May 20, 2015 —  Editor’s note: 2015 is shaping up to be a pivotal year with respect to climate change as growing concern about impacts converges with a critical stage in the decades-long process of shaping an international agreement to change our trajectory. To help us all prepare for the potentially game-changing 21st gathering of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 21) in Paris beginning Nov. 30, Ensia is publishing a series of context pieces from longtime observer and reporter Fiona Harvey. This second installment describes the fascinating, at times frustrating, at times fruitful trajectory that has brought us to this pivotal point today.

Editor’s note: 2015 is shaping up to be a pivotal year with respect to climate change as growing concern about impacts converges with a critical stage in the decades-long process of shaping an international agreement to change our trajectory. To help us all prepare for the potentially game-changing 21st gathering of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 21) in Paris beginning Nov. 30, Ensia is publishing a series of context pieces from longtime observer and reporter Fiona Harvey. This second installment describes the fascinating, at times frustrating, at times fruitful trajectory that has brought us to this pivotal point today.

For more than two decades, world governments have been meeting almost annually to try to forge a global agreement on reducing greenhouse gas emissions and staving off dangerous climate change. For all of that period, the negotiations have been hampered by the sheer complexity of what they are setting out to achieve: a fair agreement in which all nations, however strong or weak their economy, whatever the extent of their previous contributions of CO2, share the responsibility for reducing global emissions and preventing the worst ravages of global warming.

If progress seems slow, consider that these negotiations are among the last of their kind. World trade negotiations aimed at removing trade barriers among developed and developing countries, known as the “Doha round,” collapsed in 2008. Only a handful of global treaties have been negotiated in the past four decades, with most of these covering narrow issues and lacking strong incentives for countries to comply. Climate change, by contrast, is possibly the most intractable problem of our times, and solving it will require an unprecedented upheaval of the world economy to rebalance away from the fossil fuels which have been the engine of growth for more than a century and a half.

What has happened over these two decades? How have these past accomplishments, glacial as they seem, contributed to where we are today? And what does where we are today mean for the pivotal upcoming negotiations in Paris?

Prelude: Impact and IPCC

The science of global warming dates back to the 19th century, when thinkers such as Joseph Fourier and John Tyndall hypothesized that CO2 warms the atmosphere. At the end of the century, Svante Arrhenius made a series of calculations showing how far temperatures could rise or fall depending on the quantity of CO2 in the atmosphere. But this was considered arcane physical science until the mid-20th century.

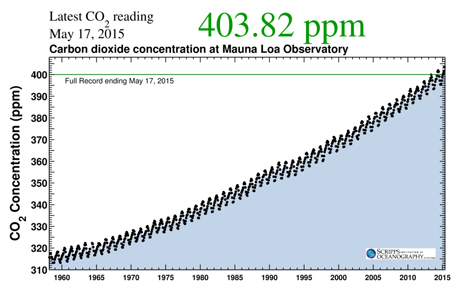

The Keeling Curve offers a striking look at the increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide over the past half century. Image courtesy of Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

In 1958, the chemist Charles David Keeling began measuring CO2 in samples of air at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii. The resulting graph showed variations within each year — highest during winter, then falling back as vegetation rejuvenates — but also, crucially, established beyond doubt that industrialization was adding to the stock of CO2 in the atmosphere each year.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, the Keeling Curve was joined by new studies from deep sea cores, tree rings and ice cores that added knowledge of past climate changes and CO2 fluctuations. These strengthened the connection between atmospheric CO2 concentration and global climate and led to growing concern that we could be changing the climate ourselves.

By 1988, enough evidence for a possible impact had accumulated that the World Meteorological Organisation and the United Nations cooperatively commissioned a comprehensive assessment intended to definitively establish whether humans could be changing the climate. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a group of the world’s leading climate experts convened by the U.N., published a report in 1990 concluding that human-caused release of gases such as CO2, methane and nitrous oxide were enhancing the natural greenhouse effect.

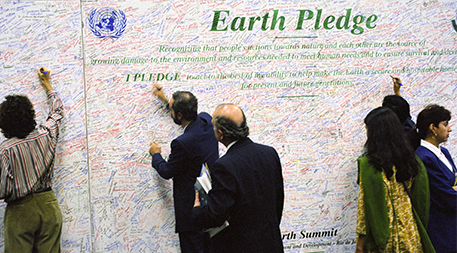

Participants in the 1992 Rio Earth Summit sign a pledge to “help make the Earth a secure and hospitable home for present and future generations.” Photo © UN Photo/Tom Prendergast.

