September 16, 2013 — Religious groups are the original conservationists. Worldwide, spiritual organizations own 5 to 10 percent of forests, and sacred sites occur on every continent except Antarctica. An estimated 70 percent of national parks that exist today were originally preserved by spiritual groups, and some sacred sites in Mongolia and China have been quietly protected for more than 1,000 years.

This all makes perfect sense to Martin Palmer, secretary general of the Alliance of Religions and Conservation. “Manifestations of the divine do not take place in car parks or on the top of high rises, but on mountains, in deserts and by rivers,” he says. “We relax more when we’re in nature rather than striding through a city, and when we relax perhaps we’re more capable of believing we just heard the voice of God.”

Yet, until relatively recently, few conservationists were aware of these holy havens for habitat.

Shonil Bhagwat, an environmental geographer at the Open University and senior research associate at the University of Oxford, stumbled upon this phenomenon by chance. As a teen growing up in India, he would frequently roam the foothills of the Western Ghats Mountains. “During my journeys there, I often came across peculiar forests,” he recalls. “There would be a little shrine in the middle of the forest, but for no obvious reason.”

Intrigued, he began inquiring about the shrines to any passersby he encountered during his long walks. “I started to discover the religious and spiritual importance these forests had to people,” he says.

Science and religion have long suffered an uneasy relationship, and environmental science is no exception. Despite the value both conservation and religion place on nature, tension often divides the two.

Their origins, he found, predate contemporary Hinduism, reaching back to animistic traditions — the belief that animals, plants, landscapes and natural objects contain a spiritual force. Elements of animism still often blend into formal religious doctrines and some modern-day modes of worship, including Hinduism, Buddhism and Shintoism, continue to look directly to nature for inspiration and guidance. Over the past 1,500 years, in the forests Bhagwat roamed as a youth, statues of the old nature gods were gradually adopted as representations of Shiva, Lord Ganesha or other mainstream deities. “There was a handover between one religious tradition to another, even though the site remains the same,” he says.

After receiving a scholarship to attend Oxford University in 1997, Bhagwat decided to pursue a formal study of his homeland’s sacred forests. Many of those forests, he knew, only existed as a few stands of trees here or there — the kind of patchy habitats that conservationists normally dismiss as “living dead forests” that no longer support significant biodiversity.

When he looked closer, however, a different picture emerged. Viewed at the landscape level, the numerous sites — which some estimates place around 150,000 — create a loosely connected network of scattered forest patches across the Indian countryside. “Taken together, these forests have a much stronger presence on the landscape than afforded by any individual patch alone,” he says.

They also provide protection for endangered habitats. In southwestern India, for example, most protected areas occur on mountains since those steep sites are useless for agriculture or development. All other landscapes in the region — marshes, swamps, forests — escape the umbrella of conventional conservation, placing those low-lying areas in jeopardy. That’s where the sacred sites come into play, Bhagwat learned, many of which harbor unique species. “While analyzing my data, I came across fascinating patterns of biodiversity of trees, mushrooms and a variety of creatures,” he says. “For example, in the coastal parts of South India, the nutmeg tree is only found in sacred groves, which are really the last stronghold of this particular species.”

Encouraged, Bhagwat began searching for similar examples beyond India. He soon learned, however, that very little scientific literature existed on the wider topic of sacred landscapes. This brought him to Palmer, who has worked for the past three decades to bridge the spiritual and scientific in unified pursuit of conservation by systematically demonstrating what one group can offer the other, and by bringing leaders from both parties together in dialogue. “In order for us to be able to argue the case that a sacred landscape is significant, we need information and data,” Palmer says.

False Dichotomy

Getting scientists involved, however, is not always easy. Science and religion have long suffered an uneasy relationship, and environmental science is no exception. Despite the value both conservation and religion place on nature, tension often divides the two.

In the late 1980s, Palmer started organizing meetings between environmental organizations and spiritual leaders, but found conservationists often feared that partnering with religious organizations would undermine their credibility as scientists. Politics, especially in the U.S., came into play, with liberal environmentalists often equating religion to conservative thinking, and vice versa. Voices of reason supporting a greater dialogue between science and religion, such as that of acclaimed biologist E.O. Wilson, were largely drowned out amidst the bickering, Palmer says.

“While [China’s] cultural revolution seriously damaged natural sites, those which were sacred were better protected because local people held them in such awe and respect.” – Martin Palmer

“I think there is sort of a block in communication,” Bhagwat adds.

