby, a Bitter Lake intern who’s using a microscope to distinguish two species. More importantly, he says, “They’re good indicators of water quality.” Huckaby says the snails clean the water by feeding on algae and microbes and seem to be sensitive to changes in water chemistry.

Today the team discovers hundreds of individuals of two species, a promising development for the snails, reintroduced here two years ago from a population in the main part of the refuge. This adjacent tract, on a reclaimed flood-irrigated farm, is thick with koshia, tumbleweed and other invasive weeds, with heavily incised ditches.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Bill Johnson describes major restoration at this spring site over the last decade. Muddy and channelized with cycles of flooding, “it never had time to develop with wetland plants.” After refuge managers worked to divert a river carrying contaminants from nearby Roswell and removed invasive species like carp and salt cedar, the wetland community around the spring flourished, becoming dense with salt and wigeon grasses. Johnson is pleased with a key discovery: snails found farther from the original translocation site than ever before. Now, as dragonflies zip over the clear, shallow water, Johnson says the spring looks “pretty good.”

Manatees Hold Sway

More than 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) away, Work says Florida’s water management districts aren’t adequately taking into account ecosystem impacts when planning for groundwater use. In Florida, 87 percent of the public-supply water comes from groundwater, one of the highest rates in the country. Work is worried that a recent building boom and increasing water withdrawals could have major impacts on Florida’s aquifer system.

Stetson University biologist Kirsten Work (second from left, handling the net), and students work to gather and catalog an invasive fish species in Florida’s Blue Spring State Park. Photo courtesy of Stetson University

When a colleague at a conference discussed spring-fed wetlands going dry in Texas, she realized others across the U.S. had similar concerns. What if they collaborated to study springs nationwide? Today, she envisions a national evaluation that would show the big picture beyond local, piecemeal objections to spring-harming water management plans.

There’s a disconnect between the reality of aquifer depletion and public perception, Work says. “Florida is so darn wet that people don’t see the issue.” While some conservation measures have been instituted, often it’s springs that are shortchanged under water management plans. In a recent analysis of 52 Florida springs, Work found that 51 had minimum flows, or water flow rates, set by management districts at levels below their historic means, some by 25 percent. “Maintaining discharge is critical to maintaining the integrity” of the ecosystems, she says.

One spring is an exception: Blue Spring State Park, a deep, limestone-floored spring fringed with cabbage palms and oak, and a critical warm-water refuge for threatened manatees. There, the local management district did set the minimum water flow at its historic mean, which Work credits to the presence of some 500 manatees, nearly 10 percent of the total manatee population in Florida.

“Manatees hold sway because they’re threatened and because people love them,” she says. “It’s hard to make an argument without manatees.” She hasn’t been successful in convincing people to protect springs for other animals. “You’re not going to get the public behind a little snail that’s the size of a piece of pepper.”

Work has begun scouring U.S. Geological Survey data from spring gauges and contacting scientists for the national evaluation she’s dubbed the “State of the Springs” report. She plans to finish the first stage on water quantity in the next year, in the hope it becomes a key resource to inform decisions by water managers.

The California Experiment

Howard says that in the environmental community, “we don’t spend a lot of time thinking about springs.” But she is hopeful about a new law she calls California’s “experiment.”

In 2014 California became the last state to enact statewide regulation of groundwater with its Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). Before the law, “you could do whatever you wanted” with water, says Melissa Rohde, Nature Conservancy groundwater scientist, as long as it was put to a “beneficial use” — for instance, to irrigate crops or provide water to homes. That led to a tragedy of the commons, Rohde says, with more than 95 percent of wetlands and riparian habitat, including spring-fed systems, lost, in part due to groundwater pumping.

The law establishes ecosystems as a beneficial use of water. SGMA is the first regulatory act in any state to require water agencies to consider impacts on groundwater-dependent ecosystems in their management plans.

But Rohde explains the law currently doesn’t extend protection to many of the most vulnerable ecosystems, including desert springs. The heavily overdrafted, high-priority groundwater basins covered by SGMA in its first round of regulations include just two deserts basins. “We’ve realized that 70 percent of our biodiversity exists outside of these basins,” she says, “So there’s a lot of ecosystems that are not being protected against potential impacts from pumping.”

Despite these drawbacks, Howard says the law is a model for other states and an important step towards protecting “both our aquifers and the faces of the aquifer, which are these groundwater-dependent ecosystems on the surface of the Earth.” She sees Work’s study as having the potential to highlight springs at the national level, similar to the visibility wetlands gained in the 1980s that helped lead to their protection. Springs are the lifeblood of many ecosystems, she says, and now people are finally recognizing their importance.

![]()

Related Posts

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!