In 1992 these developments led to a global conference around climate change, the U.N. Conference on Environment and Development (aka Earth Summit), in Rio de Janeiro. At the summit, world leaders, including George H.W. Bush, signed the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, indicating their commitment to avoiding dangerous climate change. Signatories to the UNFCCC agreed to meet regularly in a conference of the parties — COP — to discuss implementation of the treaty.

But the UNFCCC had a crucial flaw: There was nothing in it to commit signatories to specific actions. As a result, additional negotiations were scheduled to set out rights and responsibilities for each country. That’s where the trouble really began.

Kyoto 1997: Legally Binding, Practically Useless

The issues to be addressed by further negotiations were huge. One was advancing the science, with the aim of gaining further clarity on how human activities were affecting climate and what measures would be needed to stave off these effects.

Poor countries were adamant that their economic development should come first.But that was the easy part. The politics and the economics — with business groups beginning to wake up to the threat that tackling emissions could pose to their interests — were far more challenging.

Poor countries were adamant that their economic development should come first, and demanded the right to develop along the same paths rich nations had taken before them. (Although some, including China and India, were lifting millions of people out of poverty and rapidly industrializing, their emissions per person were still well below those of the West.) They also argued that, because developed countries were responsible for most of the human-generated CO2 in the atmosphere, those countries should bear the greatest responsibility for reducing it. This included not just taking on emissions cuts while poor nations continued to increase their own emissions, but also providing financial assistance to the developing world to help those countries cut emissions and cope with the effects of warming.

Russia, meanwhile, along with many of its former satellite states, was suffering deep economic malaise after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Its greenhouse gas emissions had slumped in tandem with its industry.

While some in rich countries were sympathetic to the developing world’s concerns, and the collapse of Russia appeared to take out a major political and economic competitor, there was resistance from many to the idea that they should shoulder the whole responsibility while rapidly expanding economies such as China bore none. The impact of low-cost competition from Asia was beginning to be felt, and there were fears that China was exploiting global warming to gain a further economic advantage over the West.

These arguments formed the background to an Earth Summit follow-up meeting in Kyoto, Japan, in 1997. The agreement that emerged, the Kyoto Protocol, divided nations into two groups: those accepting limits on their emissions (the developed world, including the U.S., the European Union, Japan and most of the post-Soviet bloc), and those without targets (the so-called non-Annex 1 countries, including China, India and other rapidly growing economies such as South Korea). Altogether, the Annex 1 countries were expected to reduce their emissions of six greenhouse gases by about 5.2 percent from 1990 levels by 2012 — though some were allocated targets allowing a small increase in emissions instead.

The Kyoto meeting also established a mechanism for a global system of emissions trading whereby rich countries with emissions targets could avoid reducing their own carbon output by paying developing countries to adopt strategies, such as planting trees or installing solar or wind power, that reduced greenhouse gases there instead.

Then–U.K. environment minister John Prescott, who led the negotiations on behalf of the European Union, recalls leaving the negotiating room in the early hours wreathed in smiles after hours of tense negotiations, hugging bystanders on his exit, in joy and relief. “It was a great moment!” he remembers.

But the joy was short-lived. Though the U.S., represented by Vice President Al Gore, signed the protocol, it was never put before Congress for ratification because it was clear that it would not pass because some thought it appeared to give China a free pass and some business interests were gearing up to oppose the agreement (including by casting doubt on the science of climate change). Russia also determined not to ratify the pact. Kyoto could not legally come into effect unless countries responsible for 55 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions ratified it. Without the U.S., the world’s biggest emitter, that looked scarcely possible.

Lesson learned: A treaty can be legally binding, fully articulated, elegantly written and watertight under international law — and still be of no use.The Kyoto protocol was a fully legally binding document, signed by nearly every government in the world. But it ended up having little practical effect on emissions, which continued to rise, or on finance, as developing countries received only small flows of funds. Meanwhile, its effect on politics was negative, because it cast doubt on the ability of the U.N. negotiating process to produce a meaningful deal.

