April 23, 2013 — One rainy day in May, during his 10th trip to Kenya in seven years, Greg Allgood stood at the edge of a shallow pond on the outskirts of Mombasa and watched as a dozen schoolchildren scooped water from a shallow pond. The water, which had been deposited from recent rains, was thick with claylike dirt and bacteria-laden ground runoff. Were it to be poured into a glass, many American children would have thought it chocolate milk. But for these Kenyan children and their families, the filthy and potentially deadly liquid was their only source of drinking water.

“In many parts of the developing world, people are drinking from water that’s so bad I wouldn’t want to walk barefoot in it for fear of getting diseases,” says Allgood, director of the nonprofit Children’s Safe Drinking Water program at Procter & Gamble. “It’s a huge global problem — there are more than 1 billion people around the world who do not have access to clean, safe drinking water.”

P&G has provided more than 5 billion liters of clean, safe drinking water to people who desperately need it.

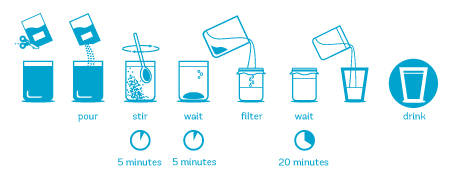

Back at the village school, Allgood poured the brown pond water into buckets while the kids added packets of white powder called “P&G Purifier of Water” (formerly PUR). After slow stirring, the water began to turn clear and the dirt and goop dropped to the bottom. As the children stared in amazement, Allgood filtered the water through cloths, waited 20 minutes and then took several gulps. The children eagerly drank the rest.

Allgood has performed this demonstration in some 20 developing countries. Through his efforts, P&G has provided more than 5 billion liters of clean, safe drinking water to people who desperately need it.

Keith Kall, a senior director for global corporate partnerships with the Christian relief organization World Vision, says P&G’s impact on the global problem of drinking water has been enormous.

“When you’ve got close to 2 million children dying every year due to diarrheal diseases, most of it from bad water, [P&G Purifier of Water] has helped save thousands of lives,” says Kall.

P&G Children’s Safe Drinking Water program, which Allgood spearheaded more than eight years ago, provides the packets at cost — 3.5 cents each — to a network of humanitarian organizations. The groups then sell them to those in need for roughly 7 cents each, with the difference going to cover transportation and import duty costs, as well as to educate people on how to use the product. In response to disasters like the 2010 floods in Pakistan and earthquake in Chile, P&G has provided water purification packets for free.

Although the Children’s Safe Drinking Water program is P&G’s leading philanthropy initiative, the effort originated not as charity but a product launch gone awry. In 2002, the consumer products giant started selling its new water purification technology in Guatemala, followed by Morocco, the Philippines and Pakistan. The product was envisioned as a way to reach customers at what’s often referred to as the bottom of the pyramid — the poorest of the poor who don’t have much in the way of spending power but who represent a potential market of more than a billion people. After a year and a half, P&G found itself losing money because it lacked the infrastructure to distribute the packets and to educate people on how to use them.

Recognizing that the program was on the verge of being disbanded or sold, Allgood lobbied for its survival as a nonprofit. It wasn’t an easy sell.

“We had had a team of 30 people in the company working on [P&G Purifier of Water] and had invested $10 million in test markets, and still we failed,” recalls Allgood, whose background is in toxicology and public health. “So then you have someone who’s not a sales guy saying he wants to run it as a not for profit. Some people were flat against it.”

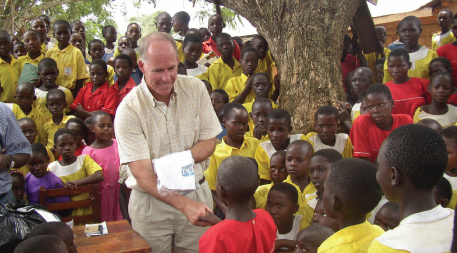

Greg Allgood meets with students who have been given informational pamphlets about P&G’s water purification packets and asked to do demonstrations at home for their parents. Photo courtesy of P&G Children’s Safe Drinking Water.

Allgood ultimately won over many of his critics and earned the support of then-CEO A.G. Lafley by arguing that the program would benefit not just poor families in the developing world, but P&G as well. By taking the lead in addressing one of the world’s biggest health problems, the company would, Allgood contended, gain a reputation as a good corporate citizen. It would also motivate and inspire employees, lending weight to the idea that P&G doesn’t just sell bottles of hair conditioner and shaving cream, but actually improves people’s lives.

“I get emails all the time from employees that have literally joined P&G because we do this,” says Allgood. “They may be going to work on Old Spice, but they say it was the deciding factor in where they decided to work.”

![]()

A version of this article originally appeared in the Fall 2010 issue of Momentum magazine, Ensia’s predecessor, with the title “Pure Genius.”

Ensia shares solutions-focused stories free of charge through our online magazine and partner media. That means audiences around the world have ready access to stories that can — and do — help them shape a better future. If you value our work, please show your support today.

Yes, I'll support Ensia!