Breaking through that communication block, Bhagwat and Palmer say, can only benefit conservation. When governments collapse and policies change, national parks are often taken with them. But sacred sites tend to remain static throughout time.

“While [China’s] cultural revolution seriously damaged natural sites, those which were sacred were better protected because local people held them in such awe and respect,” Palmer says. Likewise, during the Iranian revolution the national park regime was quickly dismantled, but sites that held religious value survived. “I think we have a rather idealistic notion that what we create as nations or international bodies will be respected, but the evidence doesn’t show that,” Palmer says. “Religion outlives dynasties, empires, ideologies and regimes, and has been protecting the sacred for a very long time.”

In 1997, Palmer began working with the World Wildlife Fund, the International Union for Conservation of Nature and UNESCO to formally recognize the term “sacred natural site.” Thanks to those efforts, the term entered the conservation nomenclature, which Palmer considers a major achievement for gaining recognition of religion’s important role in conservation.

“I’d say we still have a long way to go to bring about change in perception, attitudes and behaviors, but it’s slowly happening,” Bhagwat says.

Breaking Bread

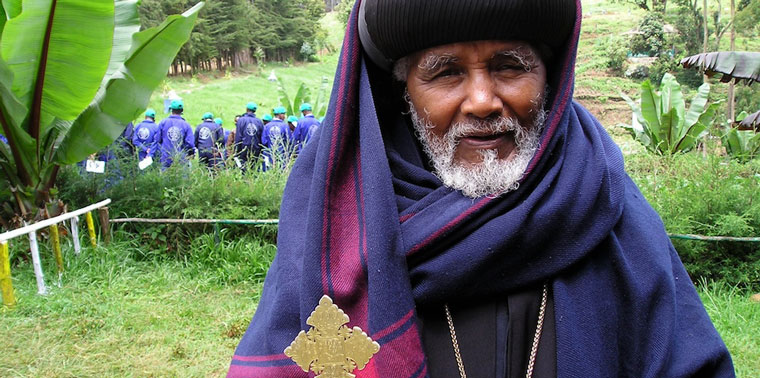

Thanks to Palmer, Bhagwat and others, more researchers are recognizing sacred landscapes as valuable study sites. Ashley Massey, a doctoral candidate working with Bhagwat, conducts research in Ethiopia, where thousands of Orthodox Tewahido Church forests represent the last remaining fragments of the country’s once-expansive Afromontane woodlands. The forests, which each cover an average of 6 hectares, act as seed banks and provide habitat for plant and animal species otherwise stamped out in the agricultural surroundings. In a preliminary analysis of 1,173 church forests and their local bee species, Massey revealed that the forests support pollination zones spanning more than 300,000 hectares in croplands. Empirical studies have found up to a 40 percent boost in crop yields thanks to pollination by bees and other insects found in these forests. With these data, Massey hopes that the church forests will attract international support and the Ethiopian government will update its environmental policies to incorporate protection of important areas for pollination.

View the Sacred Oases photo gallery

A continent away, in Tibet, “love all life” is a basic tenet of the predominantly Buddhist population. Buddhist monks there play a direct role in upholding this rule by patrolling the lands surrounding their monasteries and teaching the approximately 76,000 people living in the area the importance of respecting nature. Li Juan, a postdoctoral researcher at Peking University, surveyed a quarter of all Tibetan monasteries in the Sanjiangyuan region in Qinghai Province to quantify the influence they have on the environment. When she interviewed 144 local herders and asked them why they chose not to kill wildlife, 42 percent told her because it is a sin according to Tibetan Buddhism.

Li also found that around 90 percent of the monasteries fall within a 5-kilometer range of endangered snow leopard habitat. While around 1.5 million square kilometers of snow leopard habitat in the area are designated as an official nature reserve, only three park staff are currently employed to patrol one 42,000-square-kilometer section of that reserve. On the other hand, there are 336 monasteries scattered throughout the landscape. “It takes the [nature reserve] staff about 60 days to patrol the area just once, so the monks are more productive,” Li says.

“Many indigenous groups and people whose forests are not recognized locally by the country or state told us that they want those places mapped.” – Ashley Massey

Sacred sites also sprout up in some urban areas alongside skyscrapers and sprawl. Japanese citizens tend to around 58,000 Shinto shrine forests, which often provide residents with their only connection to the natural world. The shrines are positively correlated with how happy people report being. The Eyup Sultan Mosque in Istanbul provides the last remaining breeding grounds for storks in the heart of a city of 13 million. And in Tokyo, which Palmer describes as “one of the least sympathetic cities for nature that you can imagine,” the royal palace’s sacred grounds preserve remnants of Tokyo’s indigenous organisms, including snails, frogs and native plants.