Lesson learned: A treaty can be legally binding, fully articulated, elegantly written and watertight under international law — and still be of no use, if the politicians of the day do not support it.

Post-Kyoto: Off the Table

After the Kyoto protocol was signed, climate negotiations entered a period of “phony war.” Countries continued to meet — for instance, establishing in 2001 the Marrakech Accords, by which key aspects of the Kyoto Protocol were elaborated on — but the effort was largely futile. The Clinton administration was powerless to revive Kyoto. And George W. Bush made it clear soon after he took office that — despite some words during his campaign on the need to tackle global warming — U.S. participation in international climate action under the auspices of the U.N. was off the table.

The stalemate carried on for some years. Then, unexpectedly, in late 2004 Russia ratified the treaty — prompted by Vladimir Putin’s desire to join the World Trade Organisation and his strategy to gain the support of the EU using Kyoto as a quid pro quo. That move rescued Kyoto from the dust heap of history and started a new phase of negotiations.

Bali 2007: Breaking the Barrier

Yvo de Boer, a European bureaucrat with previous knowledge of the climate talks, took over as executive secretary of the UNFCCC in 2006 and made it clear from the start that he wanted the U.N. secretary-general, Ban Ki-moon, to throw the full weight of the organization behind a push for a new global agreement on climate change. The first stage in this was to agree to a “road map” that would allow countries to move beyond the impasse that followed Kyoto — essentially, though this was not the official line, to pursue an alternative to Kyoto that would require limits to greenhouse gas emissions and apply to everyone, including countries that had rejected Kyoto and countries that had no obligations under the 1997 protocol.

U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (right) and UNFCCC executive secretary Yvo de Boer address a press conference at COP 13 in Bali. Photo © UN Photo/Evan Schneider.

This was agreed at COP 13 in Bali at the end of 2007, but not without drama. The conference was scheduled to end at 6 p.m. on Friday, Dec. 14, but the U.S. continued to reject the plan (on the basis that it was a “one-size-fits-all” solution, rather than one honed to individual countries’ needs) into the following afternoon. In the tense final hours, as it looked as if no agreement could be reached, de Boer appeared to break down in tears on the podium, while representatives of developing nations stood up in turn to denounce the U.S. position. An impassioned plea from Papua New Guinea to “lead [or] get out of the way” was the final straw. The U.S. delegation agreed to the road map, amidst scenes of relief and jubilation.

Copenhagen 2009: Short of Goal

The Bali road map paved the way for a crunch summit on climate change — a meeting of world leaders in Copenhagen in late 2009, at which it was expected a successor to the Kyoto protocol would be forged. The Copenhagen meeting was unique in that it was not only a COP (COP 15), but also a summit — meaning that delegations were led by heads of state, rather than ministerial level representatives. In the run-up to the talks, the omens were good: The EU and most developed countries were behind a deal, while in the U.S. the new president, Barack Obama, vowed to resume international action on climate. China’s government also encouraged a deal, and other developing countries were willing to follow suit.

In advance of the summit, China, India, the U.S., the EU, Japan and all of the world’s other biggest economies declared targets for greenhouse gas emissions for 2020. It was the first time that developed and developing economies had jointly agreed on carbon targets (absolute cuts for richer nations, curbs to the likely growth of future emissions for developing countries).

But by a few months before the conference, it was clear that, despite the willingness of all the major parties to sign a deal, there would be no treaty emerging from Copenhagen. There was not enough time (deadlines are key to getting any outcomes at all in these negotiations) to put together a fully articulated and legally binding agreement of the kind agreed in Rio and Kyoto. Instead, the UN decided to seek a “political declaration” signed by world leaders.

NGOs and media branded the summit a failure. Still, it marked the first time that developed and developing countries had come together with targets on emissions — targets that were a strong advance on those of Kyoto. Also, financial assistance from the rich to the poor world was agreed upon at levels far higher than ever.

Connie Hedegaard, host and president of COP 15 in Copenhagen, briefs correspondents on the 2009 negotiations. Photo © UN Photo/Eskinder Debebe.

Post-Copenhagen: Growing Hope

The scenes of chaos and the bitter recriminations among countries and with non-governmental organizations at the Copenhagen summit deeply damaged the public perception of the UN talks, which have been increasingly vulnerable to attack since then.

Nevertheless, the tables began to turn a bit in 2010, when the U.N. formally adopted the Copenhagen agreement at COP 16 in Cancun.

Connie Hedegaard, the Danish environment minister for the Copenhagen talks as well as a politician and former journalist, had hosted and presided over the 2009 summit at no little personal cost — she suffered pneumonia in the immediate aftermath. When she was appointed the EU’s commissioner for climate action in 2010, she was determined to use the post to ensure that Copenhagen was just a first step to global agreement, not a final one.

At COP 17, held in 2011 in Durban, South Africa, Hedegaard made her big gamble. While other delegations turned up expecting another “holding” conference at which little would be agreed other than to keep talking, the EU came with a plan: to force a deal on post-2020 targets. That would mean countries agreeing to a timetable for a global pact to be signed in 2015, and coming up with far more ambitious climate goals than they had produced just two years earlier.

It was a risky move, and it very nearly failed. As the talks continued beyond their Friday 6 p.m. deadline, into the following morning and the next afternoon, with no resolution in sight, key developed country delegations such as the U.S. and Japan were still not on board with the EU. But many developing countries were: Hedegaard had managed to forge a coalition with more than 100 of the poorest nations, persuading them that a new post-2020 agreement was in their favor because they had most to lose from the ravages of climate change. Exhausted delegates proposed postponing the talks for three months. Hedegaard knew resolution could not be delayed, however, if the fragile coalition she had assembled were to prevail.

In the end, shortly before dawn on Sunday morning, after a marathon 40-hour-plus negotiating session, Hedegaard’s gamble paid off. China and India were the last nations to hold out against the proposals. Painted as preventing poorer countries from gaining the results they judged to be in their best interests, the two finally gave in, and a timetable was put into place that should require a new global agreement to be signed in Paris in 2015, coming into force from 2020, and binding developed countries to further emissions cuts and developing countries to curb the growth of their carbon output. But the terms of such an agreement were deliberately kept vague, allowing for a “protocol, legal instrument or other outcome with legal force,” which at its worst could mean that all countries were not bound to carry out the agreement. The meaning of this clause, inserted at the last minute, is likely to be a key cause of contention in Paris.

Paris 2015: Crucial Ingredients

Durban set the scene for COP 21, planned for Paris this coming November. At COP 20 in Lima in late 2014, much of the text for a Paris agreement was laid out. But two crucial things were left out of the Lima text: the post-2020 targets on emissions proposed by each country; and the financial assistance that developed countries will agree to provide to the developing world. The national post-2020 plans were supposed to be submitted by the end of March. So far, more than 30 countries — most of them EU states — have set out their national plans on emissions. The U.S. has agreed to a cut of up to 28 percent from 2005 levels (the same baseline as it used for Copenhagen) by 2025, while China has said its emissions will peak by 2030. Work is ongoing on financial commitments, but this is likely to be a continuing source of contention up to the final days.

Whatever the outcome in Paris, one thing is certain: it will not be a final resolution to the problem of climate change. The bigger picture driving all this activity has also changed. Research published by the Global Carbon Project in 2014 showed that China’s emissions per capita had exceeded those of the EU, while India’s total emissions are likely to surpass Europe’s by the end of this decade. In the same year, the IPCC published the full findings of its latest assessment report, which concluded that about half the amount of fossil fuel that can be burned before we are likely to surpass the 3.6 °F (2 °C) of warming threshold had already been burned.

Next Stop: Real Reductions?

Whatever the outcome in Paris, one thing is certain: it will not be a final resolution to the problem of climate change. Governments will need to continue meeting, year after year, to ensure that efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are on track and to ratchet up their commitments.

Though the UNFCCC process can seem tortuous — nothing can be passed unless it has unanimous backing, the talks are split into dozens of working groups and the arguments over seemingly simple matters of wording are frequently excruciating — this is still the only forum in which every country has equal weight, the only one in which most developing countries are heard. That confers on this process a legitimacy that is lacking in forums posited as alternatives.

The post-Paris process promises to be just as fraught as the previous 20 years of talks. The key to any judgment will be whether these ongoing discussions yield real reductions in CO2, or just more hot air.

![]()

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!