To keep up with and bring attention to such sacred landscapes, Bhagwat, Massey, Palmer and colleagues created an aggregate database in the form of an interactive, open-source map. The project, Mapping the Sacred, aims to engage indigenous communities and religious groups around the world in representing their own sacred traditions. The researchers have entered geo-referenced data for around 80,000 Shinto shrines in Japan, 550 Ethiopian church forests and 150 Indian sacred groves. Once some kinks are worked out, the project’s coordinators expect users around the world will be able to add their own sites to the database, probably sometime in the fall of 2013. “Many indigenous groups and people whose forests are not recognized locally by the country or state told us that they want those places mapped,” Massey says. “They would like to have the credit and international recognition for the forests they manage.”

Spirituality Among the Secular

Indifference rather than opposition to the sacred, Palmer thinks, is more dangerous for undermining it. Soviet communism, for example, actively sought to stamp out spirituality. When that regime fell, sacred sites in Kazakhstan, Mongolia and Russia quickly regained their status. In North America and Europe, on the other hand, Palmer fears that sacred landscapes may be lost simply because they are dismissed or forgotten.

Cemeteries are an exception, though, considered as they are in the West hallowed sites for the religious and secular alike. Because cemeteries are often located in expansive grassy or wooded plots free from the threat of major development, they can provide a refuge for plants and animals. In the United States, the Calvary Cemetery, just north of downtown St. Louis, Mo., contains the last true prairie remnants anywhere in the metropolitan area. Erin Shank, an urban wildlife biologist with the Missouri Department of Conservation, is working with the cemetery and other partners to restore and preserve those 25 acres using traditional methods such as prescribed fire. Seeds collected from the site’s rich diversity of native grass species also help to build new prairie plots around St. Louis. Shank says that the cemetery setting helps lend a sense that she’s dedicating her work to “something significant.”

“Oftentimes we don’t do conservation for some immediate benefit but because we truly believe in the long-term benefit, not just for the human community but for other life forms that depend on that habitat to survive,” she says. “This is something that I hope I can look to as an accomplishment of my life’s work, something that will be there beyond my lifetime or my children’s lifetime.”

Occasionally, rare species turn up alongside the graves, too. The Jacksonville cemetery in southwestern Oregon provides habitat for the threatened Gentner’s fritillary, a showy lily distinguished by its yellow and burgundy checkerboard petals. The small-town citizens have adopted Gentner’s fritillary as their unofficial symbol, and hold a festival in the flower’s honor each year in late March and early April. The lily likely thrives there due to the unique landscape the cemetery provides. Graves dating back to Oregon’s pioneer days are nestled amid remnants of a once-abundant habitat type, the ecotone between oak woodlands and meadow. “This habitat has been degraded due to changes in land management and exposure to competition from nonnative invasive weeds,” says Jordan Brown, a conservation biologist and botanist at the Oregon Department of Agriculture’s Native Plant Conservation Program. Brown and his colleagues manage the few sites where Gentner’s fritillary grows, weeding out invasive species, mapping the location of the rare plants and augmenting wild populations with specimens grown in their facilities.

“In a way, these rare species are a relic of a bygone era when diversity was once much more prevalent across the landscape,” Brown says. “They’re a reminder that we should feel obligated to respect the history and life that came before us.”

In the U.S. and Europe, hallowed sites often assume a deeply personal rather than community-based significance, Bhagwat says. He gives the example of a citizen who does not consider himself religious and yet harbors fond memories of visiting a lakeside with his grandparents as a boy. To him, that lake may be sacred, and he would likely oppose a condominium or golf course being built around it. That man may represent just one voice of opposition to development, Bhagwat points out, but what if there were hundreds of people who shared some personal connection to that same shore?

If the idea of individual and community sacredness is included in conservation discussions, Bhagwat thinks, it would create an even more compelling map. He is already thinking ahead about ways to incorporate this nuance into the Mapping the Sacred project. “I think a platform like this would really be an opportunity to express the links between humans and nature,” he says. “I think somewhere deep down, we all have a spiritual connection to nature.”

![]()

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!